PD In Practice: Section IV - Implementing and Managing

A. Introduction

Once plans are in place, it is time to implement, manage, and monitor initiatives, activities, and events. As in the planning phase, many tools are available to assist with executing and implementing programs successfully. This section drills down on processes related to the fourth element of the PD Framework: Manage Effectively. It includes several introductory sections on team management, project management, financial management, and knowledge management. Just as with any policy topic, strategic planning, audience analysis, or monitoring and evaluation, all of these areas involve complex systems and processes that take years of study and practice to truly master, but when PD practitioners and teams have a common baseline vocabulary and understanding of core principles, it facilitates collaboration, teamwork, and effective work practices.

B. Managing the PD team

The success of PD initiatives and activities is dependent on the expertise and experience of many PD practitioners. This section focuses on a key aspect that is critical for managing an effective, modernized PD section: managing cross-functional teams. Even an abundance of financial and physical resources cannot overcome gaps in human capacity, innovation, creativity, and collaborative effort in a PD section.

1. Cross-functional teams

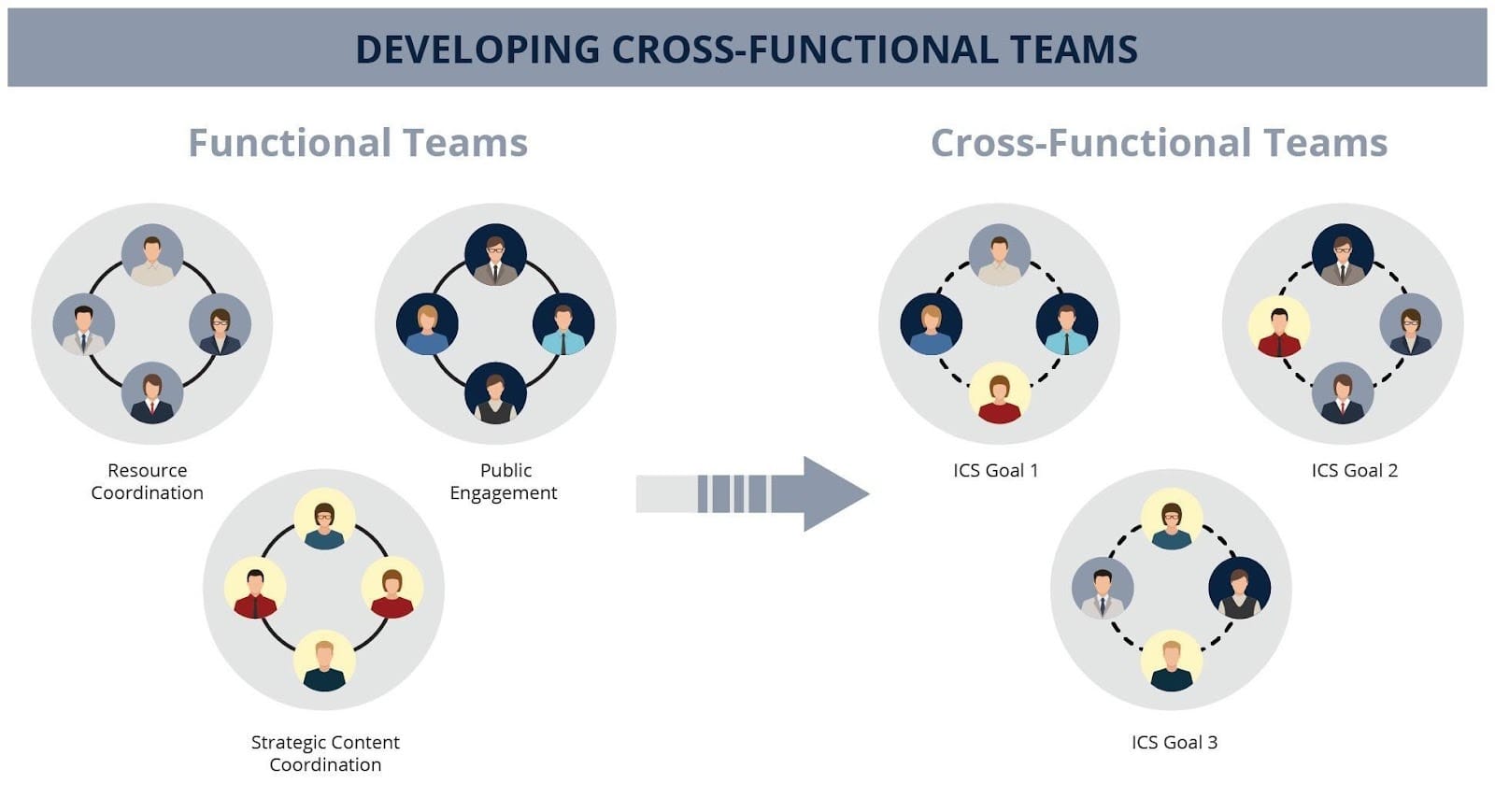

Most projects rely on input from many people with a variety of types of experience and expertise, and there is a paradigm shift afoot in public diplomacy from a siloed team model (with linear reporting structures) to one comprising cross-functional teams in matrixed organizations (where teams report to multiple leaders based on department and project assignments, which may change over time). Cross-functional teams can be described as “a small collection of individuals from diverse functional specializations within the organization” and are critical to achieving team goals. The expectation for collaboration across units is not always explicitly outlined in organizational line charts or position descriptions. Managers must promote cohesion and be exceedingly clear about the expectation for cross-team coordination, with all members working toward a common goal.

Figure 10. Developing cross-functional teams

Establishing norms and processes can encourage team members to collaborate and help leaders identify seams and gaps in a teaming approach. To maximize effectiveness and efficiency, it’s important to build a climate of trust among team members and adopt a unified vision. Leaders build this trust and vision by purposefully and intentionally articulating goals, roles, and processes; by sharing information; and by managing interpersonal relationships.

