Principles of PD: How Public Diplomacy Works

To achieve U.S. policy objectives, advance long-term goals, and promote U.S. national

interests, the modern public diplomacy section must be able to plan and implement PD interventions to affect the attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors of priority foreign audiences. To do this, PD practitioners engage with foreign audiences that hold a range of attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to U.S. foreign policy interests and who live in countries that are friends, allies, partners, competitors, and adversaries to the United States. These high-level alignments then are translated into day-to-day, on-the-ground interactions. PD professionals interact with a variety of foreign audiences in immediate ways, both in deliberate, planned contexts and in responding to events and news around the world in ways that are consistent with U.S. policy, interests, and values. But these immediate interactions take place in information environments that may be shaped for years, and toward policy goals that may be decades in the making.

For the United States, public diplomacy advances U.S. foreign policy goals by shaping information and policy-making environments for international actors, affecting the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of foreign public audiences, and integrating our understanding of public needs and interests into effective policymaking. These ends are accomplished in four primary ways: by understanding, informing, influencing, and building relationships with selected foreign public audiences to achieve carefully chosen PD outcomes through a specific set of means: that is, the set of public diplomacy tools, programs, messages and interventions available to practitioners. Each of these elements of PD strategy is described in depth below.

A. The goals (ends) of public diplomacy

For the United States, public diplomacy seeks to accomplish three primary goals, with the ultimate aim of advancing U.S. interests and foreign policy priorities:

1. affect attitudes or behavior among specific public audiences to support or advance specific U.S. foreign policy priorities;

2. create conditions in policy and information environments that support U.S. interests or deny our adversaries’ interests; and

3. integrate a deep understanding of foreign publics and their interests into more effective U.S. foreign policy.

The most direct public diplomacy engagements seek to persuade selected audiences to take specific actions that support U.S. foreign policy objectives, as defined in strategic guidance documents such as the National Security Strategy or a mission’s Integrated Country Strategy. In less direct forms, public diplomacy seeks to shape a foreign actor’s information and policymaking environment, enabling an actor to take or refrain from taking specific actions. This goal is often accomplished by improving U.S. credibility or legitimacy on a specific issue, or weakening a competitor’s credibility or legitimacy. Finally, public diplomacy is essential for ensuring that foreign publics’ interests and needs (and not just those of governments) are accounted for in the policymaking process. Understanding the specific policy objectives for a given issue is paramount for translating broad policy guidance into specific plans and implementing strategically-oriented public diplomacy work. This understanding and application enables PD to achieve policy goals through designing effective public engagement, influencing information environments, and shaping more effective policy.

B. The concepts (ways) of public diplomacy

As public diplomacy is an inherently rhetorical activity designed to affect foreign audiences’ values, beliefs, desires, and fears, its methods align roughly with those of effective rhetoric. Effective practitioners of public diplomacy analyze and understand their audiences to determine what kinds and combinations of appeals are most likely to be effective.

Information campaigns appeal to audiences logically by providing facts (logos, in traditional rhetoric). Influence campaigns often appeal to audiences' emotions (pathos). And building relationships relies upon establishing the credibility of the United States or its interlocutors (ethos). This section outlines four primary ways that practitioners engage with foreign public audiences in overt, attributable public engagement. Each of these engagements can be carefully selected for different audiences at different moments and may be used in combination with each other. In a particular communication context, for example, a PD section may be trying to inform and to influence, but these are distinct communication goals.

Understanding

Public diplomacy seeks to understand foreign audiences for two primary reasons. First, understanding audiences is critical to designing effective approaches to engagement that advance foreign policy objectives. Second, understanding audiences helps U.S. diplomats advise policymakers on decisions that affect both U.S. and foreign publics. Understanding is achieved through reciprocal communication with key audiences. Public diplomacy adopts a constructionist or constitutive model of communication, which asserts that communication results from interactions between participants to create and share meaning.49 Sophisticated listening requires practitioners to cultivate strategic empathy (that is, understanding another actor’s underlying motivations, interests, and constraints) and to engage in perspective-taking (that is, to see the world from another actor’s point of view).50

Public diplomacy practitioners strive to understand foreign audiences by collecting, analyzing, and applying data and insights from all relevant information sources. Important sources of data and insights include national and regional public opinion surveys, focus groups and interviews, program participant questionnaires, participant observations, informal and formal meetings, program evaluations, and media data collected in-house or by independent experts. Locally employed PD staff can help to provide contextual insights based on their intimate knowledge of the host country. Professional analyses and in-house studies of host country communication patterns (e.g., social media sentiment analysis, content analysis of media reports, advertising trends, etc.) also offer insights into the perceptions of key audiences. Public diplomacy practitioners employ cross-cultural competence, critical analytical skills, and knowledge of the local language and environment to develop a sophisticated understanding of foreign audiences; these abilities also enable them to maintain personal relationships with key audience members and influencers and to tap into local networks.

