PD In Practice: Section III - Detailed Planning with Logic Models

A. Introduction

Planning is crucial to the successful implementation of PD initiatives and activities, and it is a key responsibility of all PD practitioners. Planning exists on a continuum. When a PD section or PD team has engaged in a strategic planning process, it will have identified the initiatives that contribute to achieving a specific U.S. foreign policy objective. This guidance encourages practitioners to use the design approach for public diplomacy, outlined in the previous chapter, as the primary strategic planning model to identify policy goals, PD outcomes, priority audiences, and key initiatives, and then to use a variety of detailed planning approaches and models to move from ideas to application. Detailed planning is preparation for tactical action that supports the attainment of strategic goals and objectives. As the PD section moves from strategic to detailed planning, PD practitioners start to put specifics in place, especially around implementing, managing, and monitoring initiatives and section activities.

Planning takes devoted time and resources, and doing it well facilitates implementing, managing, and monitoring PD initiatives and activities. Planning supports the attainment of strategic goals by continuing the task of linking tactical actions to strategic objectives by:

- Ensuring appropriate resource allocation;

- Continuing to refine audience analysis by understanding the demographic, geographic, and other characteristics of the groups you consider for outreach;

- Supporting audience segmentation (i.e., the ability to identify narrow audience sub-groups by factors such as gender, age, or geographic location, which can be aided by leveraging data from Department tools like CRM or social media platforms); and

- Laying the groundwork for monitoring and evaluation.

Detailed planning focuses on initiatives and activities that contribute to achieving but do not themselves accomplish strategic-level objectives. Planning, in this context, focuses on immediately attainable objectives, specific resource needs, and direct actions or tasks that achieve outputs and/or short-term outcomes.

Keep in mind that detailed planning involves both initiatives and activities. An initiative is a campaign or group of activities intended to achieve an objective or sub-objective. Initiatives are the major building blocks of a mission or section’s PDIP, as they link sets of activities, programs, and messages to a foreign policy outcome. An activity is a program or project action undertaken to achieve a targeted outcome that contributes to the broader outcomes defined in the parent initiative.

Why detailed planning matters

- The planning process helps ensure that programming aligns with higher-order priorities and directly supports the foreign policy and national security objectives of the United States. Detailed plans should articulate clearly the cause and effect relationships that link activities and initiatives to the relevant ICS sub-objective.

- Planning describes success in detail and establishes indicators and metrics to measure an initiative or activity’s progress toward achieving its objectives. Detailed planning records can be used by future PD professionals, ensuring an organization can learn and adapt.

- Detailed planning that is documented in a systematic and logical manner promotes operational capacity. Plans should be fully articulated, documented, and stored in an accessible way, so they can be delegated to other practitioners as needed. Planning informs leadership of program and resource needs and facilitates better leadership buy-in, which helps to limit extraneous requests, or at least to acknowledge the trade-offs involved. Good planning also creates a documentary record that keeps leaders apprised of a section’s activities and enables them to request and allocate resources appropriately.

- Planning generates buy-in and involves assigning roles and responsibilities to team members who are ultimately responsible for ensuring that the plan is implemented efficiently and cooperatively.

- Planning also provides space for the team to develop a strategy to address possible obstacles to implementing the plan fully.

The typical stages of detailed planning

- Determine the nature and scope of the initiatives that have been identified through the strategic planning process.

- Conduct detailed audience research and analysis to identify priority audience segments, including the beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes that a PD initiative will aim to change, and the characteristics (demographic, psychographic, etc.) that are relevant to identifying and changing those attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

- Write an initiative or activity objective.

- Fill in a logic model to outline the required inputs, audience, and activities as well as the outputs and outcomes (short- and long-term) and assumptions for the initiative or activity.

- Use the completed logic model to develop an initiative hypothesis about how the initiative or activity will achieve its objectives.

- Follow the guidance in the PD Monitoring Toolkit to determine outcomes, and to develop monitoring plans for section activities that require monitoring.

- Allocate human and financial resources to the initiative or activity and estimate costs for completion.

- Write action plans and delegate tasks for execution at the activity level.

A single initiative is unlikely to address all the component parts of a sub-objective-level problem, which is why advancing the ICS sub-objectives may require the development of several initiatives. Initiatives may be designed to address all or part of a sub-objective problem statement. PD initiatives should focus on the aspects of the broader problem that their sections or offices are best resourced and positioned to address.

This section walks you through the process of planning (and creating a record of) a PD initiative. Initiatives are groupings of coordinated PD activities that together advance a specific portion of an ICS sub-objective. Once a PD section has identified the need for a PD initiative (as part of developing a PD approach to a sub-objective), planners will conduct a more detailed audience analysis, establish an initiative objective, develop a logic model for the initiative, write an initiative hypothesis, and begin to design activities that fall under the initiative. These steps are explained in more detail below. These steps are also applicable at the section activity level, although not all steps are necessarily required for reporting.

