PD In Practice: Section V -Assessing, learning, and adapting

A. Introduction

The final element of the PD Framework is Learn and Adapt. But it is not the last step, and you cannot wait until the “end” of a program or project to think about how you will assess it and learn from it. In fact, learning and adapting are integral to all parts of the design and planning process, and they are key to improving future PD initiatives. We monitor PD programs to understand what happened and why. We learn by evaluating whether PD initiatives and activities are achieving their outcomes. We rely on data to adjust and shape future efforts. Throughout this process, we communicate what we are learning and how we are adapting.

Although monitoring and evaluation, often said in the same breath, complement each other, they are conceptually and operationally distinct. Monitoring is a continuous process of collecting and reviewing data; it tells us what happened. Evaluation is a systematic and objective assessment of an ongoing or completed activity, project, program, or policy. Evaluation goes beyond what immediately happened in an effort to understand larger processes or outcomes. Assessing our work through monitoring, evaluating, and learning is important because it enables us to:

- understand whether our efforts are resulting in our desired outcomes

- determine whether the efforts should continue and whether we should continue with specific activities

- inform efforts to refine and improve how we design our PD programs

Furthermore, a robust commitment by PD practitioners to the principles of learning and adapting also:

- ensures PD insights can be used to inform the formulation and execution of U.S. foreign policy

- furthers the PD community’s goal to share best practices and lessons learned to improve the practice of public diplomacy in the field

- enhances the reputation of PD practitioners as serious contributors to policy

- assesses the extent to which public diplomacy can be used to advance policy objectives in local contexts

Committing to these principles, though, is challenging. When planning and executing activities and initiatives, it might be tempting to postpone thinking about M&E until the end; but waiting often results in not having access to the necessary data or resources needed for the answers we are seeking. Once an initiative or activity is finished, it can be very tempting to just move on to the next thing, rather than taking the time to reflect, learn, and adapt.

These impulses, however strong, must be ignored for several reasons. First, although each event, activity, or initiative may be unique, there are many PD projects and approaches that are similar from year to year. Second, rigorous reflection and evaluation will set you up for better planning in the next cycle, as you will have captured new information about the environment, your audiences, various parts of the logic model, the extent to which your activity achieved its expected outputs and outcomes, and how your work helped advance U.S. foreign policy objectives. Third, establishing good habits, routines, and mechanisms for recording and sharing best practices and lessons learned (among other things) will facilitate better collaboration across PD sections and ensure continuity when PD professionals move from post to post. Finally, thoughtful analysis of evidence and data should inform the development of policy (which brings us full circle, back to the first element of the PD Framework: Apply Policy in Context). When we continue to evaluate, learn, and adapt, PD interventions improve. All PD teams should analyze data and evidence to gain valuable insight into ongoing progress and projected future results that could affect implementation.

Establishing clear and consistent procedures for closing out projects (initiatives and activities) can assist your PD section in improving its internal processes and management, decision-making and strategic planning, organizational knowledge, operations continuity, and resource allocation.

B. What is monitoring and why is it important?

Monitoring is a continuous process of collecting and reviewing data to measure what is happening during a program. Monitoring also focuses on whether a program is meeting its measurable performance standards as outlined in the project plan. While 18 FAM 300 permits monitoring at both the program and project levels, and it is possible to monitor PD at both initiative and section activity levels, this guidance (and the PD Monitoring Toolkit) recommends prioritizing monitoring at the section activity level. This level represents a specific intervention designed for a targeted audience, with clearly defined expected outcomes. Monitoring initiatives may be appropriate when the associated section activities target the same audience segment and share a unified set of outputs and outcomes.

Monitoring can describe what happened during initiative or activity implementation and often focuses on basic descriptive output data, that is, on answering factual questions about who, what, when, and where. Monitoring data can indicate when an evaluation is needed to understand how or why certain results are being observed, and it can provide useful inputs into planning or conducting an evaluation. Monitoring can assist also in describing environmental and audience conditions, which in turn can inform program design and implementation decisions.

Public diplomacy employs two types of monitoring: accountability monitoring and performance monitoring.

- Accountability monitoring, sometimes referred to colloquially as grants monitoring, is collecting basic program or administrative process information to ensure that activities occur according to plan and resources are accounted for. This level of monitoring should be maintained for all activities, and it is a requirement for grants.