Informing

PD practitioners engage foreign audiences to explain U.S. policy and U.S. values and, through providing accurate information, build support for them. Public diplomacy seeks to frame and shape media and public discourse to the benefit of the United States and its interests. Public diplomacy practitioners articulate official policy to inform foreign audiences. What distinguishes the inform mechanism from others is a commitment to accuracy, transparency, and objectivity. Historically, the United States has invested significant resources in PD programs and projects that serve to inform foreign publics, especially through broadcast mechanisms such as Voice of America and other global platforms such as its flagship social media handles.

Thus, informing also works to advance professed U.S. values (e.g., truth and freedom of the press) and builds credibility and trust in the United States by providing access to accurate information in a variety of formats. For example, a speaker series may feature experts on a salient policy topic. Programs designed for youth engagement may also use sports or the arts to convey information about civic engagement or preventing violence. Social and traditional media facilitate sharing information about the visa application process and explaining a U.S. position. Providing information access can also advance free and open information environments, which is crucial to providing counter-narratives and informing audiences in hostile information environments.

Influencing

In addition to informing foreign public audiences, many public diplomacy initiatives and activities are designed to persuade and influence their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Public diplomacy aims to build support among foreign publics for U.S. policy goals and objectives directly, and fosters local conditions conducive to the advancement of U.S. policy goals by encouraging foreign publics to pressure their government to take positions that align with U.S. foreign policy goals, interests, and values. The U.S. Government also works to influence foreign publics through indirect engagement, by cultivating key influencers for specific audiences. The U.S. Government may not always be the best messenger for important communication, in which case advocates and influencers have the potential to amplify the United States’ reach and effectiveness. Building support through communication is most effective in an atmosphere of trust and in the context of genuine relationships. Developing trust in U.S. leadership among foreign publics increases the effectiveness of persuasion and influence.

Building Relationships

Relationships with foreign public audiences are at the core of public diplomacy’s capacity to understand, inform, and influence. Public diplomacy aims to build multiple types of relationships between individuals (e.g., academic and professional exchanges); groups of individuals or networks (e.g. informal networks based on interest or experience; formal networks, such as societies or associations); and organizations (e.g., universities, cities and municipalities, nongovernmental organizations, cultural institutions). Public diplomacy practitioners also develop relationships with journalists and other press and media organizations; cultivating these relationships is essential for successful public diplomacy work.

Public diplomacy also plays a role in building and maintaining government-to-government relationships with select branches of foreign governments (e.g., ministries of information, education, or culture) that shape, and sometimes control, the way their citizens perceive the United States. For example, many public diplomacy programs are coordinated with one of these ministries, such as binational commissions for the Fulbright Program, and a public diplomacy professional may be a direct liaison with an official from the ministry of education. If educational and cultural programs are administered and supported by the national government, the United States may find itself with direct interests in how the education system shapes students’ views of the world and of the United States. Similarly, a public diplomacy officer may work with a ministry of foreign affairs official to coordinate messaging on a bilateral agreement or a meeting between high-level officials. Thus, public diplomacy practitioners may act as formal or informal contacts with government officials with particular portfolios related to education, culture, and information.

C. Translating PD concepts (ways) into PD outcomes (ends)

In the course of understanding, informing, influencing, and building relationships, public

diplomacy initiatives and activities pursue a common set of PD outcomes. These outcomes describe the effects of a program or intervention. They are pathways toward achieving the primary ends, that is, advancing U.S. foreign policy, described above. These are the specific contributions that PD makes to achieving broader foreign policy objectives or advancing broader foreign policy priorities. They include:

● Raising Awareness: Increasing a foreign public’s knowledge of specific facts or information.

● Affecting Attitudes: Reinforcing, changing, or diminishing an idea, perception, belief, or feeling held by a foreign public.

● Affecting Behaviors: Prompting a foreign public to take (or stop taking) a specified action, or to increase (or decrease) the frequency of a specified action.