B. Planning with monitoring and evaluation in mind

By undertaking detailed planning to achieve specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound objectives, your team will enable and support the Learn and Adapt element of the PD Framework, which relies on principles of monitoring and evaluation (M&E). Although specific guidance on M&E is covered in Section V, Assessing, Learning, and Adapting, some key questions and considerations are introduced here to reinforce the relationship. If you follow the planning steps outlined in this document, you will be well on your way to being able to create effective monitoring plans for your section’s most important PD programs. Question 1 is covered in the Section II: Strategic Planning, and questions 2-4 are covered in this section on Detailed Planning.

- What is your ICS Objective? Which goal outlined in your PDIP or ICS mission-level objective does your proposed program address?

- What is your initiative objective(s)? Each initiative should have a specific objective that can guide what methods and variables you choose to monitor or evaluate your PD programs. An initiative objective should articulate clearly what you want, including outcomes your program is designed to achieve.

- What is the initiative hypothesis or theory statement? A hypothesis (or theory statement) explains how your proposed project activities will result in the desired initiative outcomes and objective. It explains the cause-and-effect relationship between what people are doing and the expected response; whenever possible, focus the hypothesis on the audience, rather than on the U.S. actors. Why do you think the initiative will produce the desired results?

- What are your indicators of success? Indicators allow you to track progress toward an objective over time. An indicator is a data point or measurement that tells you whether you are making progress toward your desired end-state. They can track either outputs or outcomes, can be qualitative or quantitative, and are neutral data points. A good indicator allows you to track progress toward your objective over time.

C. Writing an initiative objective

In addition to giving your initiative a title and a description, at this stage, it’s also best to write the initiative objective(s).

A clear initiative objective describes the results you want to achieve with the selected priority audience. It will give the initiative (and the staff who are working on it) a clear vision and direction, which will help guide the section’s decisions. The initiative objective should be written as a SMART objective and focus on outcomes (e.g., changing attitudes) rather than outputs (e.g., number of people trained). The mnemonic device “SMART” is often used to describe attributes of goals, objectives, outcomes, and indicators. SMART stands for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and timebound. See Appendix E: Planning tools on using SMART criteria to write objectives.

An initiative objective will have the following components:

- The outcome to be achieved – that is, what do you want people to know, feel, or do?

- The direction of the desired result – that is, do you want the desired outcome to increase, stay the same, or decrease?

- The magnitude of the desired change – that is, how much or how intensely should the belief, attitude, or behavior change?

- The timeline for achieving the objective – that is, when should the initiative achieve its results?

Examples of initiative objectives:

- Related to “raising awareness:” Within three months of launching the initiative, the number of surveyed high-school participants who know about study-abroad opportunities in the United States will increase from 20 percent to 30 percent.

- Related to “affecting attitudes:” By the end of the third quarter, the number of focus-group participants who see Zubrovka as their country’s preferred strategic partner will be reduced by one-third.

- Related to “skills building:” By December, 50 percent of the entrepreneurs who participate in one or more of our initiative activities will have a written business plan that can be shared with microlenders and other investors.

D. The logic model

What is a logic model?

