PD In Practice: Section II - Strategic Planning and Audience Analysis

A. Introduction

“How do we get from where we are to where we want to be, without being struck by disaster along the way?” -Paul H. Nitze

As one public diplomacy scholar asserts, “Strategists are people who seek to solve problems and make choices related to a desired future.” PD professionals are strategic thinkers and planners. Their work must connect to broader strategic goals. This connection explains the choices PD practitioners make about tactics, resources, and activities to achieve policy outcomes.

To think and act strategically, PD professionals must set priorities and ensure that their resources, practices, and goals align with mission objectives. Strategic planning enables PD practitioners to maximize their impact on U.S. foreign policy by using their expertise to engage foreign audiences effectively. This allows them to shape policy, collaborate across the mission, and adjust to changing circumstances.

A clear strategy brings teams together around a shared vision and guides them toward partnerships that help achieve U.S. foreign policy goals. Strong strategies also enable PD professionals to design programs and initiatives that can be evaluated for impact, adjusted as needed, and meaningfully contribute to the broader goals of the mission, the State Department, and the nation.

B. Exercising judgment

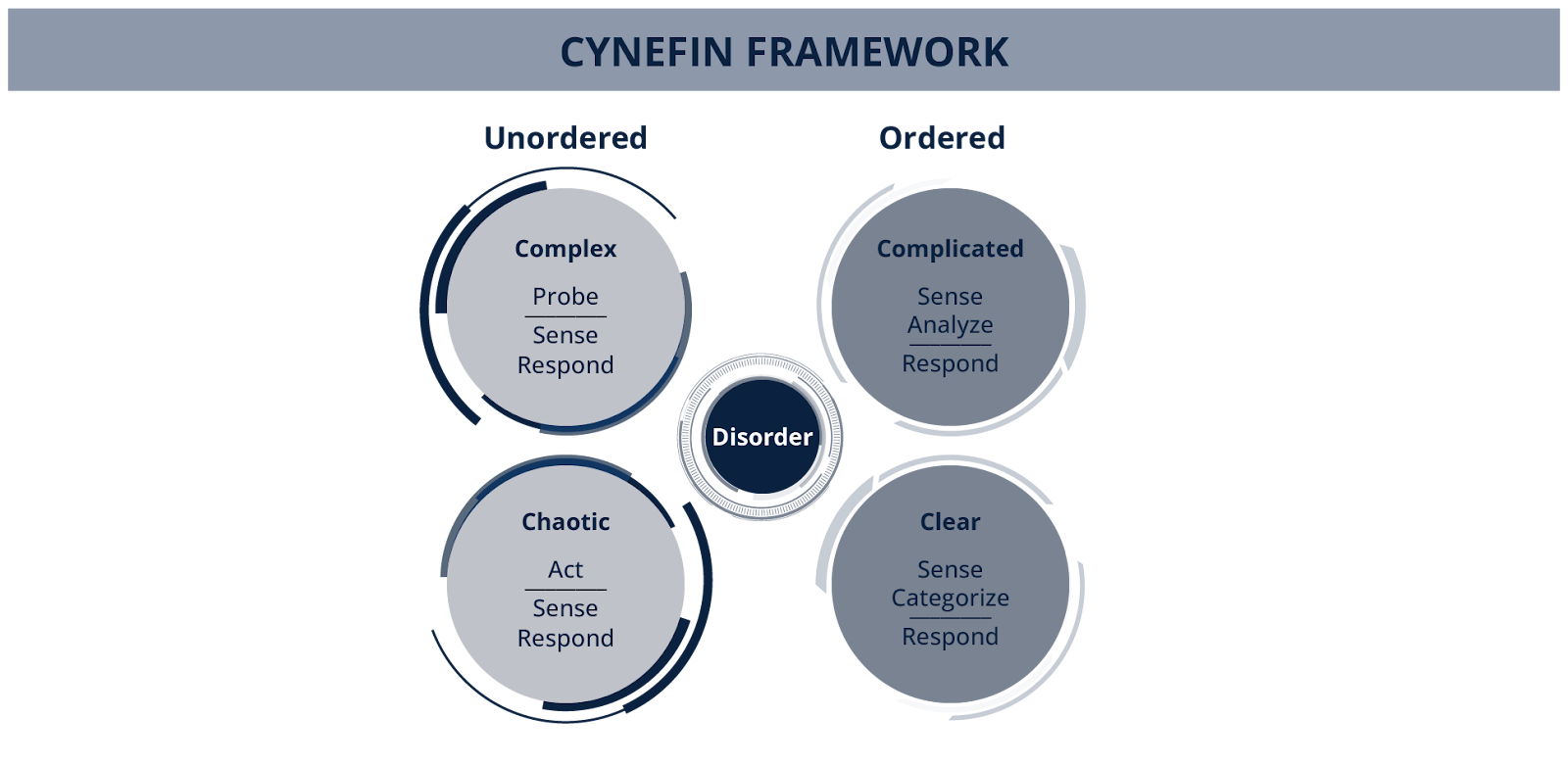

Thinking strategically results in taking purposeful action in response to strategic and policy guidance, understanding the environment, thinking critically and creatively about how to achieve goals, advocating for and allocating resources appropriately, and adapting in the face of uncertainty and change.

Strategists and planners operate in a world with incomplete information. PAOs may be working with an ICS that does not currently reflect the mission’s priorities or that does not fully articulate the U.S. foreign policy objective at stake. There may be conflicting priorities between Washington and the mission’s front office, or conflicting guidance from Washington. In light of these challenges, strategic planning requires that we ask difficult questions; think clearly about costs, risks, and benefits; analyze trade-offs; and make difficult decisions. In short, strategic thinking is about the exercise of expert, professional judgment in complex contexts.

What is strategic planning?

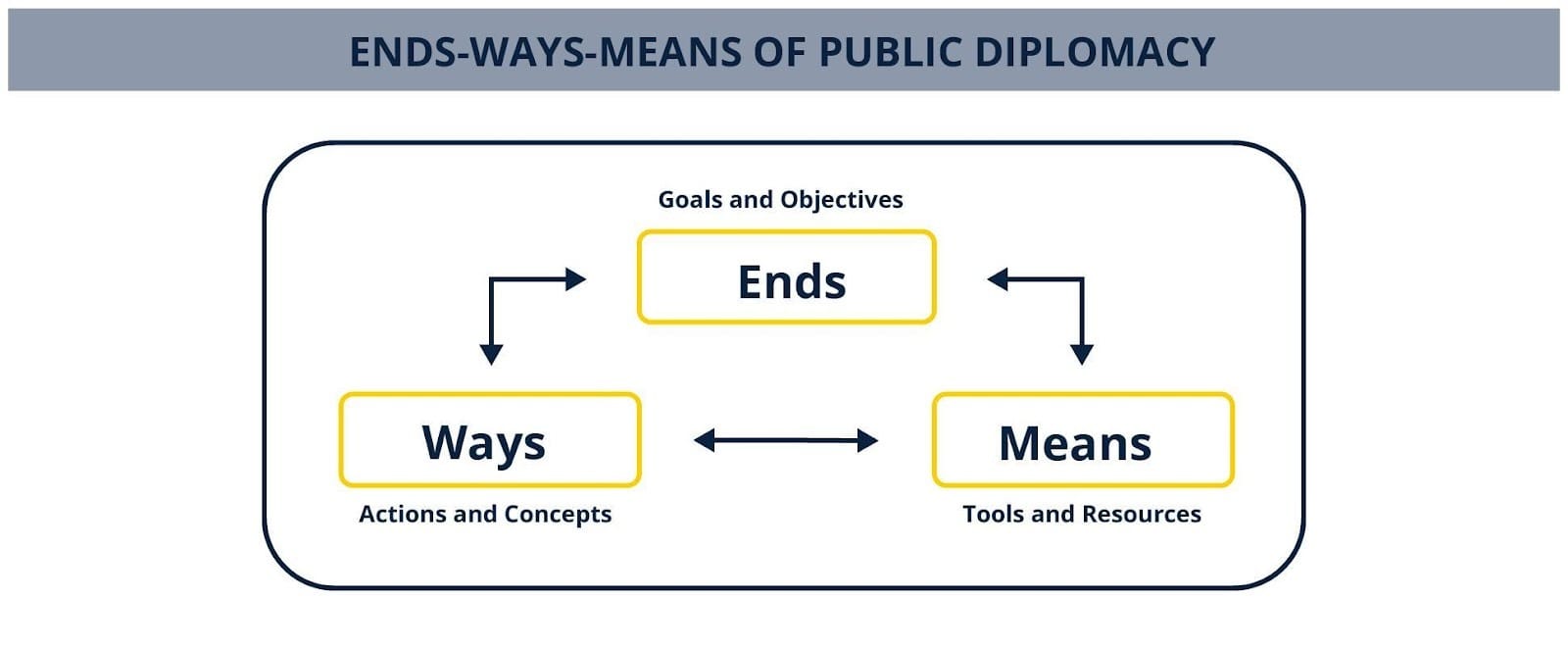

Strategy is about explaining how resources (what you have), actions (what you plan to do), and goals (what you want to achieve) are connected. “Principles of Public Diplomacy” explains how policy, strategy, and tactics work together. When someone can show clearly how their planned action will lead to the desired outcome or make a meaningful change, then the plan has solid reasoning and has sufficient detail. When initiatives and activities lack sufficient planning and strategic framing, it is difficult to ensure that U.S. resources–provided by the U.S. taxpayer–are being responsibly managed. The results of weak causal logic range from activities and initiatives being irrelevant to a strategic problem (the best case) to their actively working against a strategic objective (the worst case).