- Performance monitoring is the systematic collection of data that measures conditions important to program design and management. Typically, these conditions are compared against established goals or targets. Data from a performance monitoring system describes what is happening across an activity or group of activities to identify questions that warrant further study through more resource-intensive evaluations. This data can be used to initiate course correction and inform decision-making throughout the implementation period. Performance monitoring won’t offer conclusive explanations about how or why certain patterns are observed; however, the data can be used to conduct further evaluations. Monitoring complements evaluation by ensuring that future evaluation resources are focused on assessing the most critical questions or aspects of programming.

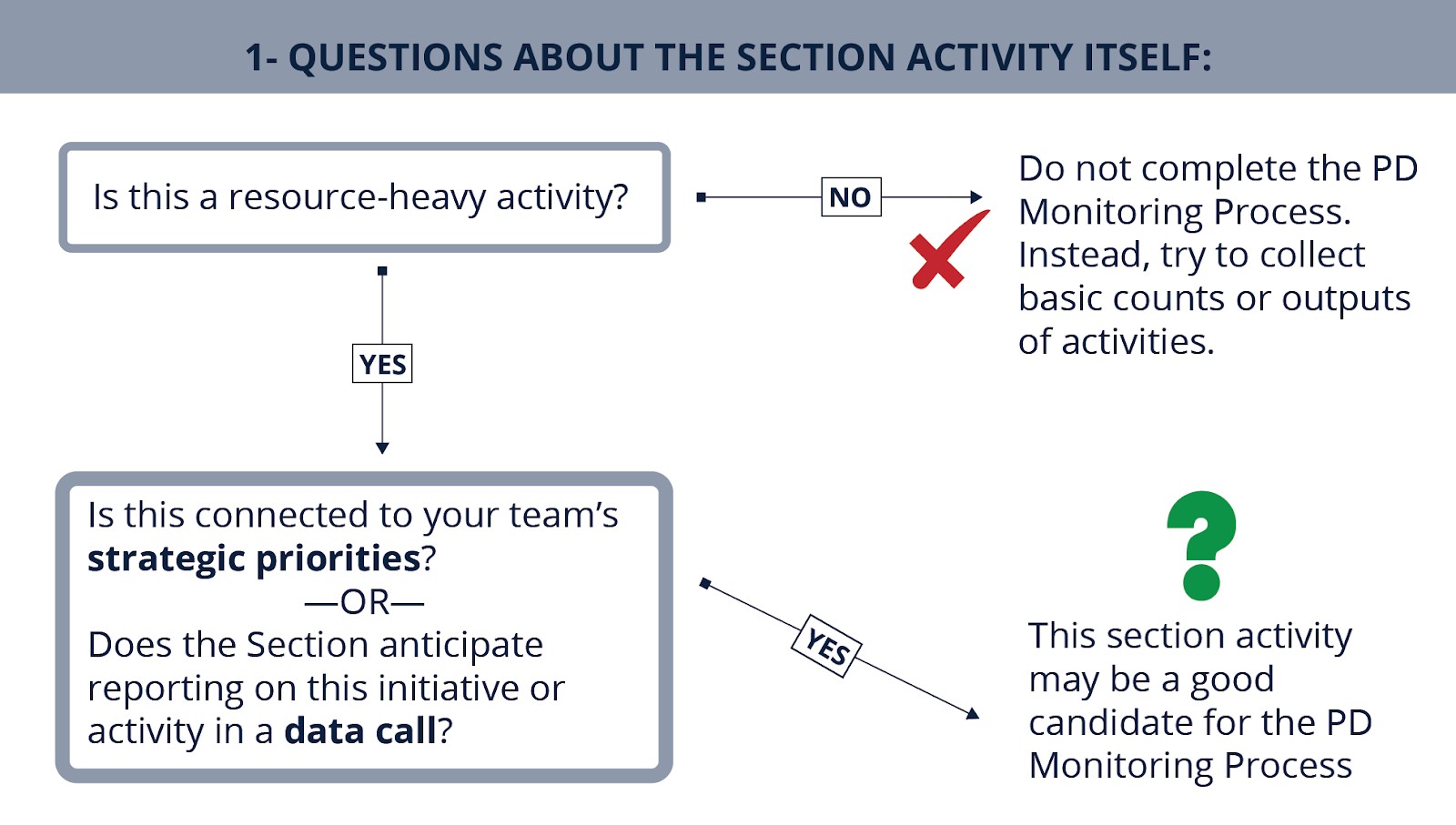

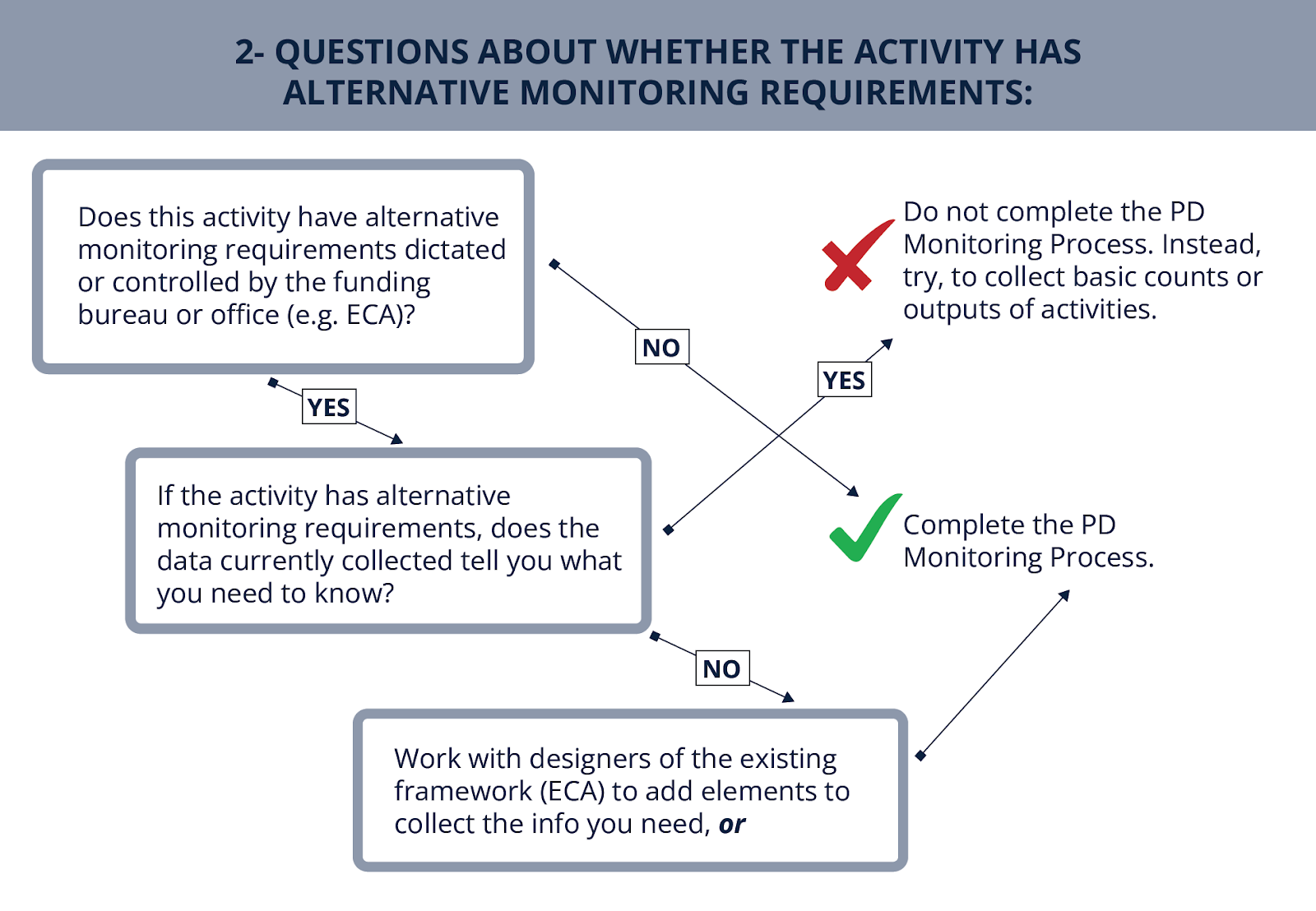

PD sections cannot monitor everything, and it would be inefficient to attempt to do so. Instead, determine what your section will monitor by considering how closely it aligns with your team’s strategic priorities, whether it is relatively resource-intensive, the likelihood of it being included in a data call, and the extent to which it is already covered by other monitoring requirements (e.g., those funded by bureaus such as ECA or DRL). Figures 11 and 12 provide guidance on the questions you can work through with your team when deciding on whether an activity is a good candidate for the PD Monitoring Process.

Figure 11.

Figure 12.

When the responsibility for establishing the goals, objectives, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of programs or projects is held solely at post, the responsibility for executing the requirements of the Department’s policy guidance on M&E described in 18 FAM 300 rests with post staff, in consultation with the appropriate functional or regional bureau.

