Principles of PD: The Profession and Craft of Public Diplomacy

"Metaphors give words a way to go beyond their own meaning. They are handles on the door of what we can know and of what we can imagine. Each door leads to some new house and some new world that only that one handle can open.

What’s amazing is this: By making a handle, you can make a world."

—Jane Hirschfield, "The Art of the Metaphor"

The previous chapters outline the structural, environmental, policy, and strategic context for the conduct of public diplomacy in the United States. These foundational concepts demonstrate the depth of knowledge that underpins the work that public diplomacy practitioners are engaged in day-to-day. While the label “public diplomacy” may be relatively new, the significance and relationships between power, statecraft, diplomacy, information, networks, communication, interests, strategy, policy and tactics are not. While technologies and communication channels change, policies and regulations change, and priorities and programs change, many of the core ideas that inform the logic and principles of public diplomacy have remained consistent. Public diplomacy advances U.S. strategic priorities and foreign policy goals by engaging with selected foreign public audiences through deliberate planning and implementation of interventions that include programs, messages, campaigns, initiatives, events, and activities.

Still, as with any human endeavor, there is gray area, change, and ambiguity. In the practice of public diplomacy, the United States relies on the professionalism and judgment

of expert practitioners. Public diplomacy practitioners are professionals who operate at the nexus of two key instruments of statecraft and national power: diplomacy and information. Viewing PD as a profession enables us to take seriously the idea of developing a collective identity, embracing the importance of continuing education and training, and identifying a body of expert knowledge that PD practitioners share.

In outlining the contours of the professional body of expertise and identity, some guiding questions are instructive:

● What mental models or frameworks are available to describe the conduct of the modern, professional practice of public diplomacy?

● What are the core values that PD practitioners embrace as part of their professional identity?

● How do PD practitioners balance the inherently interpersonal and creative elements of their work with the requirements of modern PD being policy-centered,

audience-focused, and data-informed?

A. The PD Framework

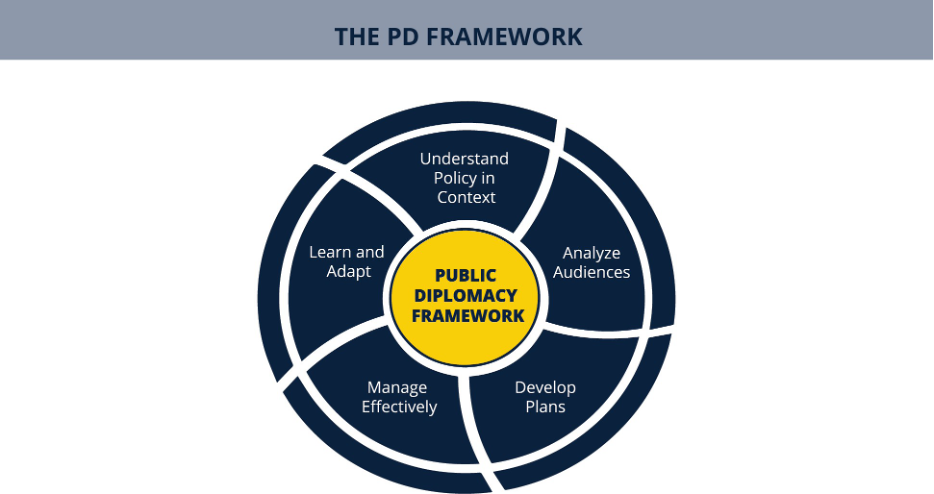

The Public Diplomacy Framework (PD Framework) articulates five elements to describe the conduct of modern, professional public diplomacy work.52 The PD Framework is a mental model to guide the practice of modern, professional public diplomacy. Modern PD is adaptive, policy-centered, audience-focused, data-informed, and designed to deliver demonstrable foreign policy outcomes. The PD Framework guides the effective use of the Department’s PD resources in advancing U.S. foreign policy priorities.

Figure 6. The elements of the PD Framework illustrates how the framework elements support, PD practitioners' efforts to align PD efforts with strategic goals.

A graphic representation of the PD Framework shows five equal elements in relation to each other and to the ultimate purpose of public diplomacy, which is to achieve U.S. foreign policy outcomes.