Silos are reinforced when organizational structures impede collaboration and work across units. Because individuals may have different perspectives or associations, they may feel uncomfortable collaborating with unfamiliar fields. A subconscious “us versus them” mentality can permeate interactions with other team members from different areas. If possible, switch up the membership of cross-functional teams to break down potential overidentification with a single group. The tendency to create unnecessary competition can be mitigated by offering reminders of the common goals of promoting cohesion and efficiency. Resource constraints can also contribute to the formation of silos. Collaborating initially takes more time and planning than conducting solo efforts. If staff feel they don’t have the time needed to complete a task, they will be less motivated to make the effort to collaborate cross-functionally.

Working in cross-functional teams is not easy, but it pays dividends in organizational effectiveness and in achieving the team’s mission. Leaders can proactively foster collaboration by engaging in the actions described below.

- Establish planning teams. For each sub-objective priority or initiative, establish a planning team staffed with a representative from relevant and diverse public diplomacy functional lines. Teams should consider including the Strategic Content Coordination Specialist (SCCS) and Strategic Public Engagement Specialist (SPEC) who has contact with press and media, emerging voices, and established opinion leaders, will ensure you are hearing perspectives from a diverse population. Tailoring working group membership is an ongoing process. Designate a leader to chair the planning team based primarily on expertise and workload, not necessarily on seniority.

- Collect input. Input from all functional areas is crucial, as each area is equipped to discuss factors related to their expertise that impact outcomes. No sub-objective, or key audience, belongs exclusively to one function; all aspects must be considered to properly access the intended population.

- Orient toward the practical. The planning team constitutes the core group focused on an initiative, but others may be brought in at any time. For example, if digital/social media activities are achieving results, you may want to add the community manager or digital production coordinator to the planning team if you plan to expand efforts. Conversely, if digital/social media activities are not resonating, you may want to let the community manager leave the working group to focus on other initiatives and replace them with additional public engagement staff.

- Develop a working hypothesis. Teams develop a hypothesis about how to engage identified priority audiences to reach policy goals, maintaining flexibility to alter methods as needed.

- Report back. Working group members may return to their functional areas to discuss with other team members and reconvene to refine the strategy. Senior specialists in the functional areas are critical sounding boards, resources, and coaches for their team members on sub-objectives projects. Strategic Content Coordination Specialists (SCCS) and Strategic Public Engagement Specialists (SPES) can also be great mentors.

- Report up. Submit the plan to the public diplomacy officer (PDO), and as appropriate to the PAO and others in the leadership chain.

- Refine. Planning teams may need to reconvene to refine the plan if it is not approved by leadership.

- Check in. After establishing an agreed-upon approach, members maintain contact as they return to their sub-unit and continue their work.