C. Making a plan for monitoring and evaluation

Incorporating monitoring and evaluation should be part of the full program lifecycle, and in public diplomacy, M&E should be part of the culture of PD sections’ work. From identifying audiences and planning strategically, to drafting program objectives and indicators, as well as collecting monitoring data, each team member should think about how their contributions to PD interventions contribute to achieving policy objectives and how their responsibilities contribute to the M&E processes, workflow, and attaining leadership buy-in. Embedding M&E in the process from the planning stage allows teams to fully consider what data will be collected and to create a strategy around how they will collectively analyze and learn from the monitoring data. Using data from monitoring and evaluations then helps the team and its leadership inform both processes and outcomes.

This section provides a simple framework for developing a monitoring program within a PD section. Broadly, there is a three-part approach to monitoring PD initiatives and activities: using a logic model, developing a monitoring plan, and completing an after-action review (AAR). More information on each step is available in the PD Monitoring Toolkit, which is also part of PD Foundations. Once a PD intervention (initiative or section activity) has been selected for monitoring (using the monitoring selection criteria, above), the process is as follows:

- A logic model is a visual roadmap that illustrates how PD interventions (section activities or initiatives) lead to changes in the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of priority audience groups, ultimately achieving a defined objective. In PD, resources, audiences, and actions integrate to produce measurable short and long-term outcomes. The logic model serves as a framework for "if-then" reasoning, clearly linking actions to desired results. A well-designed logic model lays the foundation for planning and provides key indicators for the monitoring plan.

- A monitoring plan is a document that outlines how to measure a section activity's outputs and outcomes. It defines progress and success by identifying specific indicators and data collection tools. The plan includes:

- A list of indicators for outputs and outcomes

- Tools for data collection

- Performance targets for each indicator

- Actual values obtained through data collection

It translates the logic model's planning into actionable steps to track implementation progress. Additionally, the monitoring plan supplies essential data for conducting an after-action review.

- An after-action review (AAR) is a structured evaluation of a section activity's results. Using the Monitoring Toolkit, teams follow a structured meeting template to reflect on outcomes, implementation, and next steps. The AAR connects planning and monitoring by analyzing data collected during the monitoring phase to enhance future activities. It creates a space for thoughtful reflection on planning, execution, and overall effectiveness. There are multiple debrief templates included in Appendix H of the Monitoring Toolkit.

D. Evaluations

Evaluation shares some features with monitoring, but the distinctions are important.

- Evaluation: a one-time assessment to determine whether, how, and why a program met its stated goals

- Monitoring: a continuous process of collecting and reviewing data to measure what is happening during a program

Evaluation is intended to facilitate understanding of larger processes or outcomes, asking and answering “how” and “why” questions. The data collected in program monitoring can be useful to tell you when an evaluation is needed, to help you understand why certain results are being observed, and to plan and conduct an evaluation.

Conducting an evaluation of a PD event, activity, or initiative can help you answer questions about the efficacy of your planning and implementation; an evaluation will help you test the hypothesis of your program. Some questions that a formal evaluation might help you answer include:

- Does the link you identified between the audience, their expected/anticipated attitudes/beliefs/behaviors, and the PD initiative hold up to scrutiny?

- Were there confounding circumstances that you didn’t (or couldn’t) account for in planning?

- Did you achieve your program objectives, such as raising awareness about an issue, changing attitudes on an issue, or influencing behavior in a desired direction?

- Is it worth using the same implementing partner next time?

- How could you improve your program?

- Is your priority audience the actual audience that participated in your program?

The Department’s policy guidance on M&E described in 18 FAM 300 recognizes that evaluation is a key element in design and planning, but that not all PD programs require formal evaluation.

1. Do I need a formal evaluation?

Not all PD programs require a formal evaluation. In determining whether one is appropriate, bear in mind that one of the following conditions should be met:

- The program is a large one (e.g., within the top 10 percent of programs in terms of expenses).

- The program is being considered for scaling up.

- A formal evaluation would provide critical information for decision making.

A program does not need to satisfy all of these conditions to qualify for a formal evaluation. Indeed, programs may meet one of these conditions and still not require a formal evaluation. Even though a program may be early in its lifecycle, it might rely on well-established and known mechanisms for effecting change, or be of such small scale that an evaluation may be both unnecessary and impractical.

Sometimes the right decision is to choose not to evaluate. Some circumstances in which a formal evaluation might not be a good use of resources include the following:

- A program has ended without an evaluation plan in place, and a retrospective evaluation is not possible.

- A program will not be repeated.

- The program is not strategically relevant to either the mission or other PD practitioners.