● Apply Policy in Context: Develop a comprehensive understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals and objectives in the relevant local context to determine the role public diplomacy plays in advancing specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

● Analyze Audiences: Identify specific audiences from among the key stakeholders on an issue and select audience segments whose attitudes behaviors, and beliefs are most likely to bring about the desired policy outcomes for PD initiatives and activities.

● Develop Plans: Create actionable plans tied to clear policy aims an measurable objectives to employ appropriate public diplomacy tactics with defined audiences to advance specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

● Manage Effectively: Set a common strategic vision to enable meaningful contributions from the full PD Section and other partners and allocate resources to efficiently and effectively implement and monitor public diplomacy initiatives and activities.

● Learn and Adapt: Monitor and assess whether public diplomacy initiatives

and activities are meeting their objectives, report on outcomes, analyze and share results, and use data to adjust plans and inform future efforts.

PD practitioners use the PD Framework to guide their strategic design, planning, management, measurement, evaluation, and adaptation of PD interventions to achieve policy goals and outcomes. Attending carefully to the five elements of the PD Framework enables PD professionals to operate and advocate effectively at the intersection of policy and public engagement.

The PD Framework promotes modern public diplomacy that:

● is designed to achieve both broad strategic goals and concrete policy outcomes;

● is planned, implemented, and assessed in a logical, transparent manner based on data and evidence;

● incorporates rigorous principles and pragmatic approaches to principles and approaches to monitoring, evaluation, and learning; and produces measurable outcomes for policymakers and the American public.

Public diplomacy, then, achieves desired foreign policy outcomes by understanding, informing, and influencing foreign public audiences and by expanding and strengthening the relationship between the people and government of the United States and citizens of the rest of the world. PD practitioners who actively and consistently apply the elements of the PD Framework in their work are better able to further U.S. foreign policy goals, advance U.S. interests and values, and strengthen U.S. national security by fully integrating public diplomacy work into that of the Department.

Importantly, the PD Framework is not a linear model, a process, or a cycle. Every part of the Framework is related to the other parts. For example, the element of Applying Policy in Context does not happen just once; PD practitioners should consider outcomes and audience consistently and alongside other elements of the Framework. Planning happens at multiple levels in concert with other sections in the mission as well as within smaller teams in the PD section. Effective management must happen at every stage of planning and implementation. Considerations about monitoring and evaluation must inform planning; learning and adaptation cannot simply happen at the end of a project or event.

The PD Framework offers a central mental model around which PD Practitioners can focus their personal professional and organizational development.

B. Core public diplomacy values

A key aspect of professional identity is having shared values. What values bind public diplomacy professionals together? Public diplomacy professionals are a diverse group, encompassing diverse employment types, job categories, education, training,

English-language skills, race and ethnicity, religion, citizenship, preferences, tech skills, and other characteristics. Defining core values rather than core job functions helps bind practitioners together in a common profession with a common goal.

Relationships and credibility are at the center of PD

Like all diplomacy, public diplomacy is relational and built on trust and respect between individuals and groups. Advancing policy aims requires careful cultivation of meaningful relationships with individuals and groups. Public diplomacy practitioners should not shy away from addressing difficult policy objectives or topics for fear that foreign public audiences are uninterested or disengaged in such matters. By addressing challenging and difficult policy objectives with humility and acknowledging the ongoing struggles in living our stated values, PD practitioners offer a dynamic counterpoint to alternative narratives, offer truths that are available for dialogue, and demonstrate what freedom of speech can and must look like in a democracy. This approach allows PD practitioners to be seen as honest brokers, which is crucial for advancing U.S. messages, interests, and values. It also means we must trust our audiences to understand U.S. values through our actions and not only our words. Public diplomacy professionals’ work must be credible and reliable, and it will be most successful when it is connected to policy that resonates positively with foreign public audiences. Everything we do communicates. Every program, action, image, and written or spoken word speaks for the United States, its government, and its people.