- Iterate and adapt. The initial approach may not be properly reaching the intended audience, or it may not be influential, or the influence may work as planned but be ineffective in advancing the policy goal. In any of these cases, reevaluating and adjusting team focus is crucial.

- Check in again. After establishing an agreed-upon approach, members maintain contact as they return to their sub-unit and continue their work.

- Form and re-form planning teams. Planning teams form and disband around particular mission goals as necessary and re-form around other planning goals and initiatives.

Leaders can facilitate work in cross-functional teams by promoting communication, coordination, and cooperation, and by clearly articulating a shared goal. Working across formal management lines makes communication and norms vital. Each team member should trust their colleagues but still feel comfortable raising questions and concerns. Every member of a cross-functional team should be clear about the overall goal of the project, as well as about their own individual duties. Create a collaborative list of responsibilities and divide tasks among the most qualified team members available. Understand that time allocation may vary among team members, as each will be involved in their own separate projects. Functionally, standardizing procedures across the team will make work more efficient and more easily shared.

C. Project management

Project management involves seeing initiatives and activities from the design and planning phases through to execution and completion. The objective of project management is to complete an activity in a given time, to a specified standard, using the allocated resources. The scope and complexity of project management requirements depend on the nature of the initiative, activity, or tasks. A project plan, or project charter, should articulate the project goals, justification, scope, stakeholders, and key deliverables. The PAO or office director is responsible for ensuring that initiatives, activities, and tasks are implemented and managed appropriately by qualified personnel.

Different managers approach projects differently, but in general, project management encompasses five elements: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring, and closing (or maintenance).

- Initiation establishes the scope and nature of a project. It should lead to a broad understanding of why the project is necessary, what it aims to accomplish, how long it will take, and the resources it will require, and it can include analysis of finances, risks, stakeholders, etc. In the PD context, project initiation should be informed by higher-order strategic plans and audience analysis. Project initiation generally produces a project plan or charter that details the findings and results of the initiation stage.

- Planning builds on initiation and adds detail that makes the work done during that stage actionable. Planning lays out in greater detail specific resource requirements, staffing, timelines, and deliverables. Logic models and project plans are an effective way to document planning, by articulating an initiative hypothesis, planning an initiative, and serving as a guide for M&E. Planning also ensures that a system of tools for project management is in place and understood, and it identifies and describes the project management methodology and the expected outputs and outcomes to monitor during implementation. The objective of planning is to prepare for execution.

- Project execution involves putting plans into action to accomplish project goals. During execution, project managers oversee the work of their project team to ensure that resources are properly allocated, work is being carried out, and tasks are being accomplished. Execution concludes when all project deliverables are met.

- Monitoring happens concurrently with execution. Project managers should collect information to:

- Understand the current state of the project and its progress toward meeting its deliverables;

- Track variables to ensure alignment with the project plan; and

- Identify problems or issues that require action by management.

Monitoring may necessitate revisions to planning documentation to account for incorrect assumptions, changing requirements, or new realities that affect implementation.

- Closing is the final stage of project management. It involves the acceptance of project deliverables and the completion of any documentation required by project planning. Closing is the time to identify lessons learned and to document anything that could be useful for future projects. Sometimes, projects may not formally close; instead, they may continue on after execution has concluded. In these cases, closing is better understood as “maintenance.”

There are numerous project management methodologies and tools that are used by both the government and the private sector, and both are applicable in public diplomacy. Two of the most popular are the Waterfall methodology and the Agile approach, both of which have their roots in software development. Waterfall is a more rigid structure that emphasizes detailed planning and a firm timetable for deliverables. Agile is more adaptive, focusing on short-term deliverables and responding to change. A Waterfall approach might be used in planning programs or events on a defined timeline and budget, while an Agile approach might be used by a team working to design a social media campaign that is rapidly changing to respond to real-world events and rapidly-emerging analytics.

What is the relationship between PDIPs and project management?

Project management plays a crucial role in the execution of PDIPs. PDIPs offer a good sense of prioritized initiatives, and completing project management documentation (e.g. project plans/charters, logic models, project closeout, etc.) for important activities that are part of the PDIP will help keep things organized and on track. A project management framework can help to break down complex initiatives and activities into actionable steps and timelines. It can promote transparency and keep everyone informed, ensuring alignment and collaborative success. It can also aid in the effective use of often limited resources. In essence, project management methods enhance the operational effectiveness and strategic impact of PDIPs by promoting careful planning, resource optimization, adaptability, and accountability.