● Relationship Building: Establishing or strengthening relationships between people or groups of people. These relationships may be between U.S. Government staff and a foreign public, between people in the United States and another country, or between foreign publics.

● Organizational Partnership: Establishing or strengthening a relationship between institutions or groups of institutions. These partnerships are situated institutionally rather than personally, and may be between a government and various civil society organizations, cities or provinces, non-profit organizations, universities and academic institutions, professional organizations, cultural institutions and museums, private organizations, and many others.

● Skill Building: Seeking to improve a foreign public audience’s proficiency with specific skills relevant to U.S. policy objectives, such as civic and economic participation, good governance, rule of law, or respect for human rights.

D. The PD toolkit: The means of public diplomacy

The tools available to today’s PD practitioner vary by the type and duration of the intended impact and the breadth of the intended audience. PD practitioners must identify specific outcomes that need to be achieved to advance a policy goal, understand the potential influential and affected audiences on the topic, and select appropriate priority audience(s) for engagement. These factors guide the practitioner’s selection of tools for and approaches to delivering content, facilitating public engagement, and, ultimately, advancing

U.S. foreign policy.

Public diplomacy tools work through different causal mechanisms (i.e., the process or pathway by which an outcome is brought into being). PD practitioners leverage their knowledge of U.S. policy and local context to apply these different mechanisms effectively across a range of issues at different levels. Some tools and programs are designed to achieve concrete short-term objectives, such as crafting press guidance for a VIP visit.

Others serve more enduring and overarching policy objectives, such as cultivating

long-term partners and advocates to align foreign publics’ values, attitudes, and interests with the U.S.

Just as U.S. policy objectives evolve, PD platforms, programs, and tools change as well. These tactics are not tied to specific objectives or limited by geography, allowing the PD practitioner to apply best practices to local opportunities and challenges within different contexts. Most PD tactics (e.g., activities, programs, messaging across media platforms) can be structured and combined to address a range of audience groups and policy objectives. For example, English language education and programs may achieve a variety of objectives: they offer participants skills necessary to access information about the United States, they open the door to the possibility of study in the United States, and they also provide opportunities for PD practitioners to listen to and understand key audience segments of the host country. The specifics of English education or English-language programing, however, will vary from post to post and can change over time as the Department tries new approaches, changes focus areas, needs to reach new audiences, or desires to achieve different policy objectives. In modern PD, the focus should be on advancing the desired policy goal with a carefully-selected audience, rather than on simply running a program well.

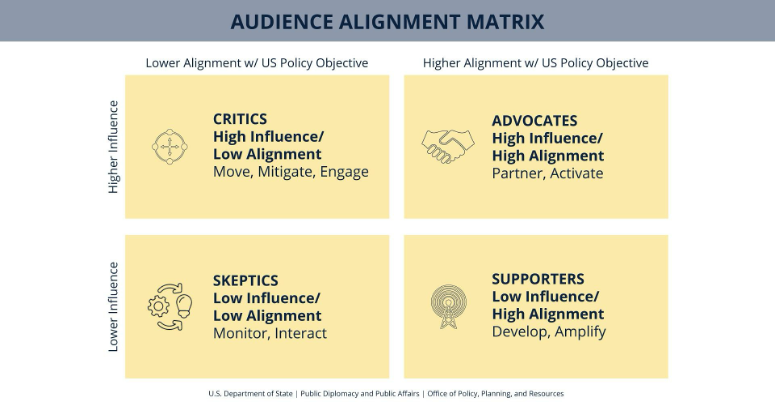

Thinking critically about audience alignment and engagement

Identifying audiences within the broader public that are moveable on specific U.S. interests allows PAOs to focus the deployment of limited financial and personnel resources with the right audiences at the right time using the right tools to achieve the greatest impact.

Ultimately, we want to move individuals and audiences: to convince a critic to no longer publicly oppose our position, to encourage a silent supporter to defend our interests, to empower our allies and partners to advocate on our behalf, and so on.

A simple 2x2 matrix that accounts for audience alignment and audience influence can help practitioners deploy the PD toolkit to maximize engagement with different types of audiences. Using this matrix is explored in more detail in PD Foundations, “PD in Practice, Appendix A” as a fundamental part of audience research and analysis.