Modern PD requires a holistic, integrated approach to information and culture

Informing foreign public audiences through the use of traditional and digital media and public engagements is critical public diplomacy work. Responding to the day-to-day events and needs of the host country’s press, the front office, and other stakeholders is essential. Effective press and media work requires public diplomacy professionals to have respect and credibility with foreign press and media professionals. But this work alone does not constitute public diplomacy, which also involves advancing foreign policy objectives, building relationships, and shaping policy environments through in-person and digital engagement, experiential learning, exchanges, and other programs. Work with press and media should be integrated into the mission’s and PD section’s planning and programming. One of the core ideas of the Public Diplomacy Staffing Initiative (PDSI) is to break down silos that existed between the work of staff attending to press and media and those focused on engaging other audiences, primarily through cultural programs and exchanges. To successfully adopt an audience-focused approach that advances U.S. mission objectives, the Department must effectively integrate all functions of public diplomacy.

Public diplomacy can be measured, monitored, and evaluated

Public diplomacy seeks to advance U.S. foreign policy goals through understanding, informing, influencing, and building relationships with foreign publics. Measuring the impact of public diplomacy, then, is vital to making the case that public diplomacy contributes constructively to this end. While the long-term outcomes for public diplomacy may take decades to manifest, it is important for public diplomacy practitioners to employ the practices of monitoring, evaluating, and reporting to assess the efficacy of public diplomacy programs in the short, medium, and long-terms. The goal of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is to understand what is working and what is not working as well as we hoped, so we can modify our planning and implementation accordingly. Should we devote more money and effort into a particular issue or approach? Should we change our tools, tactics, or strategy? In some cases, evaluation may help us determine whether our interventions had an impact on a particular U.S. foreign policy objective. Measuring PD outcomes can be difficult, especially in medium- and long-term time horizons when many confounding variables may obscure a specific PD effect. However, the benefits of rigorous evaluation far outweigh the difficulties, which can be overcome through careful planning.

PD is ultimately accountable to the American taxpayer

To maximize the contribution of public diplomacy to the achievement of foreign policy objectives, PD practitioners must account for the needs and preferences of foreign audiences. However, they must also keep in mind that U.S. foreign policy objectives determine the focus of engagement with foreign audiences and not the other way around; public diplomacy is accountable to the U.S. taxpayer, not to the collective global good.

Although its approach to audience engagement bears a certain resemblance to marketing activities in the private sector, public diplomacy as a function of the U.S. government cannot be as solicitous or as responsive to audience interests. Public diplomacy, unlike commercial marketing, pursues audience engagement in the service of foreign policy, not to maximize market share or as an end in itself. In pursuit of outcomes that are qualitative rather than quantitative, the identity and influence of the audience for public diplomacy is also far more important than its size or scope. The U.S. government does not employ public diplomacy to engage large audiences but instead to serve its citizens through the furtherance of foreign policy.

Modern PD produces splashes, ripples, and waves

One common way of thinking about the effects of public diplomacy is to consider splashes, ripples, and waves, or short- medium- and long-term effects. In each instance, we make causal predictions: if we do x, then y will happen. We take specific actions to produce desired effects or outcomes in the world. We strive to apply public diplomacy according to causal logic with the expectation that it will produce the outcome we intended and predicted. However, we cannot control all or even most variables in the complex real-world environment in which public diplomacy operates. These intervening variables and changing circumstances obscure the mechanisms by which our actions have an effect, or not, the degree to which the effects comport with our expectations, and the time horizon over which they manifest.

In the short term, PD may aim to achieve specific effects: to correct misinformation, to convey a new U.S. policy, to encourage public support for a treaty. In the long term, public diplomacy is also about relationships shaping broad information and policy-making environments. PD can shape public opinion, sentiment, image, and affinity, which shape foreign actors’ decision-making space. Socio-political, economic, and cultural environments shape, constrain, and enable action. The United States believes its interests are served when more societies are free, open, prosperous, and democratic. These are environmental effects that PD seeks to achieve. Yet in the end public diplomacy is about more than maintaining a positive image of the United States; it is about achieving concrete and measurable U.S. foreign policy and national security objectives. Public diplomacy can and should help cultivate shared values and interests while contributing to cooperative, mutually-beneficial outcomes.