D. How to run effective meetings

Why are effective meetings important?

Effective meetings are crucial because they ensure clear communication, foster collaboration, and drive timely decision making, ultimately enhancing productivity and achieving organizational goals. It is important to develop meetings in thoughtful and deliberate ways to make them beneficial for meeting attendees. Meeting efficiency will not only help you to get the results that you want, but also will show your colleagues that productive meetings are a valuable way to work together. There are many different types of meetings that can meet the needs of the desired goals. While the templates may vary, basic principles outlined in the three steps below can be applied to all situations.

Step 1 - Plan the meeting

Planning the meeting is just as important as running the meeting itself. In fact, planning the meeting will help you run the meeting more effectively. It’s crucial to keep in mind the purpose, agenda, and logistics as you plan the meeting. Some key elements of the planning process include:

- Determine the meeting’s main goals and objectives.

- Identify the desired and required attendees.

- Assign meeting roles and responsibilities.

- Meeting facilitator: develops the meeting’s agenda, sends out the calendar invite, and collaborates closely with the stakeholders.

- Stakeholders: these are usually the project manager/project sponsor/subject matter experts/team members who collaborate with the meeting facilitator to ensure that the agenda meets desired goals and focuses on the project’s progress.

- Notetaker/timekeeper: captures notes from the meeting in the agenda and keeps the meeting timing on track.

- Decision maker: in decision-making meetings, be very clear as to who has the authority to make decisions.

- Decide on a day and time for the meeting.

- Determine where to meet, format of meeting (in-person, virtual, or hybrid), and set up the physical and/or virtual meeting space.

- Ask meeting attendees for agenda items and create an agenda.

- Send out a calendar invite with all necessary information for meeting attendees to participate.

Step 2 - Conduct the meeting

Once the meeting is planned, it is time to meet. Remember the three important R’s in an effective meeting – respect, relate, record. The tips below will help in conducting the meeting:

- Set meeting norms and ground rules.

- Respect attendees’ time.

- Use time markers on the agenda to guide the duration of the conversation.

- During introductions, record the name and office of each attendee.

- The facilitator should help guide the conversation, ensuring equity and inclusion.

- Take notes and distribute them for reference and recordkeeping.

- Assign clear action items and deadlines, and review them before the meeting ends.

Step 3 - Meeting troubleshooting

As much as you prepare for a meeting, being aware of meeting challenges ahead of time will help you to respond in real time with solutions. Here are some examples:

- Have a backup plan, including technology and attendee absences.

- Stay on topic and on time by creating a “parking lot” to capture good ideas and questions, but are outside of the scope of the meeting. Be respectful of attendees’ time by following the agenda.

- Recognize contributions by valuing attendees’ participation and engaging in active listening.

Step 4 - Follow-up

After the meeting, it is important to follow-up and continue to engage with attendees. Here are some basic best practices:

- Thank meeting participants for their time, effort, and participation and for the follow-up work they’re going to do.

- Share the meeting notes with all attendees and ask for any additions, revisions, clarifications, or questions.

- Follow-up on assigned tasks, deadlines, unanswered questions, or touchpoints.

- Schedule any additional meetings decided on during the meeting.

Meetings are more effective for hosts and attendees when the three-step method outlined above is used. Deliberate planning, implementation, and follow-up phases may involve more thinking initially, but become routine over time. When all members of a team understand the importance of focused meeting time, everyone benefits.

E. Change management

Although effective project planning paves the way for success, projects are also affected by human and organizational factors. Leaders who want to create meaningful change and sustain those changes in the long-term must think about and actively manage change in an organization. Change management is a structured approach to leading projects and programs toward a desired and lasting outcome. Every project involves some level of change; by effectively managing those changes, you can position your team for success. There are many models for approaching change management, but John Kotter’s 8-step model offers a simple and actionable process that can be considered for every project.

- Create a sense of urgency: Establish why the change is important and convey that importance.

- Form a powerful coalition: Ensure that you have the right people involved in the change; this includes engaging powerful stakeholders who may block the process, experts who may contribute, partner groups that may increase your credibility or resources, and the right managers to implement.

- Create a vision for the change: Build a clear vision of what success will look like and of the impact it will have.

- Communicate the vision: Create buy-in and remove potential barriers to implementation by communicating the vision for change at every opportunity.