Choosing the best strategy begins with understanding the relationships you see between means, ways, and ends. While we are moving toward more data-and evidence-driven decisions, our logic is often informed by our experiences and analogies, and it’s often implicit. For example, U.S. foreign service officers may take an experience from their last post and use it to frame or understand a challenge at their current post. LE staff may have a finely honed sense of how to reach a particular audience segment based on their knowledge of local culture and trends. Experience provides important evidence for decision making, but it must be paired with data and evidence from other sources. Thinking strategically and working to effect change in the real world requires the application of judgment on the part of planners.

Figure 2. Ends-Ways-Means

As you move to link strategy and tactics, you need tools and processes to help you make causal links clear and meaningful, and to coordinate and prioritize various tactical engagements to create strategic coherence. At overseas posts, the ICS represents the most detailed formal strategic guidance from which PD practitioners pull to implement their work. Joint Regional Strategies (JRS) also represent strategic guidance for PD professionals. For Functional Bureaus, the equivalent source is the FBS. Posts may also receive strategic guidance from their chiefs of mission and take direction from other key leaders in the Department and administration.

Strategic documents in particular provide PD professionals in the field with a broad, whole-of-mission strategic framework that is focused on identifying and enumerating goals and objectives. Using them to inform strategic planning can help PD practitioners focus their efforts around widely cleared, vetted, and available language, which can help them create internal coherence and buy-in as they develop long-term plans. This chapter focuses on using the ICS as a starting point for strategic planning, focusing on the the first three elements of the PD Framework: Apply Policy in Context, Analyze Audiences, and Develop Plans.

C. What is design thinking? An overview

Industrial designers, architects, and planners first popularized design thinking or design approaches as a way to solve complex challenges. Design thinking has since taken root in many industries and sectors. In the private sector, a design approach focuses on empathy and understanding of the people who are affected by an issue or who will use a product or service. It emphasizes clear problem definition, quick prototyping, testing, and iteration. Design thinking is one way to tackle problem-solving, especially around problems that are ill-defined, loosely structured, complex, and dynamic. A design approach is widely used in the public relations field, for example in designing public health campaigns or other initiatives designed to influence attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Military organizations also have adapted and developed a type of design-oriented thinking, often referred to as operational design, in much of their doctrine to fill the gap between strategy and planning. Design approaches are useful for PD practitioners because they face complex problems in unique environments, develop coordinated efforts in response to these challenges, and have a focus on human relationships and interactions.

Design thinking provides practitioners with a creative and deliberative way to arrive at potential (if partial) solutions to a problem. For PD practitioners, it emphasizes understanding the perspectives and needs of the audiences, actors, and stakeholders involved in an effort to make progress toward an identified ICS sub-objective or other priority. The processes outlined below are, in many cases, adapted from military operational design; that language (wherever possible) has been retained and will enable interagency coordination and cooperation.

Public diplomacy professionals can borrow from design thinking approaches to facilitate creative and critical problem-solving, promote people-centered planning and programming, and ensure their work is relevant to supporting and advancing U.S. foreign policy and national security objectives. Within the PD world, design thinking and approaches should be substantially focused on audiences. However, a PD “audience” is different from a private sector “customer.” PD practitioners identify, analyze, segment, and engage with foreign public audiences to provide a service, advancing U.S. foreign policy to the American people.

But using this approach does not have to be limited to the PD section. Public diplomacy should be part of a whole-of-mission approach to advancing and achieving U.S. policy objectives. In fact, the most effective planning efforts will involve stakeholders from many sections and offices within the post. The approach outlined below can also be a model for integrated planning. How will the PD section work with the Pol-Econ section? What role will USAID play? How will the Defense Attaché Office or U.S. military be involved? What other agencies have a presence, and how does their work contribute to achieving the objective? Working in this way enables integration and synchronization at the highest levels, making the mission’s work more focused and efficient. This section provides a brief overview of the design approach for public diplomacy. The “Design Approach” is explored in more depth, with examples and steps for using it in the context of a PD section.

A series of simple questions can guide a design-driven approach to problem-solving:

- What are we trying to accomplish?

- What is going on right now?

- What do we want things to look like when we’re done?

- What is the problem we need to solve?

- How do we get from here to there?

Written in a different way, as steps in a process, it might look something like the structure below. Each part of the process includes specific analysis of the policy objective, the environment and context, and the audiences for potential PD engagement.

- Identify, understand, and clarify the U.S. policy goal, guidance, and direction.

- Understand and visualize the current environment.

- Identify potential audience groups who are affected by and influential on an issue or topic.

- Map out or visualize the environment, systems, structures, processes, and networks in which influential and affected groups operate.

- Understand and visualize the desired end state and future environment.

- Conduct preliminary research to describe the priority audience groups whose changed attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors are most important to achieving the desired end state.

- Map out or visualize the desired future environment, systems, structures, processes, and networks in which these priority audience groups operate.

- Write a problem statement.

- Develop an approach.

- Select the most relevant and realistically reachable priority audience group(s) that you want to reach through your initiative.

- Brainstorm potential initiatives to reach your selected audiences and advance your policy objectives.

- Evaluate and identify initiatives that will address the identified problem and priority audience groups.

The first three steps might collectively be understood as a situation analysis. A policy-centered, audience-focused design approach for public diplomacy emphasizes understanding, especially understanding of the policy guidance, of the current environment, of the desired future environment, and of stakeholders and potential audiences as part of the environment, even before defining the problem, and certainly before jumping in to figure out what actions you want to take. Given that it can take some time to conduct an initial situation analysis, the process can sometimes seem like it prioritizes theorizing over doing, which can be uncomfortable for practitioners; but deep understanding, based in research and evidence, pays dividends. The results of the situation analysis help to understand and craft the problem statement, and then, the approach and solutions. As the environment changes, as you gain information from executing initiatives and activities, or even as policy goals shift, you can revisit this series of questions. These questions allow you to think flexibly about an issue. When conditions change, you will be well prepared to reframe and iterate.

This process operates at a fairly high level, moving from advancing an ICS sub-objective to identifying initiatives (and potentially some activities, as part of developing the approach). But the questions introduced here are useful throughout the planning process. You can also apply deliberative questioning at many stages in the process of planning, implementation, and adaptation. One key question is, “How do we know?” By asking yourself this question as you consider your operating environment, strategic objectives, initiatives, and activities, you will be well on your way to making decisions that are informed by research, evidence, and data. Developing a culture of asking questions and then seeking evidence to answer them is a critical step in developing cultures that embrace learning and are well-situated for strategic planning and flexible adaptation when the situation requires them.

Desk research

Several steps during the design and planning process involve “desk research,” including situation analysis and audience analysis. Unlike “original research” where a researcher conducts a unique study that generates new knowledge, desk research is the process of searching for existing and available data and evidence on a specific topic, issue, or audience. Desk research is about finding, analyzing, synthesizing, and applying knowledge gained from other people, rather than conducting original research yourself. If you are searching in a database or library catalog, or even just doing a basic search on the internet, you are conducting desk research. Desk research is helpful in understanding the policy objective, defining a PD problem to be solved, mapping the current environment, learning more about an audience, or verifying an underlying assumption or hunch. One important consideration in conducting this type of research is the reliability, credibility, and validity of the sources you are finding. For example, a report from a well-known think tank will provide a different kind of information than that provided by a blog post written by a local university student. Both of these might be useful sources, but you would analyze them differently.

D. Developing a design mindset

Design thinking offers a deliberative, purposeful, and inclusive approach to problem-solving that can be broken down into discrete steps. More importantly, it offers leaders and team members a design mindset: a philosophy or conceptual way of thinking about a problem and possible solutions. A design approach relies on the creativity, perspectives, and collaboration within the team, and it is enhanced when the team brings a range of backgrounds, experiences, and expertise.

A design approach works if everyone involved, from the top down, values and embraces:

- Collaboration and dialogue

- Listening as much as speaking

- A commitment to building strong, well-rounded teams

- Competing ideas and perspectives

- A sense of humility and willingness to learn from mistakes

- The importance of research and data

- Intense curiosity about the way the world works

- The concept of a “learning organization”

- A deep understanding of resource assets and constraints

- A shared understanding with those who will implement the plan

A design approach cannot work if any of the following holds true:

- There is a lack of enthusiastic support from leadership

- Only one “voice” dominates

- Expertise is not respected

- There is no commitment to iteration and adaptation

- There is no tolerance for failure or ambiguity

- The conceptual vision is not clearly communicated

The PAO's support plays the most important role in developing a design mindset within the team. The PD section can also work to cultivate a design mindset within the broader mission, as they are primed and trained to ask questions about goals and priorities, understanding the environment, defining problems, and developing solutions. When a design mindset is also supported by bureaus and offices in Washington, the possibilities for effective strategic planning; evidence-based decision making; and more effective policy-centered, audience-focused PD initiatives are amplified. This amplification occurs when all parts of the PD community share a vision for planning and executing strategically relevant programs designed to achieve specific effects in the real world.