C. Complexity and tensions in PD

The practice of professions that require expertise, judgment, and choice require practitioners to hold competing positive ideas in tension. Diplomacy and the conduct of foreign policy are, after all, human endeavors. In the United States, public diplomacy situates itself between the U.S. government, foreign publics, and the American people. This intermediary position demands a sharp sense of cultural and interpersonal awareness and skill. Intermediaries with broad networks and deep relationships can facilitate dialogue and communication that might not otherwise occur. They can open up possibilities for diplomacy beyond traditional government-to-government communications. Professionals must become comfortable operating when the answer is “it depends,” and navigating when the environment is complex, ambiguous, with incomplete information. It requires an open mind and a willingness to take risks. This section presents a series of binary positions that—if wholly accepted—would ignore the nuance of public diplomacy as it is actually practiced. Some of the arguments are largely historical and others remain topics of discussion today, but all of them have some source in past thinking about PD and its role. Moving away from framing tensions as stark and dichotomous choices, and toward framing them as ideas to be held in balance, encourages dialogue and innovation, adaptation to changing circumstances, more careful prioritization and decision-making, and a focus on the broadest aims of public diplomacy.

Is PD about achieving policy or building mutual understanding?

Historically, practitioners have been divided about the fundamental purpose of public diplomacy. One group views the primary role of public diplomacy as advancing specific, instrumental objectives of U.S. foreign policy. The other group envisions PD as primarily developing mutual understanding and building relationships between the United States and its people, and the people of other countries. The reality is more complex (as most in either camp admit when pushed beyond surface-level arguments). Advancing policy and building relationships are dimensions of public diplomacy that are necessarily intertwined and mutually reinforcing. By promoting U.S. foreign policy and national interests, public diplomacy deepens understanding of the United States and its objectives with foreign audiences and can forge relationships of mutual benefit with key audiences and actors relevant to those policy areas. By creating relationships between the people and government of the United States and foreign publics, public diplomacy creates the conditions in which efforts to advance U.S. policy are more likely to be successful over time. Modern PD practitioners recognize the value of public diplomacy lies in the intersection and contributions of both the environmental and instrumental approaches to PD.

Is PD primarily about talking or listening?

Public diplomacy professionals are in the business of talking (literally and figuratively) to foreign public audiences. They craft content and deliver it in press releases, speeches and talking points, social media campaigns, programming and events, broadcasts, written materials, and one-on-one interactions. Public diplomacy professionals must also be in the business of listening (literally and figuratively) to foreign public audiences to understand them and use that understanding to inform policy decisions. They collect data from relevant information sources. They develop intercultural competencies, acquire language skills, and develop personal relationships with key audiences and actors. They listen to what foreign publics have to say about themselves, their communities, and the United States and its policies. Fundamentally, public diplomacy is about effective communication, which involves sending, receiving, and interpreting messages in diverse social and cultural contexts. Successful communication enables public diplomacy practitioners to shape U.S. foreign policy implementation.

Is PD primarily about informing or influencing?

Public diplomacy professionals inform foreign public audiences by accurately explaining U.S. policy and values. The informing function of public diplomacy also advances U.S. values of freedom and openness, and it builds credibility by providing foreign publics access to accurate information. In some cases, providing this information can circumvent local obstacles, such as disinformation or suppression of information, to inform foreign audiences in hostile information environments. At the same time, public diplomacy practitioners seek to influence foreign public audiences to support U.S. policy positions and interests. That is, public diplomacy seeks to convince foreign public audiences to think and act in ways that are compatible with U.S. foreign policy objectives. Public diplomacy works both to build support directly among foreign publics and to foster local conditions for the advancement of U.S. foreign policy goals by shaping the policy environment in which foreign governments operate. The ability to influence is largely based on trust, mutual respect, and understanding. Public diplomacy creates opportunities to build trust and understanding, which facilitates the possibility of influence to achieve desired policy outcomes.

Finding balance

Rather than endlessly swinging like a pendulum reacting to the inclination of a particular moment, the work of public diplomacy is better thought of as an act of creation, connecting the poles. Its role is to forge a relationship between policy and people; to connect talking and listening in effective communication; to create a loop of information and influence that strengthens the engagement of foreign audiences with USG initiatives; to identify and capitalize on specific moments to achieve policy-relevant outcomes within a broader environmental context; and to bind the creative with the logical. We find success in public diplomacy when we balance these competing roles effectively, adapting to changing goals and audiences.