- Empower action: Leverage your powerful coalition to identify and remove barriers to the change.

- Generate short-term wins: Set short-term goals to achieve and celebrate to generate a sense of momentum for the change and gain ongoing support from your stakeholders.

- Build on the change: Use the short-term wins as opportunities to reflect on how things are going, engage your stakeholders, and eliminate more barriers to implementation.

- Make it stick: Discuss the importance of the change and lessons learned, and ensure that these lessons roll forward into future projects.

F. Knowledge management

Effective public diplomacy requires sophisticated, multifaceted, and unique engagement strategy with host country audiences. The scope of work for PD personnel ranges from extensive research, building and maintaining relations with local figures and organizations, to operating a plethora of projects and programs, and more. Considering this immense breadth of duties, including the vital administrative day-to-day demands of any high-functioning organization, every PD section employee serves an essential function and is a valuable resource. The unique experience, values, contextual information, and insight that one cultivates in their role, from local relationships and regional expertise to strong familiarity with section routines, processes, practices, and norms, makes their knowledge not easily replaceable. This, however, may become a hindrance if an employee with unique knowledge departs from their position. When knowledge is not easily accessible, it can be incredibly costly for a busy PD section to spend valuable time finding information instead of having it readily available and usable for the person who needs it.

Maintaining a carefully recorded knowledge base of data, information, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and much more, can be a valuable asset for a PD section. Consider, for example, an easily accessible repository of operational knowledge, such as local sources, previously crafted content, and an organized list of resources, that would make onboarding and familiarizing a new PD officer to post significantly easier. Well-kept filings of specific subject-matter knowledge, such as precise and up-to-date analyses of local trends, public opinion shifts, and policy developments, can enhance the development of long-term strategic planning. Maintaining and developing such a breadth of information in an organized fashion may initially appear daunting, but practicing effective knowledge management principles systematizes and simplifies the process.

Knowledge management is the process of creating, capturing, storing, sharing, and utilizing knowledge within an organization to improve efficiency, innovation, and decision making. It involves identifying valuable knowledge assets, such as data, documents, databases, expertise, and tacit knowledge (i.e., knowledge that is not easily codified), and implementing strategies to leverage these assets effectively. Basic components of creating a knowledge management system within a PD section include:

Create knowledge: Encourage the generation of new knowledge through research, development, and innovation, understanding what knowledge is critical for your organization's success. You generate knowledge about your projects, programs, and decisions every time you do them, and all of this knowledge can inform future decisions, but only if it is available for use in the future.

Capturing knowledge: Once knowledge is created, it must be identified, collected and captured as knowledge – that is, you have to identify something as important enough to capture it before it can be integrated into your organization’s knowledge management system. Knowledge may be captured in a document, photograph, artifact, email, or other type of record. Establishing regular and systematic procedures for creating knowledge capture will provide a steady stream of insights that you can use to inform future decisions.

Store and organize knowledge: Once you’ve captured knowledge, storing it consistently and making it easily accessible by organizing it transparently is essential. Captured knowledge can be organized and stored in accessible repositories, such as databases, intranets, and knowledge bases. Part of the task of storage and organization in knowledge management may include creating a consistent file naming convention to help people locate records. Additionally, you will want to ensure that records (captured knowledge) are stored in accessible locations; for example, do not file documents in personal folders or drives, as this hinders accessibility and sharing.

Share knowledge: A key corollary to accessibility is sharing and collaboration to aid in the distribution and dissemination of knowledge throughout an organization. Knowledge can be useful only if it is actually shared and known. In addition to being accessible, people must know they can find it. You can facilitate the sharing and distribution of knowledge among employees and stakeholders (as needed) through collaboration tools, training programs, communities of practice, and other communication channels. You can improve the practice of PD as a whole by developing a robust network of lessons learned and best practices. Check out the PD@State Share Best Practices and Lessons Learned page for additional guidance on effectively capturing, storing, and sharing your best practices and lessons learned.

Utilize knowledge: Even when knowledge is appropriately stored, organized, and shared, it still must be used to achieve its highest purpose. Applying knowledge to solve problems, make decisions, improve processes, and innovate within the organization are hallmarks of learning organizations and of organizations that will experience organizational growth and change. Periodic reviews of knowledge management practices allow the organization to refine and improve systems for generating, capturing, synthesizing, and sharing institutional knowledge. These reviews help identify gaps, eliminate redundancies, and ensure that knowledge flows seamlessly across departments, empowering teams to build on past successes and learn from past challenges.