High Influence/Low Alignment (Critics)

Groups in this quadrant often pose a challenge for PD practitioners because the section would be trying to move or shift their opinions on an issue, or to mitigate the influence of opinions that are not closely aligned with the U.S. policy objective. This work may be extraordinarily time or resource intensive. They have influence but are likely using that influence to send messages that oppose or in some other way do not support U.S. objectives. Still, the PD section probably doesn’t want to ignore this quadrant altogether; instead, the section can think about how to mitigate influence or how to engage in ways that may make incremental moves.

High Influence/High Alignment (Advocates)

Groups in this quadrant are well-positioned to become partners, if they aren’t already. Their interests and priorities overlap with those of the United States and the mission and because their voices carry weight with priority audiences the PD section wishes to reach. This quadrant is where the section may find groups or individuals who fall in the “Established Opinion Leaders” cluster on a particular topic or issue. The PD section seeks to help activate or partner with this group, so the investment of the section’s time and resources may be significant here.

Low Influence/High Alignment (Supporters)

In this quadrant, focus efforts to develop or amplify a group’s influence. Because they align with U.S. interests and objectives, they are great connections, but their voices may be drowned out or unheard, so they may have relatively little effect on influencing a priority audience’s attitudes, beliefs, or behavior. This quadrant is where the section may find groups or individuals who fall in the “Emerging Voices” cluster on a particular topic or issue. Therefore, the PD section’s focus may be to develop their networks, amplify their voices, and increase their level of influence with other audiences and groups while maintaining their alignment.

Low Influence/Low Alignment (Skeptics)

Groups in this quadrant may be frustrating to engage because it can be difficult to see a return on investment; if a group has few overlapping or aligned interests, but is not influential or presenting a barrier to influencing priority audiences, there may be little direct gain from engagement. But thinking about ways to monitor and interact with them in light-touch approaches may be a better choice. That is, the PD Section can keep an eye on their position and potential movement and interact with them on their terms.

A tool such as the audience alignment matrix will not make a section’s decisions about which audiences to engage. In some cases, engaging the critics may be the best investment of a section’s time and resources, whereas in other cases, the section will gain more traction and movement toward the policy goal by amplifying the voices of their supporters who are highly aligned but not very influential. Again, PD sections will have to make choices and prioritize to achieve strategic effects. Fortunately, they have many tools to assist in the process.

Once a PD section has identified a priority audience, the PD section then has to decide how best to engage the audience to achieve the desired outcome. The next section outlines six ways that PD sections engage with foreign public audiences. Because specific tools and practitioner habits may shift over time, this section is organized by communication mechanism, rather than activity type, and outlines logic, examples, and details of each mechanism.

Listening

Systematic listening to foreign publics, collecting data and evidence and analyzing that information to contextualize and advance the U.S. foreign policy agenda, is a critical skill for all public diplomacy practitioners. Systematic listening ensures the PD section is listening to a strategically relevant and wide array of influential voices on a given issue or policy area. Active listening requires engagement from the listener to accurately paraphrase and reflect what has been said. Empathetic listening requires that PD practitioners engage in perspective-taking and withhold judgment while seeking to understand the perspective of the relevant audience. Skill in communicating in languages other than English enhances PD practitioners’ abilities to listen effectively.

How does this work?

Mechanism: Audience → USG

Causal logic: Systematic, active, and empathetic listening to foreign publics enables PD practitioners to understand the local contexts in which U.S. foreign policy is formulated and conducted and to understand the specific preferences and needs of foreign public audiences.

Desired outcomes: Relationship building Time horizon: Short, medium, and long term

Tools for systematic, active, and empathetic listening include:

● Systematic engagement with contacts outside of the embassy or consulate, including people whose views may not align with the USG

● Monitoring local press coverage and opinion pieces on items of U.S. and local interest

● Monitoring local social media accounts and tracking analytics

● Reading and analyzing public opinion polling

● Analyzing social media content and engagement

● Conducting focus groups with program participants or members of prospective and intended audiences

● Conducting surveys of program participants

● Conducting in-depth interviews or semi-structured interviews with key participants

● Conducting participant observation

● Conducting nationally representative surveys

● Reading and analyzing relevant analysis from third-party organizations, such as academia and think tanks

● Observing and understanding non-verbal communication signals

● Identifying local narratives on foreign policy issues

● Understanding formal and informal means of communication within local networks

Unmediated Engagement

Some PD engagement with foreign publics is direct: USG officials and employees engage directly with priority audiences and selected audience segments, and do so without an intermediary or interlocutor. For example, if the Ambassador hosts a dinner at their residence for NGO leaders on human rights issues and delivers remarks, they are engaging directly with a foreign audience. If the U.S. Embassy hosts an in-person event and streams part of it, it is engaging directly with the invited audience and with those who are watching it online.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG → Audience

Causal logic: Specific messages are directed at relevant audiences to directly inform and influence their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Desired outcomes: Raising Awareness, Affecting Attitudes, Relationship Building Time horizon: Generally short term

Unmediated engagement tools include:

● Public appearances, including speeches and other public events are relatively unmediated opportunities for USG officials to speak to or interact with foreign public audiences.

