PD In Practice: Section I - Introduction and the Public Diplomacy Framework

A. Policy-centered, audience-focused, data-informed public diplomacy

Public diplomacy advances U.S. strategic objectives and foreign policy goals by engaging with specific audiences through thoughtful planning and implementation of specific PD initiatives, activities, events, programs, and network building. This work should be informed by data, research, and evidence at every step in the process. Policy-centered, audience-focused, data-informed public diplomacy relies on key messages carefully designed and delivered to reach a particular audience to influence their attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors.

This document is intended for any PD practitioner who wishes to understand an ideal process for the development and execution of PD programming and messages, from a Public Affairs Officer (PAO) to senior Locally Employed staff (LE staff), to civil servants in Washington, to foreign service officers working in a regional PD office, to a deputy chief of mission (DCM), to PD-coned entry-level officers, to LE staff just joining an embassy team in a PD section, and others. In this section, the mission’s PD section at an overseas post is the central unit of action, with the PAO as the key figure in leading, guiding, and supporting the PD section and the mission through the process. Readers can orient themselves this way in relation to the PAO and the PD section at an overseas post. They may also translate from this context to their own, for example, by understanding references to the Integrated Country Strategy (ICS) to be roughly analogous to a Functional Bureau Strategy (FBS) for a domestic PD office, or the Joint Regional Strategy (JRS) for a regional PD office. In conjunction with other training opportunities, this section of PD Foundations walks through the ideal process for PD practitioners to design, plan, implement, manage, and assess PD work in the field.

Whereas prescriptive policy guidance, law, and regulation shape both policy and practice, this document sets out standards that will contribute to the advancement of U.S. foreign policy by instilling habits of mind and ways of working that are connected to best practices in design, analysis, planning, implementation, management, measurement, and evaluation. PD Foundations, even though it operates as guidance for the practice and discipline of public diplomacy at the State Department, does not seek to present a process that is a rigid, lockstep, all-or-nothing proposition. Rather, it seeks to articulate what a rigorous approach to strategically-oriented PD efforts would look like in practice. The approach can and will change as the PD landscape changes and will be shaped both by grassroots, bottom-up input and by top-down direction.

For consistency and simplicity, the process outlined in this section uses the ICS sub-objective as the starting point for conceptual and detailed planning. However, PD practitioners should keep in mind that the ICS is nested within a strategic ecosystem, where the intent is to advance U.S. interests along a broad set of aspirational objectives and goals. Creating PD initiatives that advance U.S. foreign policy priorities and produce concrete policy outcomes is critical for PD work, and PAOs should work intentionally with the country team in the ICS drafting process to ensure it provides sensible strategic direction for the PD section. Ideally, these objectives will be articulated in the ICS and will flow logically from mission goals, to objectives, to sub-objectives that direct the work of the mission.

Still, there may be cases where ICS sub-objectives are not helpful starting points for developing policy-oriented PD initiatives and activities. For example, it could be the case that a mission objective presents better opportunities for targeted PD work, or that changing local, regional, or global circumstances mandate a shift in strategic direction. Such variations are to be expected. These limitations in the structure of formal strategic documents, and even in some cases in the tools that are currently available to PD practitioners, should not impede the intent of the PD Foundations project: to lay out sound design, planning, management, and evaluation principles to guide policy-oriented PD work.

PD sections may have to respond to emerging regional or local crises or developments that may not be captured in the ICS. PD initiatives should strive, always, to advance post, bureau, or other U.S. government (USG) policy priorities, regardless of whether they are captured by the ICS. Finally, PD practitioners in the field must remain responsive to the requirements and requests of their chiefs of mission and front offices. Nonetheless, working to ensure that public diplomacy remains tightly linked to the ICS helps PD practitioners balance these competing demands.

All these considerations should be captured in the annual Public Diplomacy Implementation Plan (PDIP) process, where PD teams articulate their strategic planning vision, but also update their plans as global and regional priorities emerge or as the local situation changes. The PDIP is the place where strategic planning meets detailed planning; it lays out the PD section’s plan to make real the objectives outlined in strategic documents. The initiative is the key pathway to link strategic concepts to tactical actions. The tools and processes outlined here are flexible and adaptable; PD practitioners can and should modify them to suit their context, planning timelines, scale, and purpose. Likewise, R/PPR acknowledges the need to continually update technology, tools, and training to meet practitioner needs.

B. Constraints, challenges, and straight talk

PD practitioners face many challenges throughout their careers. Examples follow.

- There is not enough time.