Other considerations when planning to conduct a formal evaluation include how the findings will be used, who will be interested in the findings (stakeholders), and how the data for the evaluation will be protected and accessed. If an evaluation does not have a clear audience or purpose, it may not be worth the risk, cost, and effort. Planners should begin thinking about an evaluation early in the planning cycle, waiting until right before a program launches to plan an evaluation can contribute to a poor evaluation. Thinking about these things before conducting an evaluation will increase the evaluation’s value to individuals and to the organization.

2. Principles of evaluation

When you decide to plan and conduct an evaluation, consider how findings will be used and develop an evaluation dissemination plan that delineates all stakeholders and ensures that potential consumers of the evaluation will have access to evaluation results. For Department-wide guidance, 18 FAM 300 lays out the following principles to consider when planning for an evaluation:

- Usefulness. The information, ideas, and recommendations generated by evaluations should serve the needs of the unit. Evaluations should help the unit improve its management practices and procedures, along with its ongoing activities, by critically examining their functioning and the factors that affect them. Evaluation findings should also be considered when formulating new policies and priorities.

- Methodological rigor. Evaluations should be evidence-based, meaning they should be based on verifiable data and information gathered using the standards of professional evaluation organizations. The data can be both qualitative and quantitative.

- Independence and integrity. Bureaus should ensure that evaluators and other implementing partners are free from any pressure or bureaucratic interference. Independence does not, however, imply isolation from managers. Active engagement of bureau staff and managers, as well as implementing partners, is necessary to conduct monitoring and evaluation, but Department personnel should not interfere with the outcomes.

- Ethics. Department staff and evaluators should follow the accepted ethical standards in dealing with stakeholders, beneficiaries, and other informants. These are:

- Rights of human subjects. When human subjects are involved, evaluations should be designed and conducted in a way that respects and protects their rights and welfare and includes informed consent.

- Sensitivity. Evaluators should be aware of the gender, beliefs, manners, and customs of people and conduct their research in a culturally appropriate fashion.

- Privacy and confidentiality of information. The privacy and confidentiality of information should be maintained. If sensitive information is involved, efforts should be made to ensure that the identity of informants is not disclosed.

- Conflict of interest. Care should be taken to ensure that evaluators have no potential biases or vested interest in the evaluation outcomes. For example, a firm should not be contracted to conduct an evaluation if it played any role in supporting the program's execution or activity being evaluated.

3. Types of evaluations

Four types of evaluation are helpful in determining how or why certain results are being observed: needs assessments, process evaluations, outcome evaluations, and impact evaluations.

- Needs assessments are systematic processes used to discern the gap between current results and desired results. They are often used in attempts to determine the root cause of the gap and compare alternative options to close the difference between current and desired results. Needs assessments answer the question: What is the gap between current and desired results or conditions, and what are the options to close the gap?

- Process evaluations focus on how closely a program’s implementation follows the program’s design to identify strengths and weaknesses or gaps in process. Process evaluations answer the question: Is the project being implemented as designed? Process evaluations can also assess the efficiency and efficacy of internal business processes.

- Outcome evaluations are systematic, evidence-driven assessments focused on questions of progress toward achieving a program’s intended goal. Outcome evaluations demonstrate that a program contributed to the result but may not be the direct cause of that result. Outcome evaluations answer the question: Is the program associated with progress made toward achieving the goal?

- Impact evaluations analyze the causal link between programs and a set of outcomes. They always involve the collection of baseline data for a participant group (treatment) and a nonparticipant group (control), as well as subsequent rounds of data collection after the program. In impact evaluations, control groups are similar across characteristics important to the treatment group. This means that impact evaluations demonstrate the causal link to the results that is attributable to that program alone. Impact evaluations answer the question: Are the outcomes of this project due to the project and not to other factors?

4. Conducting an evaluation

When conducting an evaluation, it is likely that you will want or need to call on the expertise of external evaluators.

In-house resources

Two offices provide direct evaluation support for PD sections interested in conducting an evaluation of one or more of their programs.

- The Research and Evaluation Unit (REU) is part of the Office of Policy, Planning, and Resources (R/PPR). The 2021 PD Modernization Act charges the REU Director with generating new research as well as with coordinating and overseeing the research and evaluation of all PD programs and activities of the Department of State to support the use of evidence-based decision making. The REU team helps posts by conducting original research on PD initiatives, interpreting existing research, and disseminating knowledge tailored to the needs of PD practitioners, including through M&E of PD programs, public opinion polling, bespoke audience research, and applied research on internal R family products and practices.

- The Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs, Office of Press and Public Diplomacy (SCA/PPD) Grants and Programs Office provides direct strategic planning, program design, and program and grants M&E support, along with tailored trainings to PD offices in the SCA region across these three work areas. The team has extensive experience with managing and monitoring large programming grants and contracts and offers support to PD sections in the region to improve their efforts to plan, design, and assess their programs.