Addressing a common pain point: transfer season

While following sound knowledge management processes supports knowledge transfer across teams and individuals, sections still may struggle to preserve institutional knowledge when employees leave the section and new ones arrive. Employee turnover is common in all organizations, but it is especially frequent in the State Department, where all American foreign service officers rotate jobs on a predictable 2-3 year cycle. While high turnover is a challenge, its predictability also offers some advantages to sections in allowing them to prepare for routine knowledge transfer. Several offices within the Department offer helpful resources with guidelines for setting up an effective knowledge-sharing process when employees prepare for departure. “DT’s Best IT Knowledge Practices for a Smooth Transition during Transfer Season” outlines the “different types” of knowledge, to streamline figuring out “what” to share while also providing recommendations on where to share, including online cloud-based repositories like Sharepoint and OneDrive. PD Section Handover Tips, produced by R/PPR, and the PD Officer Transition Plan (Appendix H) both offer an in-depth checklist and guide for outgoing PAOs to fill out and provide to incoming officers. Using these resources and promoting a culture of knowledge sharing will make for smooth transitions and improve both morale and efficiency.

It is also important for LE staff to prepare and participate in transfer season knowledge transfer. LE staff provide deep institutional knowledge about PD section operations, procedures, local culture, historical projects, ongoing initiatives and activities, and have the ability to provide context to issues that might be difficult in handover notes. LE staff also ensure continuity of daily operations and can help familiarize incoming officers. LE staff also can introduce incoming officers to key contacts and help them build a network faster and more efficiently to maintain strong diplomatic ties. They can impart knowledge on local security risks, political dynamics, and a myriad of other issues. A proactive transition process benefits both incoming officers and the mission as a whole, maintaining strong workflows and enhancing effectiveness.

G. Budgeting and financial management

Managing financial resources and effectively navigating budget processes is essential for success in a PD section, but it can be the source of stress and anxiety for people who are not budget experts. This section outlines some of the basic principles for budgeting and financial management for PD work.

1. PD funding sources

Public diplomacy at overseas posts is carried out with financial resources from a variety of streams, each of which has different rules that guide and regulate their use. Some of the most common funding streams are defined here.

Diplomatic Program Public Diplomacy funding is often referred to as .7 funding. This money is allocated to posts for supporting costs for activities directly expensed against the PD appropriation.

To execute PD interventions and programs, PD staff may use several sources of funding in addition to the Diplomatic Program (.7) funds. Money from these sources is distributed differently and comes with unique statutory or regulatory requirements governing its use. The PD Funding Matrix provides relevant details on the uses of .7 funds vs. ECE, which are the two most commonly used sources of funding. These various funds often have unique reporting requirements as well, and these should be understood and considered from the beginning of the planning process. PAOs should consult with their financial management officer (FMO) to ensure funds are spent appropriately. PAOs should understand what money is available to support their mission’s strategic priorities and how to avail themselves of these funds.

R/PPR and regional offices reserve a portion of their allocations for unfunded requests (UFRs), especially at the end of the fiscal year. PAOs may make requests for special initiatives and for emerging or unplanned needs, such as requests for severance payments not covered by the Foreign Service National Separation Liability Trust Fund. The RPPR/front office and the regional office director respectively hold the authority to approve or deny submitted UFRs.

2. Budget formulation process

Understanding the basic philosophies and processes of the federal budget at a macro level will help PD sections in their budgeting and resource allocation tasks at a local level. Budgeting and planning timelines can be long, but they are also predictable. Just as strategic guidance is nested from the NSS to the ICS, budget requests are also nested.

The President’s Request is a statement of Administration policy, and the Department of State and USAID have input into this request. Decisions are made at various stages before reaching the final document, which is influenced by both internal stakeholders in the Department, including the regional and functional bureaus, the Bureau of Budget and Planning (BP), and the Enterprise Governing Board (EGB), as well as external stakeholders like the OMB. Importantly, if a request made in year one is not approved and the need persists, PD sections should continue to make the request. It can take several annual budget cycles before a need is recognized and results in a base increase to funding.