D. The craft of public diplomacy: metaphors for PD practitioners

Is the practice of public diplomacy an “art” or a “science”? In some conversations, “art” and “science” are proposed as opposite ways of seeing and approaching the world. In colloquial terms, “science” is seen as driven by the scientific process, which centers hypothesis testing, causation, data collection, rigor, and improvement over time. When people use “science” as shorthand for Newtonian physics, science is about laws and rules, precision and predictability. In colloquial terms, “art” is seen as driven by inspiration, creative forces, human connection, and vision, often unbound by logic or quantitative measurement. Measuring “value” in art depends on the preferences of the beholder, rather than the intention or actions of the creator.

Yet, all things are not knowable in scientific terms or with scientific certainty. We would probably agree that Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Ada Lovelace, Jill Tarter, Marie Curie, Mae Jemison, George Washington Carver were creative and inspired in their work. We know, too, that artists, including Yo Yo Ma, Lady Gaga, Misty Copeland, Maya Lin, Kehinde Wiley, and Titus Kaphar worked tirelessly to refine their skills and to understand the formal aspects of their work. Public diplomacy incorporates the best attributes of art and science broadly and holistically understood. It is driven by both creative and logical impulses. It is at once knowable and indescribable. It is, fundamentally, human — which leaves space for all sorts of interesting and unexpected things to happen in pursuit of clear objectives and goals.

Metaphors are powerful tools for critical and creative thinking. Exploring different contexts enables us to see different ways of viewing the role that public diplomacy practitioners play in the formation and implementation of U.S. foreign policy. This section breaks down the art and science dichotomy to explore two paired metaphors for the practice of PD: choreographers and conductors, and gardeners and architects. These metaphors rely on the idea of craft — rather than science or art — to express the varied roles and identities of PD practitioners. To practice craft is to blend the worlds of art and science. Craft requires study, expertise, creativity, vision, skill, and practice.

Choreographers and conductors

Public diplomacy practitioners are choreographers.53 * Choreographers design and coordinate movements, which, when performed together, create specific effects via storytelling and movement. By bringing an audience into the world they create, they shape an audience’s response. Public diplomacy practitioners devise initiatives and activities to advance specific policy objectives and help design and coordinate the presentation of the United States’ public image to foreign public audiences. As leaders within PD sections, public diplomacy officers and Locally Employed staff supervisors may direct and advise on rather than administering the initiatives and activities themselves. They understand how disparate pieces fit together to make a coherent whole. PD sections may choreograph engagements and set a broad vision, then leave the specifics up to implementing partners, grantees, and exchange participants. Once choreographed, the choreographer is no longer performing, instead relying on others to translate their careful planning and vision into experiences.

Public diplomacy practitioners are conductors.54 Conductors lead by bringing experts together, in concert. As musical scores and performance become more complex and require rehearsal and orchestration, the conductor’s role becomes more important. But for many conductors, a sign of success is an ensemble that plays so well together they are not needed at all. The conductor envisions the orchestra and its players as a single organic system, rather than discrete elements that only need to perform their function exactly. Similarly, PAOs lead and coordinate the public face and engagement of an embassy by employing all the sections and specialties at an embassy to meet mission objectives. In this endeavor, they act as the conductor for all those instruments. They conduct not only the quartet or a small group of twelve in the PD section, but also the public engagement of a mission or bureau as a whole. They work to deploy, shape, and coordinate all aspects of public communications to achieve harmony and balance. The practitioner’s conducting work may happen subtly and out of the public eye as in opera. They are bringing people in at the right moment, with the right tools for the task, signaling and coordinating a big picture that few individual instrumentalists focused on playing their own parts well would be able to see.