Contracted resources

There are also many options for contracting out an evaluation outside the Department. Because of the nature of contracting these services, you will need to have a clear idea of your requirements and funding levels before putting out a call for work or finalizing the contract. Both the REU and the Office of Intelligence and Research/Office of Opinion Research (INR/OPN) can help narrow these ideas and assist in writing a statement of work or provide examples. When contracting out an evaluation, think carefully about what deliverables you seek from a grantee. There are two types of deliverables to request from contracted firms for evaluations: process deliverables and products. Be as prescriptive as you reasonably can when writing research and evaluation grants and contracts. With a contracted evaluation, in every case be clear about which points require embassy approval and subsequent revisions.

- Process deliverables are deliverables that provide updates on how the program and the evaluation are going and may include the following:

- Evaluation proposal: This describes the design of the evaluation and what the evaluation will tell you. It is important because this is your chance as the program office to ensure that the evaluation results are useful to you.

- Midterm reports: These will include a number of surveys, fieldwork challenges, and more as the program and evaluation are implemented.

- Products are the final data, reports, insights, and facilitated learning you wish to gain from the evaluation process. Products should have all the information you need to share results of the program with your stakeholders. Products may include:

- Final reports: Contracted research should write reports that are both rigorous and relevant. They should provide clear answers to the research questions and provide the reader with a reasonable understanding of how those answers were derived. A report should, at a minimum, include a section addressing background, methods, data and analysis, findings, and conclusions.

- Data instruments and data sets: The contracted researchers should provide program planners with both the instruments used to collect evaluation data and cleaned and organized data sets created using those instruments.

- Facilitated learning sessions: At a minimum, a contracted research project should prepare and deliver a presentation of final evaluation results to program planners. This session should summarize the process and findings and allow planners to ask questions, clarify items, and openly discuss the conclusions to encourage organizational learning.

E. Reflecting and debriefing

Learning takes place when a team engages in thoughtful discussion of information with a focus on understanding how and why various aspects of a program, project, or process are progressing. The intent is to look for opportunities to make positive changes, not to place blame or impose penalties. Bureaus and independent offices should regularly discuss available data to determine whether the right data are being collected to inform decisions, or whether ongoing monitoring and/or evaluation plans should be modified to collect information more useful to decision makers. Therefore, holding discussions on surprises arising from the data, sharing positive or negative results, and reflecting on ways to implement activities differently is an invaluable step for improving PD programming. As the PD Tools platform becomes more developed, posts can view PDIPs and monitoring data from other posts and learn from best practices.

In an organizational context, learning means taking the knowledge your team gains from evidence and using it to improve decision-making, create opportunities for continuous improvement, and ensure accountability in your programs. Part of your project planning should, therefore, include convening regular meetings and communications to reflect on M&E findings and adapt your operations accordingly.

Depending on the scope of your project, these communications may involve a variety of stakeholders such as managers, working staff, implementing partner groups, and constituents as appropriate. Best practice is to take an integrated approach to these reflection periods that includes stakeholders at multiple levels of a project, to gain different perspectives.

There are many ways to conduct a project debrief, closeout, hotwash, or after-action review. Deliberative reflection should be part of the closure phase for every project, but this process can also be helpful after the completion of major milestones and deliverables within a project. Several templates for conducting debriefs or after-action reviews are included in Appendix I: Debrief Templates.

To move these reflections toward actions, it is important to adapt your operations by turning your findings into action plans for future activities, projects, and decisions. These, too, should be continually monitored for results. In this sense, we can view M&E as a continuous cycle of improvement.

F. Preparing for a routine OIG inspection

What is a routine OIG inspection? Routine OIG inspections are scheduled inspections that occur no less than every five years. They assess the Department’s operations primarily in three areas set out in the Foreign Service Act of 1980: policy implementation, resource management, and management controls. The inspection also reviews the efficiency and effectiveness of operations and whether operations are consistent with Department regulations and policies.

OIG inspections should be viewed as an opportunity to learn from objective assessors what is working well and where improvements can be made to PD operations. Many reports also include Spotlights on Success, which highlight a mission’s innovative, effective, and replicable practices. During the information-gathering stage, preinspection surveys and questionnaires help determine the inspection's scope and guide the inspection's fieldwork portion.