E. The design approach is audience-centered

Effective public diplomacy outreach, messages, and programs have clear target audiences, allowing them to reach those audiences and advance a desired policy objective. Analyzing the most effective target audience involves using data and research to narrow your focus from the entire universe of groups and individuals who may be relevant to a U.S. foreign policy objective, to defining the specific group whose attitudes or behaviors will need to change in order to achieve that objective. Once you have clearly defined your priority audience, you will be able to use that information to develop a message and choose a messenger that is most likely to reach and persuade your priority audience.

Having limited resources means that no initiative can reach all audiences. Audience analysis helps identify the most appropriate audiences, messages, and channels for PD initiatives. It provides a road map for reaching those who are most likely to engage in your desired behaviors identified in the problem statement.

PD initiatives cannot reach everyone, and not every person in a country is going to be influential in helping the mission accomplish its objectives. The best way to allocate scarce resources is to identify priority audiences.

Just as there are barriers to change, there are also people who can influence others to change. Identifying the key influencers who can persuade your priority audience to change will allow you to reach those groups, even when they may not be open to changes suggested by the United States. Refer to the mapping findings in the desk research and situation analysis steps and identify the people and processes that may influence the priority audiences’ behaviors.

By considering the influences who are valued by the priority audience, you gain insights into who might be the most influential in moving your priority audience forward. Importantly, the PD initiative may not require direct contact with a priority audience, it may be more effective to reach this audience through an interlocutor or an implementing partner, or through other networks and contacts. While this group of “influencers” may become your target for PD initiatives, it is important to have considered and remain aware of your priority audience. Remember, your priority audience is the group whose attitudes or behaviors need to change to achieve your policy goal.

Key audience definitions

Audience: A group of people who generally exhibit a common set of attitudes, behaviors, or traits, organized around a topic or issue.

Audience analysis: The evidence-based process to identify, select, and define groups whose attitudes or behaviors need to change to achieve a policy objective, and to determine effective ways to communicate with and engage them.

Audience research: The process of conducting research to identify an audience and learn their beliefs, preferences, behaviors, etc. Audience research can be conducted in many ways (e.g. surveys, focus groups) and should be based on rigorous, established research methodologies appropriate for the goal of the research.

Potential audience: A group of people who are affected by a particular policy or issue. These are the people whose attitudes, knowledge, or behavior you are ultimately looking to change.

Priority audience: An audience that you select for targeted engagement with PD programs, initiatives, messages, or other activities. To identify a priority audience whom you can effectively engage, consider the shared knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors that need to change to achieve the policy goal.

Audience segmentation: The process of identifying distinct characteristics within the priority audience, based on shared characteristics like demographics, psychographics, geography, communication preferences, behaviors, or attitudes.

F. A design approach to public diplomacy strategic planning

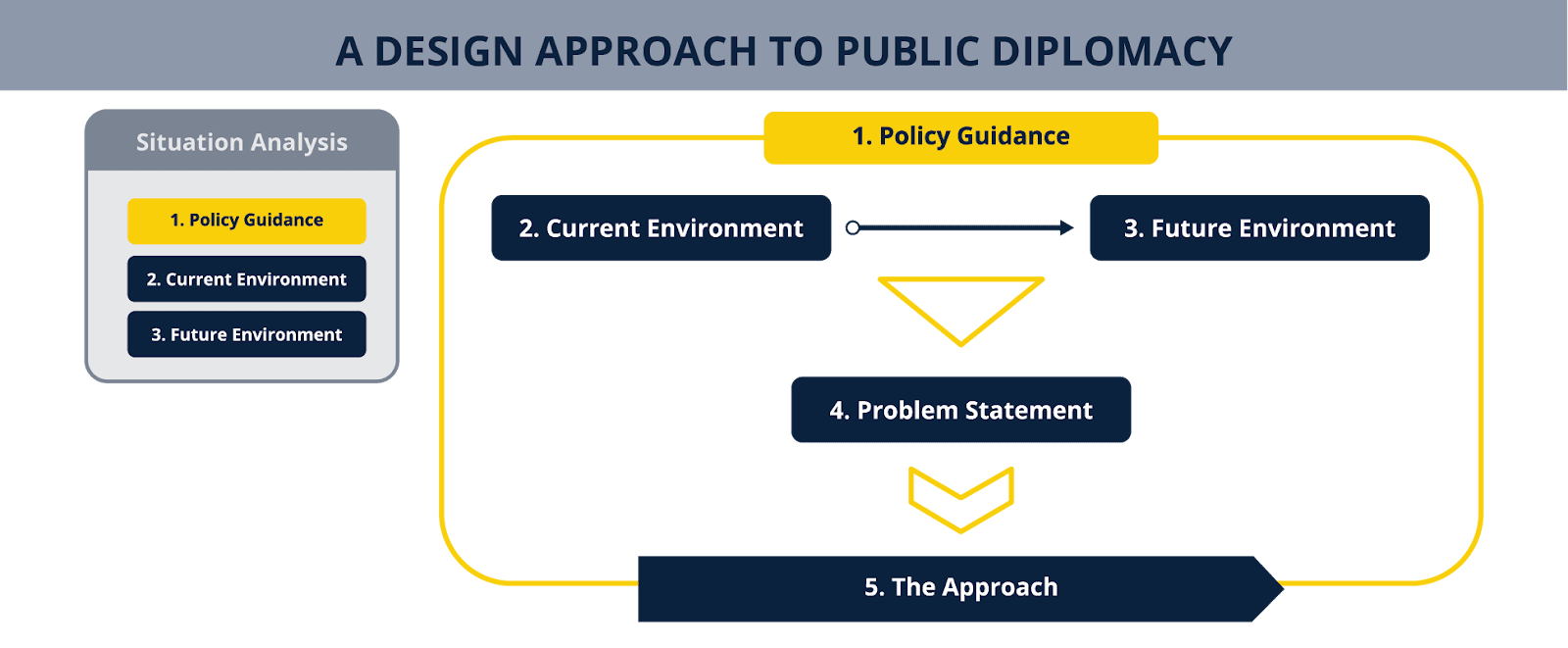

Figure 3. A design approach to public diplomacy

A design approach overview:

- Situation analysis (steps 1-3): In the design approach to public diplomacy, steps one through three (policy guidance, current environment, future environment) are often considered the situation analysis.

- Problem statement (step 4): The result of the situation analysis helps practitioners craft the problem statement to outline the main problem(s) to be addressed and why.

- The approach (step 5): The approach lays out solutions, including brainstorming initiatives and activities to address the defined problem.

1. Step one: Policy – What are we trying to accomplish in terms of foreign policy?

This step centers on thoroughly understanding the existing policy and any related formal and informal direction from leadership at post or in Washington. It requires you to analyze the sub-objectives of your ICS or FBS. This step has three components: (Note: This isn’t where you need to decide what you are trying to accomplish with your PD initiative yet. Instead, ask what is the outcome that the United States as a whole would like to see in terms of U.S. foreign policy?)

- Prioritizing policy objectives for the PD section’s energy, time, and resources. Which policy priorities are most important for your post and why? Out of all the things you could do, why should you be doing this one?

- Researching, understanding, and interpreting the specific U.S. foreign policy goal related to a broad issue or theme (e.g., anti-corruption, climate change, economic prosperity, global health, security) in your local context.

- Articulating the potential PD contribution to achieving the broad policy objective.

Some questions you might ask in this initial step are listed below.

- What is the broad U.S. foreign policy goal or interest that we seek to advance?

- What is the specific policy outcome we are trying to achieve or advance?

- Have some conditions related to the goal or objective already been met?

- Is this a high priority for mission leaders, or for Washington?

- What are the relevant laws or regulations in place that guide work in this area?

- Does the articulation of the goal or objective require clarification or modification?

- Have we received any formal or informal guidance about this objective?

- How relevant is PD work to making progress on this objective?

- What are the relevant authorities for PD work in this area?

- What is the state of the team’s resources (human and financial) and workload?

- What other mission/bureau teams are stakeholders for this goal or objective?

(a) Determining priorities

The design approach graphic, figure 3, provides a model for helping your team (be it in a mission-wide effort, within a functional bureau, or within a PD section) to think rigorously and carefully about how to link PD to strategic objectives. PD work should contribute to a range of ICS goals, rather than be concentrated within a single “PD goal” without trying to do everything everywhere in the ICS, striving beyond its capabilities and resources. That is, PD resources should address mission-wide priorities. But because there are many goals and objectives that an embassy is working toward, spreading PD resources uniformly or thinly across a large number of objectives is also problematic.