● Official websites are designed and maintained by the USG to provide accurate and relevant information directly to an online audience.

● Programmatic emails, calls, debriefs, etc. allow USG employees to connect directly with people who have shown interest in USG programming, attended a PD event, or are already part of the mission’s contacts. Contact Relationship Managers (CRM) enable direct communication with alumni, youth network members, event attendees, and other contacts.

● Meeting with state or government organizations on issues of mutual interest and involvement to achieve PD objectives, for example, meeting with the Ministry of Education to articulate shared goals of improving English language access in schools.

● Meeting with individual contacts and organizations on issues of mutual interest is often a key first step in cultivating relationships that yield demonstrable outcomes.

Press and platform-mediated engagement

Public diplomacy teams often rely on traditional, digital, and social media platforms to distribute messages attributable to the U.S. Government. These platforms are mediated, as algorithms and editorial choices put one step of distance between the U.S. Government and its selected audience.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG → Press and Media platforms → Audience

Causal logic: Specific messages are directed at specific audiences to inform them and to influence their attitudes and behaviors.

Desired outcomes: Raising Awareness, Affecting Attitudes, Affecting Behaviors Time horizon: Generally short term

Examples of press and platform-mediated engagement include:

● Social media posts enable the U.S. government to communicate and engage directly with priority public audiences. In addition to short-term messaging, social media platforms provide a means of tracking submitted responses to USG messages and serve as virtual spaces for convening and maintaining relationships with communities interested in medium- to long-term interaction with the United States.

● Paid media and advertising, including print, broadcast, advertising and social media are a means of communicating with a wider audience.

● Press releases and recordings of important events or speeches, particularly when released in their entirety, inhibit misinterpretation, provide audiences with access to original source material relevant to policy topics.

● Traditional press communications, including press releases, events, interviews, statements and other activities to communicate U.S. government messages through the media. Press communication generally plays a public affairs role in conveying accurate information about U.S. policy. When directed to foreign audiences, engagement in the local press plays the additional role of communicating information to advance U.S. policy, that is, to persuade, generate support, and influence behavior and attitudes.

Broadcasting

Public Diplomacy also engages foreign public audiences by disseminating objective, unbiased news and information through traditional broadcasting methods. Direct international news broadcasting has been an important part of the U.S. public diplomacy toolkit since the Second World War. Today, primary responsibility for international broadcasting belongs to the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), described in more detail below. Importantly, there is an editorial firewall between USAGM and other USG organizations, which means that the U.S. Government is not involved in the content or editorial decisions made by USAGM journalists or editors.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG Supported International Broadcast Media → Foreign Public Audiences Causal logic: Presenting an objective, journalistic, news-oriented view of world events provides foreign publics with access to information about the United States, its policies, and its people, which influences foreign publics’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the United States.

Desired Outcomes: Raising Awareness, Affecting Attitudes Time horizon: Short term

Activities that support broadcasting include:

● The United States Agency for Global Media seeks to inform, engage, and connect people around the world in support of freedom and democracy by providing multimedia broadcast distribution in a range of strategically important languages, as well as technical and administrative support to the broadcasting networks. USAGM manages a global network of transmitting sites and an extensive system of leased satellite and fiber optic circuits, along with a rapidly growing Internet delivery system servicing all USAGM broadcasters. USAGM Broadcast networks include the following:

○ Voice of America

○ Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

○ Office of Cuba Broadcasting (Radio/TV Marti)

○ Radio Free Asia

○ Middle East Broadcasting Networks (Alhurra TV and Radio Sawa)

○ Engagement through intermediaries and interlocutors

While some public diplomacy interventions move directly from a USG messenger to a foreign public audience, other engagements are conducted through intermediaries: USG officials and employees engage with individuals, organizations, and partners, who then communicate with foreign public audiences. Here, the PD goal is to persuade influential supporters to advocate on our behalf. Interlocutors and intermediaries are usually influencers or advocates who are, for a variety of reasons, more credible or influential messengers with an intended audience than a USG official or representative. The engagement takes place with the goal that an interlocutor will engage a foreign public audience in ways that advance U.S. foreign policy objectives.