For overseas inspections, inspectors will interview Department of State direct-hire employees, LE staff, and if applicable, contractors. Additionally, the inspectors will interview country team members, review documents and electronic files, and observe your mission’s activities. The inspection team will try not to disrupt everyday operations, but this will not always be possible since time is limited. Typically, the onsite work lasts between two and eight weeks, depending on the inspection timeline, size of the post, and the scope of the inspection. Inspectors will also interview Washington-based stakeholders such as the regional bureau that oversees the post being inspected, and other domestic bureaus that have staff working at the post.

Instructions for Inspections are posted at the OIG SharePoint site:

G. Communicating what we learn

PD practitioners' work of monitoring, evaluating, reflecting, and learning is most useful when it is recorded and communicated. A best practice is a good work practice or innovation captured, analyzed, and shared to promote repetition and establish a model for implementing a practice or innovation. A lesson learned is a process, experience, or tool captured, analyzed, and shared to overcome obstacles and avoid replicating challenges. Sharing best practices and lessons learned helps develop a more systematic way to capture, analyze, synthesize, and share insights to make data-informed decisions.

A best practice or a lesson learned not recorded or shared is a missed opportunity for increasing institutional knowledge. Both individuals and teams are responsible for documenting and communicating what they have done, learned, and accomplished. These habits cultivate a culture of learning and continuous improvement in the PD community. Effectively collecting, analyzing, and sharing what we know based on evidence enables PD practitioners to:

- Advocate for additional resources and funding

- Allocate existing resources effectively and efficiently

- Prevent repeated mistakes or missteps

- Identify and fill gaps in knowledge and training

- Reduce knowledge loss and knowledge gaps arising from personnel turnover

- Support strategic decision-making and prioritization

There are many options and paths for communication, and each of them serves a different function for a different audience. When choosing how to report and communicate your results, consider the audience you want to reach and the purpose of the communication, just as you would with any PD message or program.

1. Reporting in PD Tools

One part of project management is project closing. PD sections are expected to enter details about section activities as part of this process. Full reporting in PD Tools enables PD practitioners in the field and in Washington to see PD initiatives and activities at different levels of granularity. For example, a PD desk officer could pull a report on all activities completed in a region, or someone in the R/PPR budget office could run a report that accounted for all .7 spending to date on a certain administration priority. PD practitioners could look at the activities and outcomes of another post around a key issue like elections and consult with them about best practices, or see how they had adjusted their programming in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic or after a natural disaster. These types of reports, which improve transparency and communication, are only as good as the data entered into the system. PD Tools’ reporting capabilities will not solve or address all data calls, but the database is a powerful tool for sharing information.

2. Peer networks and communities of practice

The PD community at the Department of State is dynamic and energetic. Foreign service officers move around the world between posts and assignments, and LE staff and civil servants often hone expertise and skills over years. Developing networks and communities of practice within this community is an important part of the Learn and Adapt element of the Framework. Learning from each other is a key part of cultivating a culture of learning. Communities of practice may be formed around any characteristic that people have in common: a job function (e.g., digital diplomacy and social media managers; LE staff supervisors; PAOs); a substantive issue area (e.g., countering disinformation, encouraging entrepreneurship); a region (e.g., West Africa, Central America). Communities of practice and peer learning networks can be formal or informal and are an integral part of the PD community’s efforts to cultivate a culture of learning.

3. Writing cables

Cable writing is the official channel for formal communication in the Department. It is simply part of a diplomat’s job. Cables are information currency in the Department, and they inform and shape policy in important ways. For example, cables can play a crucial role in officially conveying the ambassador’s view about what works and what doesn’t in their country. Monitoring and contributing to cable traffic keeps officers and offices apprised of emerging and evolving situations around the world. Cables prompt action and responses. Well-written cables can gain traction and attention in the Department and the interagency; therefore, it is important that cables represent and communicate honest and nuanced assessments of PD work.

For PD professionals in the field, there are four primary types of cables, described below, that help communicate and situate PD work within a broader context.

- Informing and shaping policy. These types of cables focus on the ways that foreign publics are affecting the policy-making environment in which a specific strategic objective is being pursued. A policy-shaping cable may analyze how a policy or message might be perceived by a foreign public audience, or it could explore potential interactions between foreign publics and U.S. government interests. A policy-shaping cable may focus on a particular group or objective.

- Reporting. These types of cables may focus on an event or program and answer the question, “What happened?” and, more importantly, “Why does it matter?” These cables may have varied audiences. For example, ECA or R/PPR may be interested in a report on some of the programs they funded, or the cable can help amplify a post’s work for an under secretary or other appointee. These cables should always be linked to policy objectives and articulate how the program advanced U.S. interests, and, if the program did not achieve its desired results, offer an analysis of why it didn’t. Whenever possible, reporting cables should include concrete quantitative data to support the claim about influence and effectiveness, in addition to providing qualitative evidence through anecdotes and narrative.