For overseas posts, the Mission Resource Request (MRR) is the first step, and an important step, in the State and USAID budget formulation process. PD sections should use the MRR to describe the resources required to advance the nation’s foreign policy goals and make progress on their mission objectives, outlined in the ICS, and to delineate how those objectives roll up to the bureau objectives articulated in their respective FBS or JRS. The MRR develops the funding request two fiscal years into the future (FY+2). PD sections should use the MRR process as an opportunity to advocate for the resources post needs to advance projected mission goals and priorities.

From there, bureau leadership develops the Bureau Resource Request (BRR), which references narratives and requests for additional resources contained in the MRR submitted by each post in the region. If the PD section identifies a need to request a programmatic or staffing increase, it should include a justification in the MRR that articulates how the increase will better position the PD section to achieve the bureau’s strategic goals and objectives as articulated in the FBS or JRS. These requests will be evaluated and potentially included in the BRR. Bureau leadership submits the BRR to the Bureau of Budget and Planning (BP).

3. Considerations for budget planning

At the beginning of the process, ideally early in the fiscal year, every PD section receives a budget target from its regional bureau. The budget target represents the regional bureau’s calculation of post’s base requirements for .7 funds for the coming fiscal year. This calculation is based primarily on prior year fiscal data from each post. Budget targets represent the total amount of funding a section will receive in the coming year. They should be used as a starting point for planning an annual budget.

Based on the budget target provided by its regional bureau, PD sections should plan an annual budget as they complete the PDIP process. This is generally done by the PAO in conjunction with the post Financial Management Officer (FMO). Budget resources are expended to support section activities, but PD teams should relate their budget priorities to their strategic priorities and include budget allocation at the initiative level.

The first item to consider, mandatory costs, which are calculated by the FMO and budget staff, are deducted from the target. Mandatory costs always include LE staff salaries and benefits. These costs vary significantly from post to post but should generally not exceed 75 percent of the target. Other mandatory costs may include internet or phone service and other recurring expenses.

Once mandatory costs have been calculated, the remaining funds are available for non-mandatory expenses, such as translation contracts, subscriptions, training, travel, or new equipment. These costs may vary from post to post and from year to year, but it is often good practice to set these at a baseline percentage of the target budget. Additionally, PAOs should designate some money for audience research, for M&E, and for emerging issues. The Department’s grant and contract regulations allow performance M&E as program or project costs. The guidance in 18 FAM 300 provides methodologies for determining program funds to be set aside for M&E during budget formulation.

After all of these expenditures are accounted for, a PAO and their team are left with a programming and grant-making budget. In reality, this number may be a small fraction of the total budget. This is where thinking strategically comes in. What priorities are most important? What programs can start in an unfunded category and be executed on short notice if funds become available? How can the post best allocate scarce resources to achieve impact? How will existing contracts and relationships play into budgeting decisions? How can different parts of the PD section or the mission work together to achieve efficiencies and make progress toward goals? What are opportunities for collaboration and teaming across mission priorities?

All planned activities should have a notional budget, and spending should be prioritized according to the relative strategic importance of each activity. Given uncertainty around disbursements throughout the year, it is good practice to plan unfunded programs that can be quickly operationalized if more money than expected becomes available.

4. Financial management

The PAO is ultimately responsible for managing PD financial resources, including the oversight of funds awarded through grants/federal assistance that are initiated at post. The PAO may assign daily responsibility for program/resource management and the handling of financial requests to another USDH and/or LE Staff member. PD staff must work closely with their financial management office to ensure good management and adequate controls over spending. The FMO’s accounts are the official record of a post’s financial situation. PD section staff should request regular budget reports on a regular basis or as needed.

Still, it is advisable for PD leadership to maintain an unofficial record of expenses in a spreadsheet or elsewhere to track program funding. This is often called a “cuff record” or an “abacus.” These records serve as a close estimate of a PD section budget at any given time, and they should be reconciled regularly with FMO reports.

Federal assistance awards (including grants and cooperative agreements) play an important role in PD programs. PAOs and/or their designees are responsible for executing, monitoring, and evaluating grants that are generated at post. Posts may generate grants or cooperative agreements using PD funds to collaborate with in-country or U.S. organizations on projects. Federal assistance awards using PD funds may be used only for PD purposes. These awards are administered by the PD section for programs that are intrinsically focused on engaging with the public and that connect, inform, inspire change, or persuade priority audiences regarding mission-level strategic goals and objectives.