Press and media partners

Press and media contacts cultivate their own audiences that often overlap with priority audiences for advancing U.S. foreign policy. Engaging with press and media contacts and organizations as intermediaries for foreign public audiences also creates opportunities for PD practitioners to communicate through them with their respective audiences. Approaching press and media as audiences in and of themselves can also advance U.S. policy priorities related to press freedom, countering disinformation, and good governance. Persuading influential, trusted media personalities to advocate for our policy positions increases the public's openness to our position.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG → commercial and independent press and media professionals →

Foreign public audience

Causal logic: Media outlets offer important venues and opportunities for USG officials to shape and distribute key messages related to U.S. policy positions and priorities. Local media coverage is designed to reach a broad local audience, including groups and contacts to which the U.S. Government may not have direct access.

Desired outcomes: Raising Awareness, Affecting Attitudes, Affecting Behaviors, Building Relationships

Time horizon: Short-term for specific stories and events; long-term to shape the media landscape

Press and media engagement tools may include:

● Press tours sponsored by a post may allow foreign journalists to tour an American embassy or to travel to the United States to engage with U.S. media outlets and reporting opportunities.

● Arranging partner media engagements enables the United States and its implementing partners to strengthen media networks and capacity within a host country.

● Access to information for international journalists about the United States and American foreign policy via The Foreign Press Center (GPA), through direct advising, assistance with scheduling and accreditation to official press offices, and by organizing thematically focused tours for groups of foreign journalists.

● Briefings for international journalists are primarily offered through the Office of International Media Engagement (GPA), which include the State Department's six Regional Media Hubs. These Media Hubs engage overseas audiences through foreign-language broadcast, print, and web interviews and operate the Department’s foreign-language social media feeds.

Skill building

Skill-building can be a feature of public diplomacy programs (both public diplomacy information programs and exchange programs) and foreign assistance programs. In assessing which type of programming (and funding) is suitable for a given skill-building activity, the answer will depend on the intended objective or goal being supported.

Skill-building may be incorporated into a public diplomacy information program where the objective is to improve those skills that would enable participants to take actions that advance U.S. policy, interests, and values in key areas, including supporting the rule of law, freedom of expression and other human rights, expanding economic prosperity, and civil society.

Skill-building may be incorporated into exchange programming where the objective is to further mutual understanding and people-to-people contact. Skill-building is often a component of foreign assistance programs as a means of furthering foreign assistance objectives, including building the capacity of foreign partners in areas of mutual interest. This project is focused on public diplomacy tools and addresses skill-building in that context only.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG → Implementing partner (NGO or other institution) → Audience Causal logic: Providing workshops and training to build skills within a particular foreign audience and enable that audience to support or amplify U.S. government efforts to distribute information about the United States, its people, and policies or to build mutual understanding and support people-to-people connections

Desired outcomes: Skill building, Relationship building, Affecting behaviors Time horizon: Medium to long term

Skill-building programs and activities may include:

● Journalism workshops improve the capabilities of foreign journalists to research, investigate, and report information based on the best practices of a free and independent press. Journalism programs and media literacy education establish important relationships between the U.S. government, U.S. and international journalists, and foreign key media influencers. These activities aim to foster open and resilient information environments where democracies can thrive and which further disseminate accurate information about U.S. policy and shared values.

● TechCamp creates hands-on, participant-driven workshops that connect private-sector technology experts with key populations (e.g., journalists,non-governmental organizations, civil society advocates, students) to explore and apply innovative tech solutions to global issues. TechCamp workshops are focused on tangible outcomes, with participants identifying real-world challenges and working in partnership with trainers during the workshop to apply technology solutions to these challenges.

● Youth Networks (including YALI/YLAI/YSEAL/et. al) are a strategic tool to allow PD Sections to reach a wider audience beyond the US mission’s typical sphere of influence and cultivate a community of individuals interested in connecting with the U.S. government on policy issues. Networks build the leadership capacity of emerging leaders and promote community action in support of U.S. foreign policy objectives. Through a campaign-style approach to public diplomacy engagement, Network members are encouraged to use Department-provided resources to organize projects, community dialogues and awareness campaigns on policy topics that resonate locally. This structure enables U.S.-driven content to reach audiences beyond a PD section’s normal capacity, including people critical for policy objectives but who only speak a local language, cannot read, or are located in remote villages or security no-go zones for U.S. personnel, without expending additional Post resources.