Initiatives generated by leadership that are not captured in the ICS or PDIP may also be problematic if they are not clearly aligned with PD authorizations and strategic priorities. At the very least, such initiatives require frank conversations about trade-offs. Thus, PD sections, in consultation with other sections and their front offices, will need to prioritize areas for PD work. Not every mission objective or sub-objective may be particularly conducive or responsive to PD initiatives. You will never have all the time, resources, or human capacity to do all the things you might like to do. You must make choices and then find effective ways to defend and implement those choices.

You can make informed choices by systematically and carefully analyzing your ICS in relation to your PD section’s ambitions and resources and in relation to the overall goals and resources of the mission. You can ask:

- Is the mission still working toward this sub-objective?

- Does PD have a meaningful contribution to make toward achieving this sub-objective?

- Is this sub-objective a high priority for mission leadership?

- Is anyone else in the mission working to address this sub-objective?

It makes sense to explicitly prioritize which goals, objectives, and sub-objectives the PD section is best positioned to support. Based on these strategic priorities, planners should consider what, if any, contribution PD can make toward accomplishing specific sub-objectives. Finally, even at this early stage, the PD section should begin to think about how resources (especially money and staff time) align with priorities. Priorities can be very abstract until resources are attached; for example, if you have limited resources to devote to a stated priority, this disconnect might prompt you to reconsider whether the stated priority is really a priority or whether more resources need to be funneled to it. Here, your understanding of policy guidance and strategic priorities, your technical expertise as a PD professional, and your local expertise about the context in which you are operating all come into play. See Appendix A: Prioritization tools.

(b) Researching and understanding the policy guidance

Before thinking about audiences, initiatives, activities, or messages, the PD section (and, ideally, the mission) should think carefully about this question: “What is the specific U.S. foreign policy goal or interest related to this topic?” It’s important at this stage to research and make connections about the topic to the wider U.S. policy interests and guidance, and determine how PD work on this topic can contribute. A challenging aspect for PD sections is to interpret the U.S. policy goals related to this topic and assess and apply how this guidance relates to their local context.

This challenge presents the first research opportunity for the section to collect and analyze relevant data and evidence. Understanding the U.S. policy guidance to support mission priorities means reviewing:

- Reports published by the Department.

- Cable traffic related to the topic.

- Materials published by the relevant functional bureau.

- Discussions with relevant section or agency representatives in the mission.

- Press guidance from the White House and the Department.

- Relevant meeting notes on the substantive issue.

- Studies from reputable think tanks or academic subject matter experts.

- Bibliographies or references from relevant international governmental organizations (IGOs) or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

(c) Articulating the potential PD contribution

As part of this step, the team will also want to consider the PD contribution, or PD angle, to approaching the relevant topics or issues. There may be important U.S. foreign policy goals and objectives where the PD section is central to the work of the mission, others where public diplomacy plays a supporting role for other sections, and still others where the PD contribution is minimal. Some key questions to ask as you determine the potential PD contribution to a mission priority are:

- To what extent are decision makers in country X responsive to public opinion on this issue?

- To what extent are publics influential in changing conditions on the ground related to this issue?

- To what extent do foreign public attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors affect traditional U.S. diplomatic relations in country X?

- How do foreign public audience attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors in country X directly support or affect the attainment of U.S. foreign policy objectives?

- How can public diplomacy, that is, government or government-sponsored engagement with a foreign public audience, shape the policymaking space in country X?

2. Step two: Current environment – What is going on right now?

This question leads the team into an exercise intended to help you understand the current environment. All PD initiatives occur within a context, and that context influences the methods and outcomes of a PD initiative.

In conducting a thorough analysis of the environment, you also will be laying critical groundwork for a deep dive into analyzing and understanding audiences. People will necessarily be at the center of a depiction of the PD environment because the intent of public diplomacy is to achieve policy results by engaging with foreign publics as audiences. By centering people in your assessment and understanding the contexts in which they are living and working, you will be well-positioned to segment audiences appropriately in your planning and to identify the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors you wish to influence. Audience analysis is the process of using evidence to determine which priority audiences’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to get to the desired PD environment. For more information on that process and how to use evidence to inform your decision making, you can check out Section G. Audience analysis: Using data to inform decision making.

(a) Identify potential audience groups

Based on the current environment, you can consider all of the potential groups you could target within this environment. In this step, don’t worry about precisions. Rather, the goal is to map out and consider the realm of possibilities. The following questions will help guide you as you brainstorm these potential audiences. To answer these questions, you will need to make some assumptions, or best guesses, about potential audiences. See the next section for more information on how to use evidence to test these assumptions.

- Who are the individuals or groups most affected by this issue? What do we know about them? What do affected individuals know about the issue? What opinions and beliefs do they hold? What behaviors related to the issue do they engage in?

- Who are the people who are influential on this issue? What do we know about them? What do influential individuals know about the issue? What opinions and beliefs do they hold? What behaviors related to the issue do they engage in?

- For issues on which PD aims to influence leaders’ decision-making, pinpoint the outcomes that you want to see: changes in voting behavior within the legislative branch, changes in government bureaucratic processes, a new law passed, or a new regulation put in place, etc., and map out how these processes work.

- Work to understand how PD can amplify and empower publics to shape the decision-making environment and the information environment of their governments.

- What institutions and organizations are involved in this issue? How are they involved?

- What attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors do we want to change (or reinforce) on this issue? Who exhibits these attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors?

- Are there demographic or psychographic factors that affect people’s attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors on this issue?

- Where is there conflict between stakeholders, those affected, influential voices, and actors in the space?

(b) Visualize the current environment

With a brainstormed list of influential and affected audience groups, the next goal is to make a visual representation of the current operating environment. With your team (and, ideally, with others in your mission), you will work on mapping the environment, including the people you identified as influential or affected, placing them in the relevant social, political, economic, or cultural context and in relation to one another. The level of effort you spend on the visualization can and should vary depending on: the complexity of the topic; how new the efforts/program/intervention is (that is, how much of a standing basis of evidence you have); how much money you're going to spend on the project itself; and how strategically relevant it is. Consider each of those items and determine how much time and how many resources you need to spend on preliminary research and visual mapping. Broadly speaking, “desk research” is an exercise in deep description and analysis aimed at gathering the following information:

- The issue (challenge/opportunity), its severity, and its causes.

- The people affected by the issue and people who are influential in affecting a solution, and the networks that connect them.

- The broader context (e.g., political, economic, sociocultural, technological, and geographic) in which the problem exists.

- Factors inhibiting or facilitating priority audience behavior change.

Some other questions will help you fill out the context in which potential PD audiences operate. Also ask (and answer, through research) questions such as the following:

- Why has this situation developed?

- What are the relevant legal, legislative, or regulatory processes related to this issue?

- What are the relevant political aspects of this issue?

- What are the relevant economic aspects of this issue?

- What are the relevant social and cultural aspects of this issue?

- What are the relevant technological aspects of this issue?

- What are the relevant geographical or spatial aspects of this issue?

- What are the relevant sources of information about this issue?

- What capabilities and resources do we have at our disposal to use?

- Are other U.S. government agencies, Department of State offices, or other NGO/IGO actors working on this issue?

Be as specific as possible, and link elements together. This understanding of the environment requires more than simply brainstorming a list of stakeholders. Your goal here is to draw a (literal, if abstract or representational) picture or map of the way things work. The key is to identify relevant aspects of the environment as it relates to public diplomacy. In conducting this mapping exercise, consider the following: How are people, organizations, and institutions related? Who influences whom? What are the sources of information (and disinformation) that exist on the issue and who pays attention to which ones?

Importantly, all these questions are empirical. That is, they are not purely theoretical or abstract; they are subject to observation and to being confirmed using research and data. Answering these questions requires conducting research that goes beyond hunches, intuition, and folklore. LE staff are a critical source of information because their knowledge may be highly specific and localized to their experience and perspectives. In addition to consulting LE staff and other American colleagues in the mission, be sure to consult reliable external sources of information to answer these questions as specifically as possible. In some cases, sections will need to commission studies, conduct interviews, or commission a survey or poll (and set aside the resources required to do so). PD sections should think proactively about how to allocate resources toward such research, including by discerning which Washington-based resources can be used or applied. It is insufficient to conclude that these things are ephemeral or intangible. Your goal in this phase is to make what seems abstract concrete.

3. Step three: Future environment – What do we want things to look like when we are done?

This step is another exercise to help you understand the environment; but this time, the goal is to visualize the environment as you want it to be in the future. What will this same issue set look like if we achieve our objective? Whereas the second phase of this process was empirically driven, this third phase is more open to creativity and interpretation. It asks you to imagine a future world, and then, as before, to make your descriptions of that world as concrete as possible by visualizing it in graphical and narrative form. In this step, you establish outcomes and conditions that, if achieved, will indicate that you have achieved your objective. In other words, this phase asks the questions: “How will you know whether you’re making progress toward your goal?” and “How will you know you have succeeded?”

(a) Visualize the future environment

One exercise for this step is to take your visualization or narrative from Step 2: Current environment and to identify explicitly what changes are required to reach Step 3: Future environment. In your visual map, what new nodes need to be added and which should be removed? What associations need to be disrupted, strengthened, or created? What processes need to be changed? What specific attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors, if changed, would most help to move the situation from the current state to the future desired state?