- There is not enough money.

- There are not enough PD personnel.

- The demands from my front office are incompatible with strategic planning.

- The demands of Washington are incompatible with strategic planning.

- The ICS is not the only source of strategic or policy direction.

- The ICS doesn’t accurately reflect my mission’s goals right now–it’s out of date or narrowly written.

- There are many existing and long-standing programs with great support and popularity that don’t always seem to fit into a strategic-planning paradigm.

- It’s hard to say no.

- It’s hard to measure the effectiveness of PD initiatives and activities.

- The lines between public diplomacy, traditional diplomacy, and direct assistance seem to be blurring.

- The lines between public diplomacy and development can be hard to define.

- U.S. policy is in a state of flux and always changing.

- We do not have the right set of knowledge, skills, capabilities, or capacity in the PD section to accomplish this kind of work.

These constraints and challenges are real. There is never enough time (or people, or resources). PD sections are pulled in many directions by many powerful stakeholders. Sometimes formal and informal processes haven’t kept pace with changes in the strategic environment and in the information environment. Measuring the effectiveness of PD programs can be extraordinarily difficult.

PD Foundations will not eliminate the challenges of doing public diplomacy in the contemporary environment, but it can help shape how PD practitioners respond to them. This publication guides practitioners toward five habits of mind and ways of thinking and working to align with the broader goals of accomplishing policy-centered, audience-focused, data-informed public diplomacy for the Department and for the advancement of U.S. interests. PD Foundations supports practitioners in taking the following actions:

- To think strategically about aligning resources to achieve U.S. foreign policy goals and objectives.

- To plan and implement effective PD initiatives and activities designed for specific relevant audiences to advance specific U.S. foreign policy priorities.

- To assess PD initiatives to improve them and to enable a culture of organizational learning.

- To articulate to internal and external stakeholders the value of public diplomacy in achieving U.S. foreign policy goals.

- To develop modern, collaborative, and data-driven PD teams that work across the PD section and throughout the mission in pursuit of policy goals and objectives in ways that build the capacity, abilities, and morale of our personnel.

Changing our ways of thinking and working is a challenging task that requires concerted effort and leadership. PD Foundations helps the PD community, collectively, to take the next right steps.