● Entrepreneurship workshops empower entrepreneurs with business skills that align with U.S. values and a free and fair global market. These workshops aim to increase economic prosperity - often among disadvantaged and underserved communities - by providing participants with the entrepreneurial skills to improve economic participation for themselves, their families, and their communities.

● English language programs provide teachers of English with materials and training for effective language teaching and imparting accurate information about the United States. English language training offers skills required for direct access to accurate information about the United States, expands opportunities for future leaders to study in the United States, and develops a relationship between a mission and policy-relevant communities. When English is the common language among foreign audiences in a country or a region, the U.S. Government can more effectively communicate its policy, which can build relationships with individuals and institutions, and improve relationships between our governments.

● The U.S. Speakers program recruits and deploys subject-matter experts from academia, civil society, and the U.S. private sector to participate in speaking engagements, workshops, and policy-focused programs organized by U.S. embassies and consulates overseas. Bringing in U.S. subject matter experts aids in building policy expertise and networks around the world.

Enabling people-to-people connections

Colloquially known as exchanges, these programs facilitate people-to-people communication and relationship-building between U.S. and foreign individuals. Exchanges can build skills and knowledge, enhance network development, and encourage participants to share their experiences with others. Exchanges bring individuals from foreign countries to the United States, and send U.S. citizens to foreign countries, to participate in educational, professional, artistic, athletic, and cultural activities. These people-to-people connections may also emphasize short-term policy education and persuasion initiatives.

For the U.S. government, exchanges are generally focused on building understanding and respect between counterparts in the United States and other countries. Through their exchange experience, U.S. participants form personal relationships with their foreign host communities, increasing understanding of the principles behind USG policy. In the other direction, foreign exchange participants form relationships with their U.S. host communities and the U.S. government. These relationships form the basis for future direct engagement with that individual and, ideally, their network, while providing valuable context and guidance to mission decision-makers.

How does this work?

Mechanism: U.S. citizens ← USG funding and support → Foreign citizens

Causal logic: Build relationships that enable effective communications and build mutual trust and understanding to enable future advancement of U.S. interests.

Desired outcomes: Affecting attitudes, Relationship building, skill building Time horizon: Medium and long term

Activities that support people-to-people connections include:

● Academic exchanges, including the Fulbright Program, Global UGRAD, and the Community College Initiative Program, among others. Some of these programs only bring foreign students and teachers to the United States, while others also send U.S. students and teachers abroad.

● Professional exchanges, including the Fulbright Humphrey Program, the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) the Congress-Bundestag Vocational Youth Exchange Program, and others, seek to develop long-term relationships with future leaders of government, business, and civil society.

● Sports and cultural exchanges, in which U.S. and foreign individuals or groups gain understanding and build support for U.S. values by engaging on a shared topic of interest to facilitate relationships and the development of positive attitudes toward the United States.

● BridgeUSA, the collective term for private sector exchange programs, spans 13 categories, including: Alien Physician, Au Pair, Camp Counselor, College and University Student, Intern, Professor, Research Scholar, Secondary School Student, Short-Term Scholar, Specialist, Summer Work Travel (SWT), Teacher, and Trainee. These programs provide opportunities for visitors from over 200 countries and territories to experience U.S. culture and engage with Americans, increasing mutual understanding and developing "citizen ambassadors" who return home eager to stay connected and explore future exchange opportunities. Promoting study abroad and international education for foreign students to study in the United States and for U.S. students to study in other countries. Through the EducationUSA program, the U.S. government provides unbiased admissions counseling and assistance to foreign students applying to universities in the U.S.

● Alumni engagement activities sustain the U.S. government’s relationships with alumni of exchanges and leverage their influence to support U.S. policy objectives.

Building institutional relationships

While people-to-people exchanges cultivate relationships between individuals, organizational partnerships formalize relationships between institutions. These institutions may include academic, cultural, economic, and political organizations. By facilitating partnerships between U.S. institutions and their foreign counterparts, a mission can engage priority audiences connected to those foreign institutions. Institutional relationships facilitate people-to-people relationships, and vice versa. Often, public diplomacy supports the creation of formal institutional partnerships between U.S. and foreign counterpart organizations to advance shared strategic goals. Formal partnerships are typically funded through the award of a grant to a U.S. institution (or consortium) stipulating the specific types of activities or exchanges that are to be carried out under the grant or cooperative agreement.