Some additional questions to ask in this phase of defining the future state include:

- What will be typical behaviors, statements, and attitudes of the people involved in this issue? What will the individuals and groups depicted in the desired state think, say, and do?

- What elements of the current environment do we want to preserve? That is, what do we want to make sure does not change?

- How will networks and relationships between people and institutions have changed?

- What legal or regulatory aspects might be changed in the desired state?

- How has the political, social, or cultural landscape changed in the desired state, and what are the indicators you will use to know these things have changed?

- Are there new groups, stakeholders, or actors that have emerged as being more important (or who have diminished in importance) in the desired state?

These questions should point you and your team back to the relevant ICS sub-objective. The level of specificity here is important because, quite often, U.S. policy goals, especially at the strategic level, are abstract and lofty. For example, in the Joint Strategic Plan FY 2018–2022, the first goal was to “Protect America’s Security at Home and Abroad,” and even mission objectives in an ICS might include things like “counter transnational crime.” The loftiness of these goals is one reason that the PDIP requires that initiatives be designed and attached to ICS sub-objectives. Even at the sub-objective level, the PD section may need to narrow the scope of its work to a particular contributing factor or component part of the sub-objective.

In this phase, you want to begin thinking about identifying conditions that will signal successful attainment of (or progress toward) an objective. To determine conditions for the desired future environment, think about the following question: what are the qualitative characteristics that define the desired end state? For example, if the desired end state is more accessible education, some conditions may be the level of technology used in the classroom, or more one-on-one time between students and teachers.

As you identify conditions that would signal progress or success you will also want to think about time. It is unlikely that PD objectives will be achieved all at once, or completely. It is more likely that you will see incremental progress on some fronts and experience steps backwards on others, and that these things will happen in recursive, nonlinear ways. Think about the future state and conditions in terms of short-, medium-, and long-term results and in terms of prioritizing action: what desired changes in awareness, attitude, or action do you see as most acute or as affecting your future work? For example, you might design programs to mitigate specific instances of gender-based violence in schools by increasing awareness of existing protections for students before running a campaign that encourages civic engagement around increasing legal protections for minor survivors of gender-based violence.

(b) Identifying priority audiences

As part of this step, you will want to narrow the universe of potential audiences to identifying a priority audience who will be instrumental in advancing the situation from the way it is now to the way you want it to be. This is the group of people whose attitudes or behaviors will need to change in order to achieve your desired future state.

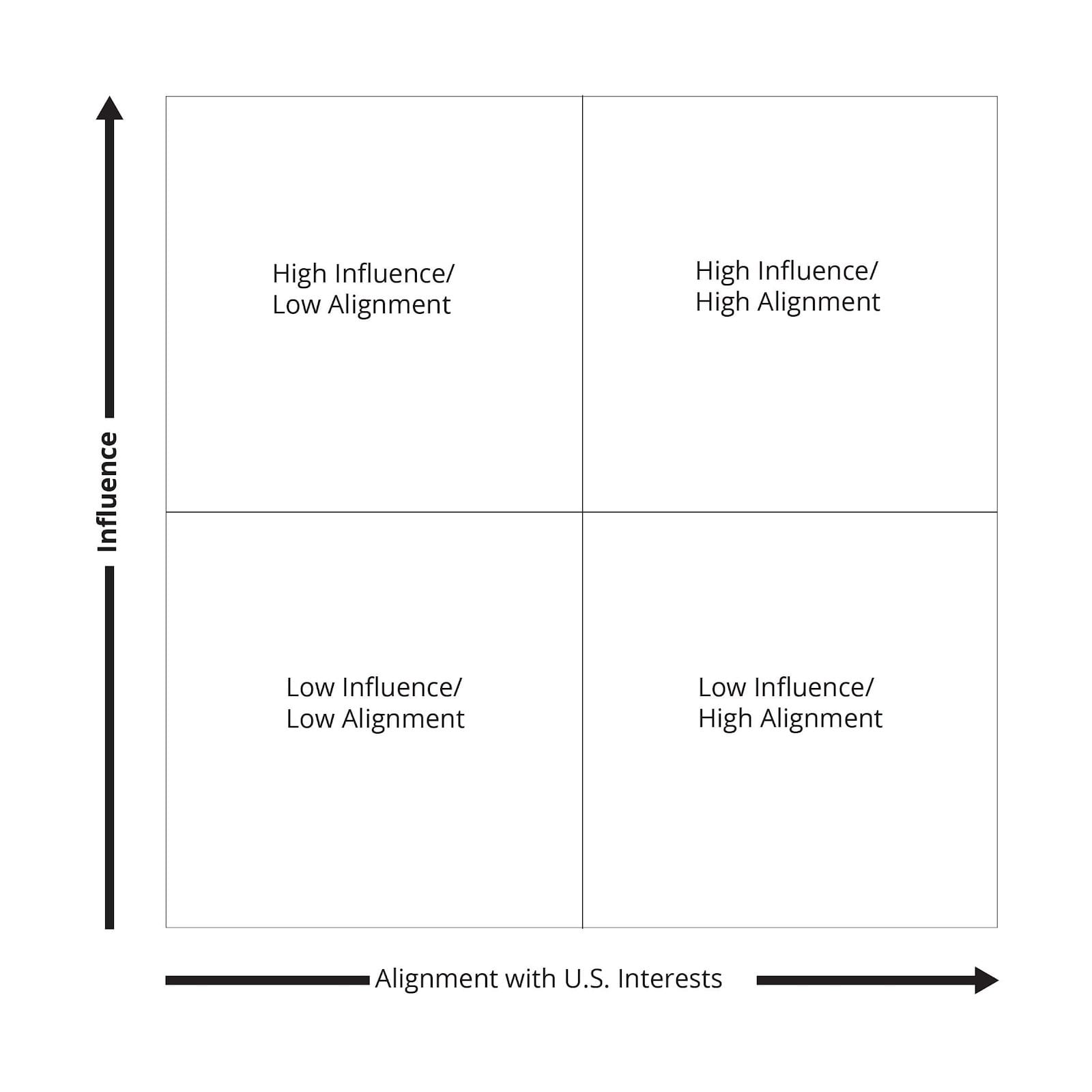

Figure 4. Alignment / Influence Matrix

Because PD resources are limited, this exercise can help your team focus on the priority audience who will be most instrumental in achieving your goals, and design your activity around that group. The number of priority audiences you identify depends on the number of distinct groups whose attitude or behavior will need to change in order to achieve the policy goal. As you explore your potential audiences in order to identify your priority audience, consider the following questions:

- What (and whose) behavior must change?

- How likely is the potential audience to enact the required awareness, attitude, or behavior change?

- Whose attitudes and behaviors could reasonably change because of PD initiatives and activities?

- What audiences provide PD practitioners with the best return for the investment of PD resources, that is, which potential audience groups are reachable and persuadable?

- Which of these audiences is most influential to the post making progress on moving to the desired future environment?

- You can answer this question by thinking about which local audiences have access, influence, and motivation to support the change.

- Consider the benefits for this audience if they enact the change. What do they get out of making the change? Is it something that they should want?

- How are potential audiences aligned (or not) with U.S. policy objectives?

Your initial answers to these questions will help guide your investigation and selection of a priority audience. Whenever possible, corroborate your answers using evidence. This evidence can come from journals, articles, surveys, and more.

Because of limitations regarding resources, access, or political considerations, there may be priority audiences that you identify as important but do not select. One tool that can be useful in selecting priority audiences is the Audience “Alignment/Influence Matrix.” This matrix helps your team chart each potential audience group identified, considering their ability to influence achieving a particular foreign policy goal and their alignment with U.S. goals and values around that goal.

For more information on audience analysis, reference Section G. Audience analysis: using data to inform decision making.

4. Step four: Problem statement – What is the problem we need to solve?

With a deep, visualized, and evidence-driven understanding of the situation, including policy direction, the current environment, and the desired environment, you are ready to analyze the gap between the current and future states, delve into the reasons for that gap, and write a problem statement. A problem statement is a concise description of an issue to be addressed or a condition to be improved upon. It identifies the gap between the current state and the desired state, and it should offer analysis of the problem’s significance and consequences. The problem statement should provide direction about PD’s role in defining the problem, that is, the problem statement should hint at the audience's attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors that represent the obstacle, opportunity, or challenge relevant to the larger situation. This step is important because your framing of the problem will influence how you plan the initiative to solve or mitigate the problem you identify.

Figure 5. Problem statement

In the PD context, a problem statement should be written for an ICS sub-objective that articulates the underlying problem the relevant PD initiatives will address. The ICS sub-objective describes the desired state that your mission wishes to reach. The problem is the gap between the current state and the desired state. Developing a problem statement involves identifying the gap between the current state and the desired state, in addition to identifying the obstacles or challenges that must be overcome in moving from one state of affairs to the other. A strong problem statement succinctly explains both the policy problem in the context of the ICS goal and why addressing this challenge is a mission priority. Even though developing a problem statement should drive you to specificity, it is crucial that PD sections not lose sight of the big picture: PD’s strategic goals, objectives, and outcomes.