C. The Public Diplomacy Framework

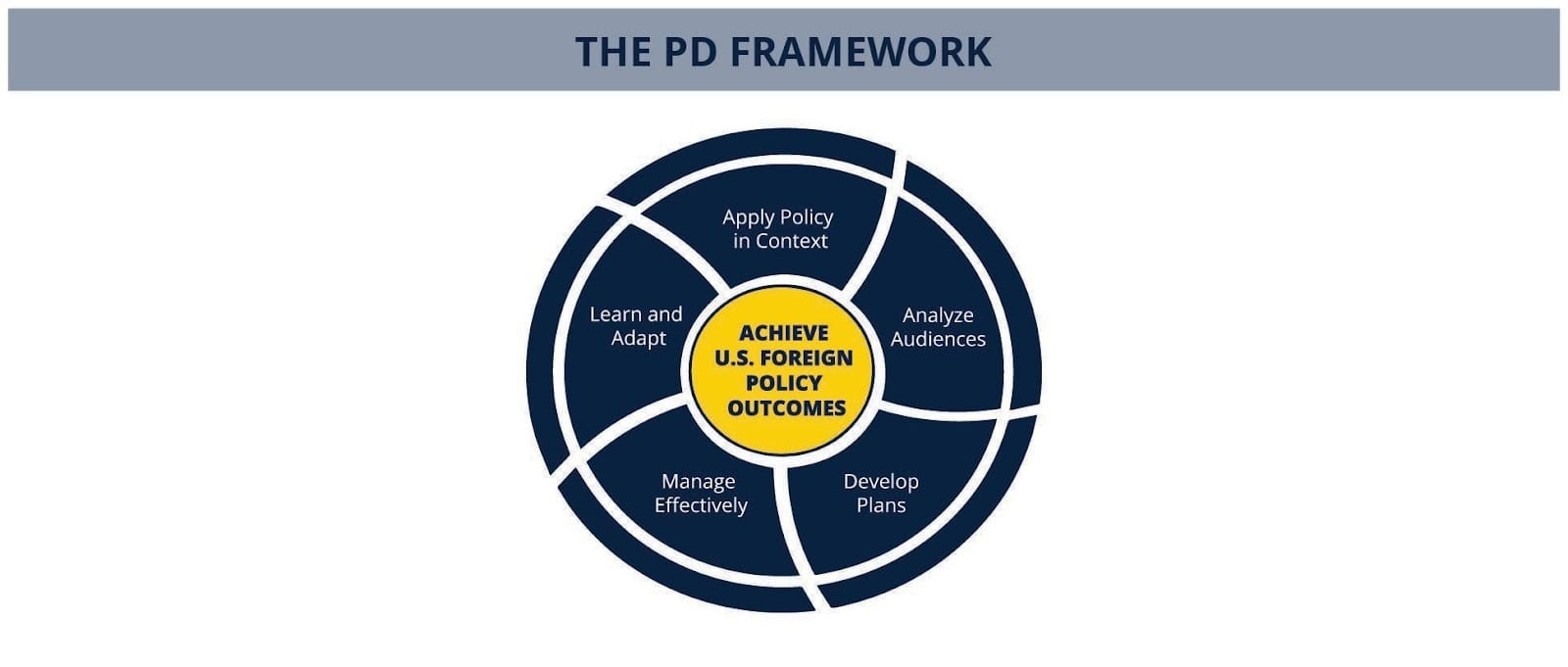

The Public Diplomacy Framework (PD Framework) articulates five elements to describe and guide the conduct of modern, professional public diplomacy work. Modern PD is adaptive, policy-centered, audience-focused, data-informed, and designed to deliver demonstrable foreign policy outcomes. The PD Framework also guides the effective use of the Department’s PD resources in advancing U.S. foreign policy priorities.

A graphic representation of the PD Framework, depicted in Figure 1, shows five equal elements in relation to each other and to the ultimate purpose of public diplomacy, which is to achieve U.S. foreign policy outcomes.

Figure 1. The Public Diplomacy Framework

- Apply Policy in Context: Develop a comprehensive understanding of U.S. foreign policy goals and objectives in the relevant local context to determine the role public diplomacy plays in advancing specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

- Analyze Audiences: Identify specific audiences from among the key stakeholders on an issue and select audience segments whose attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs are most likely to bring about the desired policy outcomes for PD initiatives and activities.

- Develop Plans: Create actionable plans tied to clear policy aims and measurable objectives to employ appropriate public diplomacy tactics with defined audiences to advance specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

- Manage Effectively: Set a common strategic vision to enable meaningful contributions from the full PD section and other partners and allocate resources to efficiently and effectively implement and monitor public diplomacy initiatives and activities.

- Learn and Adapt: Monitor and assess whether public diplomacy initiatives and activities are meeting their objectives: report on outcomes, analyze and share results, collect and refine best practices and lessons learned, and use data to adjust plans and inform future efforts.

More detailed information on the PD Framework can be found in the volume Principles of PD, Chapter 4: The profession and craft of public diplomacy.

Apply Policy in Context

Develop a comprehensive understanding of U.S. foreign policy objectives in the relevant local context to determine how public diplomacy efforts can contribute to the advancement of specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

The United States seeks to advance its interests and values in the world by using the instruments of national power – diplomatic, information, military, and economic. U.S. foreign policy goals are laid out in a nested series of guiding documents that include the National Security Strategy (NSS), the Joint Strategic Plan (JSP), and JRS, and conclude at the bilateral level with the ICS, and in functional bureaus with the FBS. PD practitioners take policy direction from these guiding documents, as well as administration officials who decide and set additional strategic direction and indicate policy priorities. In order to effectively translate high-level policy guidance to planning and implementation of specific interventions, programs, and messages for public audiences, PD practitioners must be well versed in U.S. foreign policy goals and the ideas that underpin them. Additionally, PD officers must be familiar with the local contexts in which they work. Effective practice includes knowing key historical, cultural, political, and social factors (among others), including prevailing narratives about the United States’ role in the country, region, and world, and how they present obstacles or opportunities for the United States to achieve its aims. Based on a thorough knowledge of U.S. policy objectives, national and regional contexts, PD practitioners can best determine and employ PD techniques and practices to understand, inform, and influence foreign publics strategically toward advancing defined policy objectives.

Analyze Audiences

Identify specific audiences from among the key stakeholders on an issue and select audience segments whose attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs are most likely to bring about the desired policy outcomes for PD initiatives and activities.

Audiences are a central concept within public diplomacy. Effective public diplomacy outreach, messages, and programs have a clear concept of which audiences matter for which policy results and how best to reach those audiences to understand, inform, influence, or build networks to advance a desired policy objective. Analyzing audiences is the process of using evidence to identify and define a priority audience. The goal of this process is to identify a clear and narrow priority audience around which to design activities and engagement whose attitude or behavior change is necessary to achieving our desired foreign policy outcomes. With those priority audience segments identified, PD practitioners must think about how best to engage that audience using public diplomacy tools and resources.