Gardeners and architects

Public diplomacy practitioners are gardeners.55 Gardeners cultivate a vision, over time, within a complex ecosystem using a specific set of tools and techniques, but for which the final result is dependent on forces largely outside their control. Still, gardeners seek to harness those conditions. They study and make adjustments for soil conditions and weather patterns, anticipate how to deal with pests, and plant seeds knowing it may take months or years to see their vision realized. Gardeners tend to their plants and nurture their development. They weed the garden to remove competition for nutrients; they trim back plants in the fallow season; they water and fertilize each plant to bring out its potential. The returns for public diplomacy are rarely immediate, and public diplomacy practitioners must act in the present to achieve future effects. Thus, they must study the environment and their aims carefully and consider how best to achieve them with the tools they have available. Even with the most careful audience analysis and segmentation, PD practitioners may have to change their inputs and actions based on emerging environmental conditions. They control what they can and respond to circumstances outside of their control based on data and evidence derived both from past experience and the expertise of others. PD practitioners toil in all phases: they are present in the sowing, the caretaking, and the harvest.

Public diplomacy practitioners are architects. Architects take a vision and turn it into a plan that can be realized in a constrained environment. Architects study the terrain and the physical and spatial environment, and take into consideration the function and form that a structure should take. They inform their design with a study of cultural norms and expectations, engineering constraints and the clients' and audiences' concepts of beauty. They design the foundation and layout first, then the framework to provide the structural stability to hold levels, floors and roof. PD practitioners are expert readers of the environment and of building structures to support policy advancement over time. They understand the technical requirements and specifications for media engagement, for writing impactful speeches and press releases, for managing grants, and for planning events. This technical expertise enables them to design buildings that harmonize the information environment, the crafted program design and messages, and human interactions, just as architects seek to harmonize the natural environment, the built environment, and human interactions with it.

Importantly, with each of these metaphors, the idea of craft emerges quite plainly. Choreography, conducting, gardening, and architecture are fundamentally creative, human endeavors that are honed by practice, study, and habit. These endeavors are informed by core principles, data, and logic. In each field, the best individuals are attentive both to the theories and concepts that underpin the work and to their application in the real world.

Rather than rigidly adhering to a set of rules, they know which ones to follow, which ones to bend, and which ones to break. They are focused on achieving outcomes, even if every experiment does not yield the desired or expected results; ballet dancers and gymnasts fall all the time as they learn. Still, they are guided by both rigorous process and inspiration.

Practicing the craft

As a creative, human endeavor informed by theory and achieved in the real world, the contemporary practice of public diplomacy requires innovation: trying new things, finding new audiences, and testing new ways of communicating. The twenty-first century information environment invites public diplomacy professionals to seek out new technologies, platforms, and techniques. At the same time, the craft of public diplomacy demands PD practitioners and experts attend to developments in a wide variety of fields and contexts, and apply them to specific situations

E. Conclusion

Frameworks, mental models, and metaphors are tools for practitioners to forge a shared vision for their profession. The ones offered in this chapter provide starting points for discussion, reflection, and engagement, but they are far from the only ones available.

Thinking figuratively, rather than literally, about the work of PD professionals allows us to see the world more expansively, which can open up new connections and pathways. If we imagine ourselves as choreographers, we may soon find ourselves in the company of (metaphorical) musicians, dancers, set designers, publicists, agents, arts foundations, philanthropists, and patrons. But if we are architects, our network may be made up of city planners, engineers, contractors, suppliers, clients, landscape designers, developers and stone masons. Our networks and associations change how we understand the world and how we approach problems.

Likewise, thinking figuratively and creatively may allow us to take new perspectives, simply by enabling us to ask different questions. If the team is stuck on a problem, try asking different team members to tackle the problem from different points of view. How would a gardener—thinking about cultivating the soil and producing a long-term vision, perhaps unconcerned with the short-term messiness—approach it? Or how would a choreographer—whose role is planning and coordinating the movements of others—approach the same issue? How about an architect—someone with a vision, working within the constraints of political and bureaucratic realities to make it happen in the real world? What other metaphorical lenses might help you see the problem in a new way? Metaphors are powerful tools, but they are often culturally specific. In choosing and discussing metaphors, make sure you are selecting ones that are culturally-resonant with your team and in your context.

By engaging in communication and reflection on these shared models and identities, practitioners can begin to engage in shaping the identity and tradecraft of public diplomacy in the future. This work is an important part of professional development and the identification of public diplomacy as a profession.