Depending on the scope of the problem, the broad problem statement may be broken down into a series of contributing factors. In some cases, these contributing factors may help you determine different lines of effort or initiatives you want to take. Breaking down the problem into its component parts can help you clarify which aspects of the broad problem will be responsive to PD tools and programming and will help you to allocate resources and prioritize your efforts.

For example, an ICS sub-objective may aim to improve opportunities for female entrepreneurs in a given country. The overarching problem is that female entrepreneurs lack opportunity to start and grow their businesses; however, there are component issues that contribute to this problem, these are the challenges or obstacles you want to identify. These obstacles might include some or all of the following (again, this is an opportunity for the PD team to conduct empirical research, don’t guess or rely on intuition): prevailing gender norms, lack of investment, low levels of education, an overbearing regulatory environment, etc. It is unlikely that a single PD initiative can effectively address the entire scope of issues that would-be female entrepreneurs face. Therefore, PD planners should consider the component parts of the issue and focus their problem statement on those issues that their sections/offices are best positioned to address.

Templates can be helpful in drafting problem statements because they provide structure and coherence to ensure you are not missing major aspects of problem definition. Different templates may work better for certain kinds of problems: there is not a one-size-fits-all way to write a problem statement. Templates and sample problem statements can be found in Appendix B: Problem statement templates. See Appendix C: Troubleshooting problematic problem statements for guidance on writing difficult problem statements.

Some questions you can ask for this phase of framing the problem include:

- What is the difference between the current environment and the desired future environment?

- Which elements of the current environment must undergo the most significant change to reach the desired future environment?

- What are the obstacles or challenges that will impede or prevent movement from the current state to the desired future environment?

- What are the component parts of the problem?

- What aspects of the problem is public diplomacy uniquely able or well-positioned to solve?

- What are the opportunities that we see to move things from the current state to the desired future state?

- What are the threats and risks that we might face in trying to implement this change?

To assess your problem statement’s strengths and weaknesses, use this assessment rubric.

5. Step five: The approach – How do we get from here to there?

Your team can now turn to developing an approach to solve the problem. Most complex problems (for which design approach is best suited) will not have just one solution; rather, there are different areas of work or effort that combine to enable you to respond to the problem and deliver you closer to the desired state. This phase of the design process is sometimes referred to as “developing an approach.” Although this phase is still conceptual, the initiatives or lines of effort you lay out here will continue to be implemented in the detailed planning phase. The goal of this step is to imagine a holistic, coordinated approach that will allow you to plan fully and articulate how you will get from one state of affairs to the other.

(a) Selecting and describing priority audiences

Perhaps the most critical element of this phase, for PD professionals, is the selection of clearly defined priority audiences whose attitudes or behaviors will need to change in order to achieve your policy goal. This step is critical to crafting initiatives that are embedded in a strategic framework and have a clear and articulated initiative hypothesis. Priority audiences (which were identified in Step 3, Visualize the Future Environment) are those people whose attitudes and behavior must change for post to achieve its PD objectives. In Step 5, you select which audience group(s) you will aim to reach with PD initiatives and activities. For more on this topic, see Appendix D: Identifying, selecting, and describing audiences. Refer to Section G. Audience Analysis: Using Data to inform decision making for a deeper dive into audience analysis.

(b) Brainstorming initiatives

An initiative is a campaign or group of activities intended to achieve an objective or sub-objective. They are the major building blocks of a mission or section’s PDIP, as they link sets of activities, programs, and messages to a foreign policy outcome. An initiative should house multiple types of activities that all work toward a similar set of outcomes. A single initiative may also target one or more priority audiences, as described above, that should be engaged to further the relevant sub-objective. Multiple initiatives may work toward the same ICS sub-objective and address different aspects of the problem statement. For instance, if one sub-objective is to reduce family violence, the PD section may design an initiative to change public attitudes that domestic violence is a public safety problem rather than an unavoidable family dynamic. Another initiative could be to amplify local leaders' voices who are already working to reduce family violence. A third initiative might be to encourage public support for legislative action to increase penalties for domestic violence convictions, with a focus on six key districts. Each of these initiatives would involve different section activities in support of the initiative. Rather than lumping all of the activities together into one big “domestic violence awareness” campaign, these specific, well-designed initiatives have limited, priority audiences and objectives and outcomes that can be measured and monitored.

One method for developing a PD approach to an ICS sub-objective-level problem statement is to engage your team in a brainstorming exercise. Importantly, brainstorming potential initiatives and activities or programs comes at the end of the design process, after the team has done extensive work to analyze the policy goals, environment, and audiences, and has developed a problem statement. There are typically two approaches for brainstorming initiatives and activities, and the approach may take one or the other, or a mixture of both:

- Brainstorm various activities, and group these activities by each potential initiative; or

- Brainstorm initiatives, and then add various appropriate activities to the initiatives.

It may be tempting to move this brainstorm up in the process, but PD section leaders should resist this urge in order to develop better habits for thinking and planning strategically.

(c) Matching the initiative to your audience

As you brainstorm your initiative, it is important to use what you know about your priority audience to design an initiative that will effectively reach them. Our goal is to design the initiative for the audience, rather than designing the audience for the initiative. When brainstorming, consider the following questions about your audience:

- Whom do they trust? Whom do they not trust?

- Are they comfortable with U.S. messengers? If not, to whom are they more likely to listen?

- Where do they get their information on your policy topic?

- What are their preferred methods of communication?

For more information on how to use research and data to answer these questions, see G. Audience analysis: using data to inform decision making.

(d) Assessing and selecting initiatives

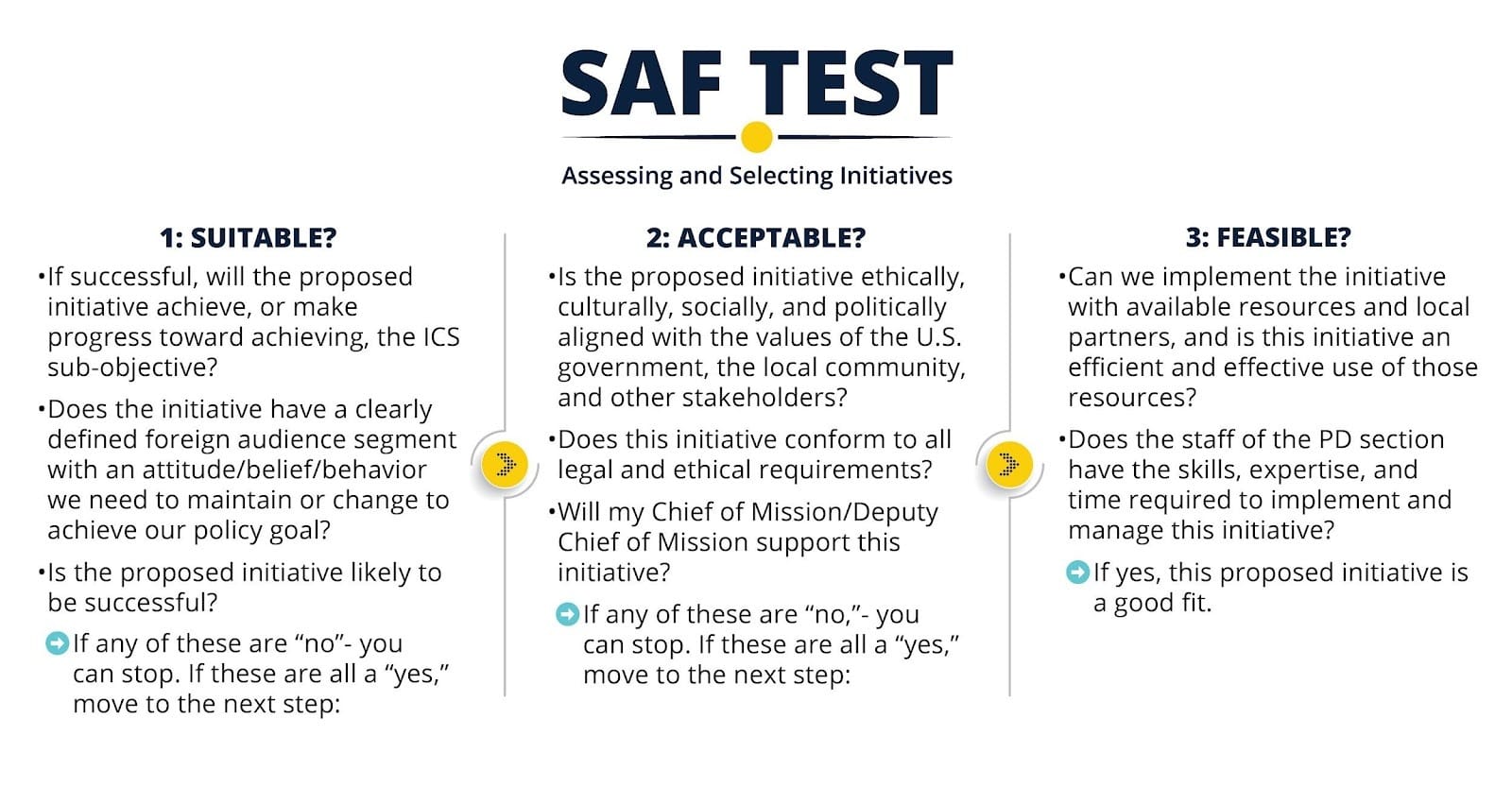

After the brainstorming is complete, and with selected priority audience groups in mind, the team can work to group ideas to form initiatives, and then to narrow down the list by using a Suitability-Acceptability-Feasibility test, or SAF test. In the brainstorming phase, anything goes, as long as there’s an idea for an activity or initiative and a priority audience related to the sub-objective problem statement, the idea goes on the board. Once you have compiled a list of ideas, use the SAF test to analyze them and decide whether they should make their way into the PDIP. For each idea, use the following questions to eliminate potential initiatives (or activities within an initiative) that do not meet all of these criteria.