Develop Plans

Create actionable plans underpinned by sound causal logic and measurable objectives to employ appropriate public diplomacy tools with defined audiences to advance specific U.S. foreign policy goals.

Public diplomacy planning should be integrated within broader mission, interagency and national security planning processes. Plans should be grounded in an articulated theory of causation (e.g., X action causes Y response), and the logic that underpins this should also be transparent (e.g., X action causes Y response because of Z mechanism). Prioritizing sound causal logic prompts PD practitioners to examine and articulate why they are developing plans in a certain way. The PDIP is an ongoing operational process that documents the connections between the public diplomacy section’s work and the larger aim of advancing mission priorities articulated in the ICS or bureau strategies. PD practitioners are encouraged to use a design approach to understand policy guidance, frame the environment, write problem statements, and develop PD initiatives and activities that employ the full range of public diplomacy tools to advance U.S. foreign policy objectives. For a more detailed discussion of the design approach in public diplomacy, refer to Public Diplomacy in Practice, "A design approach to public diplomacy".

With key initiatives identified, practitioners then engage at the detailed planning level. PD professionals build initiatives and activities that deploy a variety of outreach capabilities to generate immediate results and longer-term effects. For a more detailed discussion of detail planning, refer to Public Diplomacy in Practice, "Section IV. Detailed planning". They design engaging, relevant content and experiences to reach priority audiences. To measure the effectiveness of public diplomacy initiatives and activities, PD professionals establish SMART objectives and articulate a hypothesis that proposes a causal relationship between the PD initiative or activity and a desired attitude/belief/behavior change.

Manage Effectively

Set a common strategic vision to enable meaningful contributions from the full PD section and allocate resources to efficiently and effectively implement and monitor public diplomacy initiatives and activities.

Effectively managing PD outreach, engagement efforts, and the workings of a PD section supports the mission’s, department’s, and nation’s long-term success. As conscientious stewards of U.S. taxpayer funds, PD practitioners ensure that their resources align to foreign policy priorities and that their use of funds follows U.S. law, policy, and guidance. PD practitioners must be effective coordinators for press, events, and public engagements. PD officers and Locally Employed staff supervisors should create supportive and inclusive work environments where every member of a PD section can contribute meaningfully. PD practitioners manage relationships and contacts every day. PD leaders invest in developing capabilities and capacity in their sections. Effective management is largely about prioritizing and applying resources to achieve maximum impact. These resources include the time and talent of team members as well as financial and material resources.

Learn and Adapt

Assess whether public diplomacy initiatives and activities are meeting their objectives, report on outcomes, analyze and share results, and use data to adjust plans and inform future efforts.

Learning and adapting requires a clear understanding of the objectives of public diplomacy initiatives and activities, reliable assessment of whether they achieved their objectives, honest appraisal of why they succeeded or failed, and the lessons that can be gleaned and applied in either case. Learning and adapting (a) starts with understanding policy objectives, defining audiences, and designing initiatives and activities that influence those audiences toward a desired policy objective, (b) continues through monitoring and/or evaluation against objectives, and (c) concludes with reporting and sharing results and applying new insights to improve future planning.

Monitoring, evaluating, reporting, and learning are essential components of government-wide best practices for grant and project management. They respond to requirements by Congress, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the Government Accountability Office (GAO). These core capabilities for learning and adapting apply to PD tactics and resources as well. Monitoring is regular data collection intended to document what happened with a certain initiative, activity, or event. Evaluation is the collection and analysis of data to determine how well, if at all, an event, activity, or initiative met its objectives. Reporting creates usable records at post (so a team’s successors can assess what has been done before in order to make sound decisions and plans) and in Washington (which reduces the need for redundant global data calls).

Learning and adapting from insights based on monitoring, evaluation, and reporting enables PD practitioners to continuously improve, scale, and replicate successful initiatives and activities and is essential to continuous improvement. Programmatic improvements demonstrated in one country or context can often be applied to improve effectiveness in other geographic, cultural, and demographic contexts. Accumulating and distributing such evidence creates a body of knowledge that PD practitioners and program designers can draw on when advancing new priorities or confronting new challenges. Department policy on program and project design, monitoring, and evaluation under the Managing for Results (MfR) Framework can be found in 18 FAM 301.4.