- Audience and situation analysis. These types of cables analyze how the PD section is moving forward with raising awareness; changing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors; and shaping decision-making and policy environments, especially in relation to specific U.S. foreign policy priorities and objectives. What are the trends in media (traditional and digital), networks, and social listening that are shaping how posts plan and implement PD initiatives and activities? What factors influence public opinion regarding a certain policy area? What are the drivers of mis- and dis-information in the country?

- Best practices and lessons learned. These types of cables enable the programmatic collection, analysis, and distribution of materials related to best practices and lessons learned. Best practices and lessons learned cables help organize, share, and recognize the excellent work of practitioners. Collecting this information systematically provides grassroots input for the practice of PD and informs future guidance. Sharing best practices and lessons learned promotes the efficient use of resources and funding, prevents common mistakes, helps people work smarter and more efficiently, and identifies and fills knowledge gaps. This reduction in knowledge transfer time and loss of know-how, enables strategic decision-making and promotes a culture of learning and innovation. Best practices and lessons learned cables should be tagged with the KLRN cables tag in SMART. Resources, including cable templates and samples, can be found on the Best Practices and Lessons Learned page on PD@State.

Writing and clearing cables takes substantial time and effort. That’s why missions develop quarterly reporting plans. Consider taking a proactive strategic planning approach that factors in the time and effort necessary to craft a good cable. To best align incentives and motivations, consider when a cable about public diplomacy might be most effective. Because cables are part of the institution’s enduring archive and institutional memory, two situations are particularly suited for writing PD-related cables:

- When something is innovative, new, or different. Cables that highlight a change or innovation invite a continuing conversation about the future. Cables that focus on changing context and highlighting new information also allow other practitioners around the world to think proactively about adopting or adapting ideas and methods in their own context.

- When something is surprising. Cables that focus on the unexpected, surprises, mistakes, or misfires can be tremendously important tools for assessment and learning. These types of cables involve some level of risk-taking, as it can be uncomfortable to admit to and assess undesirable results; but if the focus is on learning and adaptation, the opportunity for growth and improvement is unmistakable.

Tips for effective cable writing about public diplomacy include the following:

- Write about why and how. Think of cable writing as an opportunity to make an argument and to answer analytical questions. Move beyond a litany of answers to “who, what, when, where,” and think about answering questions that begin with “why” and “how.” Why did the PD section design the initiative in this way? How did the activity advance a U.S. policy objective in a meaningful way? Cables about PD programs that are written after an initiative or activity has closed out can sometimes seem like an exercise in celebratory show-and-tell. Shifting to an analytical mindset enables PD sections to make arguments about why their work is important and how others might adopt or adapt similar ideas.

- Think about your audience and invite conversation. After some practice implementing the PD Framework, this idea should become second nature for PD practitioners. Whom would you like to read your cable? What information and context do they need to make sense of what you are sending and for it to stand out in a veritable flood of cables? What would you like that person to do after reading it? Consider that many busy policymakers might not read past the opening paragraph. What are the most essential items you want to convey to this audience?

- Plan your cable-writing approach. Perhaps there are specific areas you want to focus on for the year, or perhaps there are certain kinds of cables that should be written routinely. What are your section’s priorities and goals? What are the policy priorities where foreign publics are particularly important and influential? What audiences and publics does the PD section interact with on a regular basis, and how might those interactions contribute insight and analysis on topics such as press freedom, academic freedom, civil society development, human rights, and good governance? PD sections should be thinking about cable writing in concert with other parts of the mission’s reporting plans.

- Draft in partnership with other sections of the mission. Through strategic design, PD sections should work across the mission in planning to achieve policy outcomes. Drafting cables in partnership with political, economic, or other mission sections or elements is also a good way to convey the centrality of PD to mission efforts toward advancing policy priorities and achieving policy goals. PD sections should be involved in mission reporting plans and priorities, and PD sections should clear on other sections’ cables as well.

- Work with your regional PD office and PD desk officer. Working in concert with others can help your section determine what kinds of cables to write, whom they are for, and how to make them effective. Seek feedback and communication about their needs and your needs. Know your post’s reporting priorities and consider how your reporting can contribute to and/or complement other sections’ cables. Can your PD perspective influence imminent policy decisions? Can your PD insights help ensure Washington is funding the right initiatives the right way and that they are directed to the right audiences?