- Suitability. If successful, will the proposed initiative actually achieve, or make progress toward achieving, the ICS sub-objective?

- Is the proposed initiative clearly related to the relevant problem statement?

- Does the proposed initiative have a clearly defined foreign audience segment with an attitude/belief/behavior we need to maintain or change to achieve our policy goal?

- How likely is the proposed initiative to be successful?

- Acceptability. Is the proposed initiative ethically, culturally, socially, and politically aligned with the values of the U.S. government, the local community, and other stakeholders?

- Will this initiative compete with or complicate other efforts within the mission?

- Will this initiative encounter resistance from important elements of the community? If so, is that resistance a deal-breaker?

- Does this initiative conform to all legal and ethical requirements?

- Will my chief of mission/deputy chief of mission support this initiative?

- Will it be culturally, socially, and politically acceptable to carry out this initiative in my local context?

- Feasibility. Can we implement the initiative with available resources, and is this initiative an efficient and effective use of those resources?

- Does the staff of the PD section have the skills and expertise required to implement and manage this initiative?

- Does the staff have enough time to implement and manage this activity?

- Are local partners available to implement this initiative effectively?

- Will financial or other resource constraints make implementation difficult?

- Does the PD section need to seek additional funding to implement this initiative?

Figure 6. SAF Test

The SAF test should help the PD section critically evaluate how each proposed initiative contributes to attaining the strategic objectives and to prioritizing initiatives to allocate resources effectively.

After selecting priority audience groups and critically reviewing proposed initiatives, a PD section should come away with a concrete list of initiatives that are tied to a specific ICS sub-objective and designed to address a clearly defined problem statement. The initiatives should, together, result in a reasonable chance at making progress toward achieving the desired policy objectives.

6. Iteration and reframing

Although a design approach is deliberative and structured, it is iterative: it starts with observations and uses inference to draw likely conclusions based on them. When new information or observations are added, you should adjust your conclusions.

The environment is constantly changing, partly because of natural reasons like the progression of time, but also because actors, including PD professionals, are actively working to change it. Commonly undertaken when there is a “shift in understanding that leads to a new perspective on the problems or their resolution,” reframing can involve “significantly refining or discarding the hypotheses or models that form the basis of the design concept.”

When doing your design work, think proactively about reframing, what events or indicators might send you back to the drawing board to reassess or modify your approach? Some relevant nudges for reframing might include:

- A major political change (e.g., a national election) in the country

- An unexpected event (e.g., a natural disaster or epidemic) that is affecting the country

- Achieving substantial progress toward an objective (e.g., the host country changes a relevant regulation or policy)

- An unexpected outcome from an initiative or activity (e.g., a program shows higher-than-expected efficacy in moving opinion or behavior)

- A change in the resources available for PD work (e.g., an increase in funding from a new source or the absence of a staff member)

- A change in mission priorities (e.g., your COM asks for specific, sustained focus on an emerging issue)

Using a design approach that is centered in policy objectives and focused on audiences puts into practice the first two pillars of the PD Framework. But the steps and questions here are often useful for collaborative problem-solving at both higher and lower levels; you can use many of the same tools to work with other sections at your mission or bureau to tackle tough, complex problems together, and smaller teams or individuals can use a similar approach to analyzing and designing activities. Remember, the goal is to establish habits of mind that encourage research and evidence-gathering, rigorous analysis, creative problem-solving, deliberate implementation, and constant evaluation and iteration. The process should be people and solution oriented.

G. Audience analysis: using data to inform decision making

Audience analysis helps you reach the right people with the right message in the right way. Alongside sound policy analysis, situation analysis, and drafting a clear problem statement to articulate what needs to change. Audience analysis helps answer the following questions, using data and evidence:

● What is the right priority audience to effect that change?

● What is the right message that will resonate with that priority audience?

● What is the right way to reach the selected priority audience?

Audience analysis is the second element of the PD Framework, and is closely related to the elements “Apply Policy in Context” and “Develop Plans.”

Audience analysis is an evidence-based process to identify, select, and define the groups of people whose attitudes or behaviors need to change in order to achieve a policy objective and to determine effective ways to communicate with and engage these priority audiences. The audience analysis process helps ensure that limited resources are spent on activities that can effect change towards your policy goal. Your audience is actionable when you can 1) reasonably target the group with a single section activity, and 2) reasonably predict how the group will respond or engage with the initiative.

Audience analysis as part of situation analysis: what needs to change?

While audience analysis is a distinct element in the PD Framework, understanding public opinion is crucial throughout the planning process. For example, to write your problem statement, you first need to know the current environment. Public opinion research can help you better understand the current environment so that you can think about what needs to change to achieve the desired future state. Public opinion research may involve such activities as collecting data on the number of people in your country who 1) see a policy topic, like education, as a priority, or 2) do or don’t take a certain action, like voting. Understanding current public opinions before deciding what it is you want to change can help you decide where to invest your valuable time and limited resources to best achieve your desired outcomes.

This section uses an extended fictional example about a PD section working on an ICS goal focused on improving cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreements. However, public support is low in the example to illustrate how a PD section can use public opinion data and audience analysis to help it make data-informed decisions throughout its planning process.

To achieve an ICS goal focused on improving cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreements, you might assume people will be more likely to support the agreement if they understand its implications for improving climate change. However, you decide to check the latest public opinion research and realize that only 8 percent of people in the country list climate change as a top priority. This new information changes your perspective: You now think that the underlying problem might not be that people don’t know about the climate benefits of the agreement, but rather that they don’t see benefits of mitigating climate change as making progress on their higher priorities, like unemployment and health. Your team decides to frame its messaging around the economic and health benefits of the agreement rather than making it directly about climate change.

Once you have identified the current situation and the problem your activity will address, you can move on to figuring out who you need to reach to achieve the change you are looking for.

Who are the right audiences to achieve the change you want to see?

Potential Audience: Once you know what problem you are trying to solve, the next step is to figure out whom you need to reach to achieve your policy goal. After exploring existing data and your team’s observations about the current environment, you may already have some ideas or assumptions about potential audiences who either care about the policy area or might be able to bring about the change you are seeking. A potential audience is a group of people who are affected by or influential on a particular policy or issue. These are the people whose attitudes, knowledge, or behavior you are ultimately looking to change.

Goal: improve cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreement

Problem: people do not connect the effects of climate change to higher priority issues (unemployment and health), so they do not support their government’s cooperation with multilateral climate protection agreements.

Now you think through who is affected by climate-related unemployment and health concerns. While you might say, everyone, or the general public, is affected by climate change, you can narrow this group by considering those whose employment or health are affected by climate change. There may be groups who are unemployed due to changing weather patterns that affect farming. Additionally, you might also consider those who do not have clean water or are suffering from air pollution-related health conditions as affected groups. Or you might want to consider groups that would be most influential in swaying broader public opinion on the agreement, such as trusted economic journalists or business leaders.

There are two important things to note about these potential audiences:

- The audiences identified in this step will likely be far too broad to engage successfully, and there will likely be too many potential audiences for you to engage all of them. You will need to select the potential audience that will be most effective at helping you reach your goal and continue narrowing in to determine your priority audience.

- As you consider potential audiences, you will make a series of assumptions about who is affected by the policy and who can be most influential in achieving your desired policy outcomes. These assumptions are important first steps in the audience analysis process and are key in guiding the direction of your research. However, when possible, it is important to use evidence to confirm or refute these assumptions.

Priority Audience: In order to narrow your potential audience to an actionable priority audience, consider your policy goal and the knowledge, attitude, or behavior that needs to change to achieve that goal (see above). As a reminder, no single activity is going to change the attitudes of everyone in your potential audiences in a predictable way.

A priority audience is an audience that you select for targeted engagement with PD programs, initiatives, messages or other activities. To identify a priority audience whom you can effectively engage, consider the shared knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors that need to change to achieve the policy goal. By focusing your activities on the priority audience who needs to change, your resources will be more effective, and you will be better able to evaluate the outcomes.