How does this work?

Mechanism: USG → (Intermediary U.S. organization ← → Intermediary host country institution) → Audience

Causal logic: Build organizational relationships that facilitate mission access to networks of interest, model civil society and community relations best practices, and support sectoral people-to-people exchange of information, expertise and institutional leadership skills.

Desired outcomes: Relationship building, Affecting attitudes Time horizon: Medium to long term

Activities that support building institutional relationships include:

● Federal Assistance Awards, such as grants and cooperative agreements, provide USG funding to recipient organizations to support a broad range of programs and

activities. In addition to supporting exchanges, training, speaking engagements, media activity, American Spaces partnerships, or other types of programs, the awards establish relationships with recipient organizations and contribute to the development of civil society.

● Public-Private Partnerships between the U.S. government and private-sector organizations, NGOs, or consortia (for example, the American Alliance of Museums) to undertake public programs that advance U.S. interests. The U.S. government typically formalizes these partnerships in memoranda of understanding.

● Diverse contact networks enable the U.S. government to identify synergies and opportunities for the achievement of shared objectives by connecting local organizational partners that would not otherwise encounter one another.

● World’s Fairs and International Exhibitions offer opportunities for the United States to participate in and potentially host major international exhibitions that aim to educate the global public, promote progress on issues of mutual concern, and foster cooperation among the international community.

● Universities and educational institutions are common sites of organizational partnership in the public diplomacy world. They facilitate academic exchanges; host and provide experts, researchers, and speakers; serve as institutional hosts for American Spaces; and provide space for the free exchange of ideas.

Information Access

Information Access engagement facilitates access to relevant and accurate information about the United States and its policies to inform audiences abroad about U.S. policies and priorities. By providing access to accurate information and/or information directly from the

U.S. government, public diplomacy informs priority audiences and builds credibility with them. When deployed in countries that lack an open media environment, information access engagements increase the amount and improve the quality of information, news media, social media, people-to-people communications, etc., foreign audiences receive and consume. By providing access to information in addition to providing information itself, U.S. public diplomacy advances the U.S. value of freedom of information and builds trust with audiences.

Mechanism: Marketplace of ideas ← USG support → Audience

Causal logic: Increased access to accurate information will lead to increased support for

U.S. values and policy.

Desired outcomes: Affecting attitudes, Affecting Behaviors, Skill building, Raising Awareness Time horizon: Short, medium and long term

Activities that promote information access include:

● Media literacy campaigns and other initiatives supported by the Global Engagement Center to counter the spread of mis- and disinformation.

● English education programs and resources to enable foreign audiences to better connect with U.S. media, culture, and policy. The Regional English Language Office provides online and printed English teaching materials and guidance. Fulbright scholarships and the English Language Fellows program also send English teachers from the U.S. to teach English overseas.

● Visual media provides a powerful means of connecting foreign audiences to implicit and explicit information relevant to U.S. policy. Film screenings, photography exhibits, and art installations influence attitudes and beliefs about U.S. policies through the culture and values they depict.

● Technology tools to identify, analyze, and counter disinformation and propaganda campaigns.

● Physical and electronic access to books and periodicals through American Center libraries.

● Internet censorship circumvention technologies like those supported through the USAGM Open Technology Fund enable citizens of foreign countries to bypass internet censorship imposed by their governments.

E. Tying it all together

Strategy is active, rather than being a static document or plan. It is best understood as the ongoing alignment of ends, ways, and means, formulated and accomplished in a complex environment and under constraints. Public diplomacy practitioners support U.S. policymakers by providing them with information about foreign publics' perspectives and actions, which should in turn shape U.S. strategy and policy. As strategic thinkers and planners in their own right, PD practitioners work to achieve particular foreign policy objectives by affecting change in the attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors of foreign public audiences and by shaping the global information environment (ends). Public diplomacy enables the United States’ advancing these goals by understanding, informing, influencing, and building relationships with relevant foreign public audiences (ways) by employing a specific set of public diplomacy interventions from the PD toolkit (means). Taken together, these ideas build the core logic of public diplomacy: engaging foreign publics to promote understanding of and support for the United States and its policies.