Goal: Improve cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreement

Problem: People do not connect the effects of climate change to higher priority issues (i.e. health and unemployment, so they do not support their government’s cooperation with multilateral climate protection agreements)

Potential Audience: People living in areas with decreased air quality and/or limited access to clean water due to climate change

If you want to target people who live in areas where their daily health is affected by climate change, you will need to narrow in on groups whose knowledge, attitudes, or behaviors will need to change in order to improve public demand for cooperation with the multilateral climate protection agreement. To identify these groups, you can look at public opinion data on views of climate, environmental protection, and government action.

For example, you may see an analysis of a recent survey that shows that while only 8 percent of the total population view climate change as a top priority, 65 percent of respondents say that climate-related issues are “somewhat” important for the government to address and only 20 percent say that they are “not at all” important. This tells you that there is a persuadable group out there who does not see climate as a top priority but may still be interested in seeing government action. This is your priority audience, which will be segmented further into a unique and reachable audience.

Audience segmentation: Now that you know your priority audience, you will need to identify what makes this group of people unique by researching the shared characteristics of your audience. In this step, you will use demographic characteristics to better clarify and define your audience. This step is important because it is very difficult to target a group of people based solely on the information in their heads (their knowledge or attitudes) or even on potential future behaviors. However, you can use audience analysis to identify shared demographics of your priority audience that will make them easier to engage. Key demographics often include age, gender, region or location, socioeconomic status, education, and more.

Goal: Improve cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreement

Problem: People do not connect the effects of climate change to higher priority issues (i.e. health and unemployment, so they do not support their government’s cooperation with multilateral climate protection agreements)

Potential Audience: People living in areas with decreased air quality and/or access to clean water due to climate change (urban residents)

Priority Audience: People who think the government should make climate issues at least somewhat of a priority

To better understand the demographics of your priority audience, you could reach out to R/PPR/REU’s Audiences team at Audiences@state.gov to get support in further analyzing any demographic data that may be available on your priority audience. For example, they may have data that indicates that people who say climate issues are “somewhat” important for the government to address are more likely to be between the ages of 35-50, have at least a secondary education, and live in urban areas.

This demographic information helps you better understand your priority audience and begin to inform your message and medium as you develop plans for your engagement.

What is the right message?

Once you have identified your priority audience segment, you need to determine the right message that will engage them and affect change. Your message is the idea you are trying to convey to your audience. It could look like the theme of a program, the script for a television spot, or the talking points in a speech. As you craft your message, you should consider the problem you identified, what you want your priority audience to say, think, or do (the goal of your message), and the shared characteristics of your priority audience segment.

By using your priority audience to inform your message, you are more likely to affect the change you desire in this group. You may have a solid understanding of what messages will resonate with your priority audience from your analysis or you may need to perform additional analysis with this sub-group to understand which messages will best resonate. Message testing is a great tool for this analysis and can be done as a part of audience research, such as surveys or focus groups.

Goal: Improve cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreement

Problem: People do not connect the effects of climate change to higher priority issues (i.e. health and unemployment, so they do not support their government’s cooperation with multilateral climate protection agreements)

Potential Audience: People living in areas with decreased air quality and/or access to clean water due to climate change (urban residents)

Priority Audience: People who think the government should make climate issues at least somewhat of a priority (Ages 35-50, have a higher education, and live in urban areas)

Based on your analysis, you know that your priority audience is more concerned about health than they are about climate change. You also know that they already expect their government to take action on climate issues. This information can help you craft a message that focuses on the health benefits of cooperating with the multilateral climate protection agreement and gives information on how your priority audience can demand further cooperation from their government.

What is the right way to reach your audience?

Once you have identified your priority audience, you need to determine how to reach them. A medium is a communication tool that connects the intended message with the intended audience. This could come in many forms, such as a conference that you host, a radio advertisement, or a social media post. You can utilize data on media usage to better understand how your priority audience gets their information. Once you know where they consume information, you can create a plan to distribute your message on that medium.

In addition, information on whom your priority audience trusts or looks to for this type of information can help you better understand who should deliver your message. At this point, you may want to consider the messengers who are influential to your audience or in your policy areas. These groups may be key messengers as you plan your medium.

Goal: Improve cooperation on multilateral climate protection agreement

Problem: People do not connect the effects of climate change to higher priority issues (i.e. health and unemployment, so they do not support their government’s cooperation with multilateral climate protection agreements)

Potential Audience: People living in areas with decreased air quality and/or access to clean water due to climate change (urban residents)

Priority Audience: People who think the government should make climate issues at least somewhat of a priority (Ages 35-50, have a higher education, and urban)

Message: Potential health benefits of cooperating with the multilateral climate protection agreement and ways the priority audience can demand further cooperation from their government.

As you dig into the data, you find that educated, urban residents between the ages of 35-50 tend to get their news and information from the TV or radio and particularly trust a couple of key outlets.

Alternatively, it is possible that at this point you realize that you are not able to communicate directly with your selected audience. You may not have access to the platforms they use, or they may not trust U.S. messaging and sources. This is when you should consider who may be influential to your audience. It may be more feasible given your resources to target those influential groups.

Given that our priority audience tends to get their information from a couple of key trusted news outlets, you may decide to develop a program to discuss the importance of covering the economic impact of climate change for urban communities with journalists from those key outlets.

The goal of audience analysis is to help you make evidence-based decisions about how you use limited resources effectively. By taking time to answer some key questions about your audience as you determine the policy context and develop activity plans, you can be more confident that your PD activities are affecting the change you need to achieve your policy objectives.

Although this information is presented linearly for simplicity, it is important to keep in mind that audience research is rarely a linear process. As you learn more about your audience(s), you are likely going to want to adjust the plans you set in previous steps. Specifically, this is where further segmentation and identification of the specific changes you want to see within the audience(s) is important.

Bias in data

During this process, data and desk research can uncover previously undiscovered biases among your staff, and they allow you to plan programming that takes these experiences into account. Department and local regulations may prevent specific demographic information from being collected. However, to address this challenge, start by identifying gaps in the human resource systems by determining what information is available and what information is desired. By working with human resources and legal advisors, team leaders can ensure they are capturing the right data while allowing people to opt-in appropriately. Validate information by actively engaging in conversations with members of key audiences. Seeking external confirmation from populations of interest ensures that goals will be met most effectively. Additional outreach efforts can include contacting other organizations whose efforts in the region have been successful with successful efforts in the region, holding focus groups, or connecting with contacts during representation events or alumni reunions. Contacts are likely to appreciate your efforts to better understand their country, context, and people.

H. The Public Diplomacy Implementation Plan process

The Public Diplomacy Implementation Plan (PDIP) process helps PD professionals move from strategy to tactics. It provides a clear plan and common vision for a PD section or PD office, ensuring that all PD activities are organized under initiatives that directly support foreign policy goals. The PDIP is more of a planning process, regularly updated, than a fixed plan.

The PDIP process is documented in PD Tools, a platform for planning, budgeting, analysis, and reporting. It serves as an active planning tool for missions and functional bureaus and illustrates the alignment of resources and activities that advance policy goals. The specific requirements and fields in PD Tools change based on new guidance and user needs, so specific details on using this platform are not included here.

The PDIP process helps posts:

- Explain the problems PD initiatives and activities aim to solve.

- Show leadership the impact of PD programs in advancing mission/bureau goals, objectives, and sub-objectives.

- Increase organizational effectiveness by unifying the PD team and the mission around a common strategic vision.

- Strengthen justifications for PD funding.

- Provide Washington with data to demonstrate results to external stakeholders such as the OMB and Congress.

- Ensure the adequate allocation of resources.

- Set objectives and indicators for monitoring and evaluation.

- Align social media strategy, communications, and programming efforts.

- Guide decision making about new PD efforts, helping prioritize initiatives that align with strategic goals.

- Align leadership support behind PD priorities and help leadership understand the trade-offs involved by taking on nonpriority activities that aren’t included in the leadership-approved PDIP process.

- Update their plans regularly to reflect current priorities and changes in the environment.

- Create a framework and tool to coordinate across the interagency, where various parts of the government, such as the Department of State, the Department of Defense, and other federal agencies, work together to achieve common goals and ensure that their efforts are aligned and effective.

Through the PDIP process, PD sections (at missions) and PD offices (in functional bureaus) analyze the policy context, stakeholder relationships, and opportunities and challenges related to achieving foreign policy goals. They describe the problems that hinder U.S. goals and identify key audiences, resources, and a coherent plan to effect change. The PDIP process has three main components: an overview statement, initiatives, and section activities (which include budget information).

- The overview statement explains the PD section’s or office’s strategic thinking and how PD will advance policy objectives.

- An initiative is a campaign or group of activities intended to achieve an objective or sub-objective. Initiatives are the major building blocks of a mission or section’s PDIP, as they link sets of activities, programs, and messages to a foreign policy outcome. They are collections of related section activities that work together to achieve an ICS or FBS sub-objective.

- Section activities are programs, events, or projects, including messaging and digital outreach, that contribute directly to achieving goals of their parent initiative. They should be updated throughout the year.

The initial PDIP is not an exhaustive list of all activities, but an overview of how the PD team will support foreign policy goals. Once approved, section activities can be added in support of initiatives throughout the year. Any activity using significant funds or staff time should be entered as a section activity.