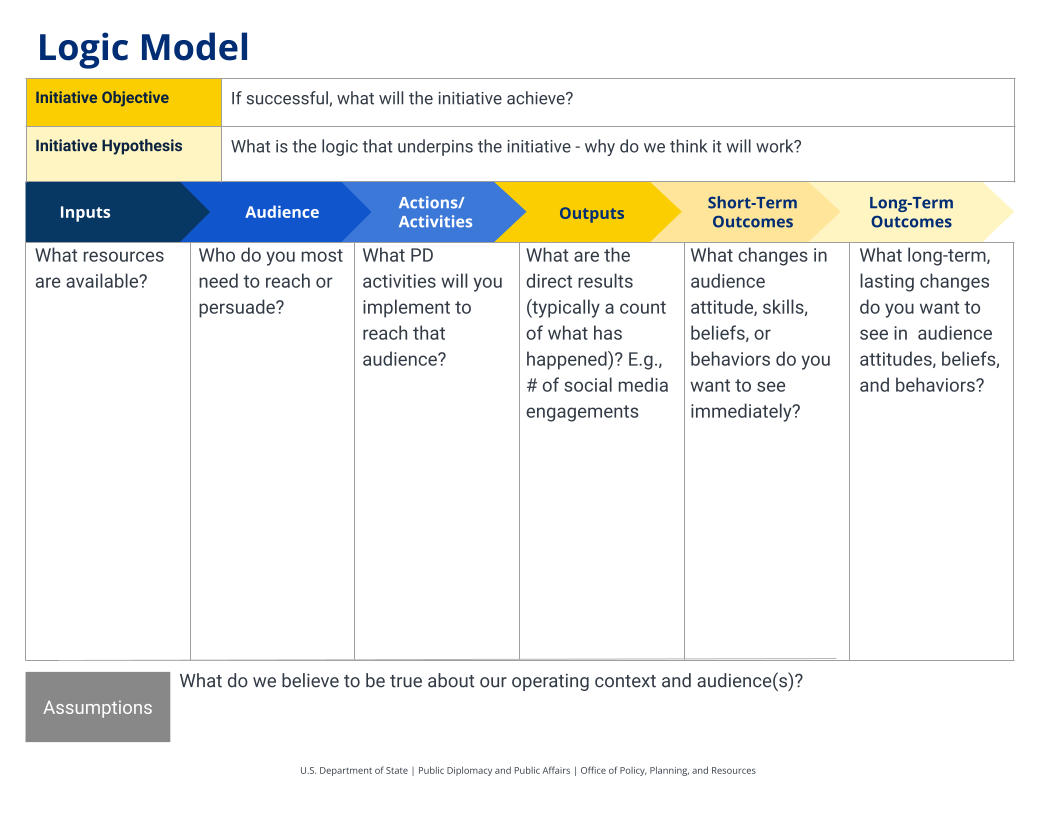

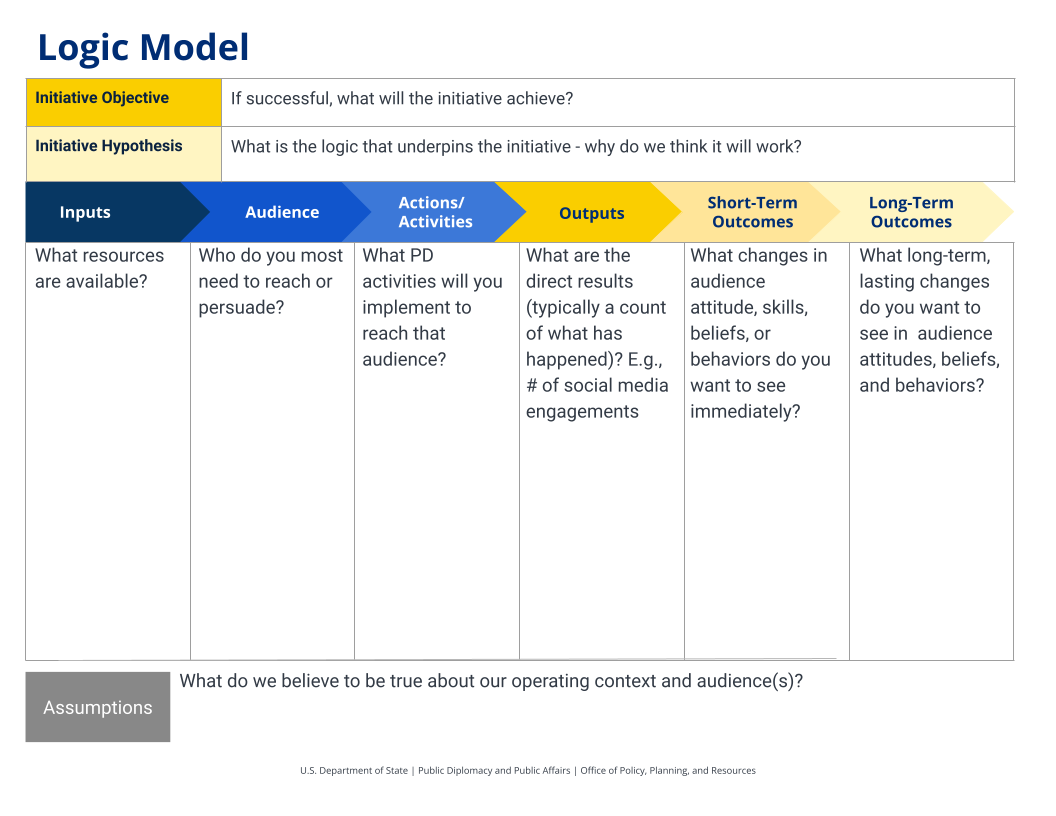

Logic models are visual guides that outline how section activities will lead to expected changes in priority audience groups, ultimately achieving a defined objective or goal. Similar to a math equation or recipe, a logic model ensures balance between what goes in on one side and what comes out on the other. In the context of public diplomacy, the logic model combines inputs (resources), audiences, and actions to produce outputs and short-term and long-term outcomes. The logic model serves as a template for "if-then" thinking, helping to articulate the relationship between actions and desired results. This relationship is typically presented in a table format, like the one below:

Figure 8. Logic Model Template

Why complete a logic model?

Logic models are useful tools for several reasons:

- Logic models establish a common reference point for PD practitioners on how section activities will work, including important “if-then” relationships between section activity elements. They are a useful, high-level guide to ensure everyone on a team understands the big picture and keeps objectives front and center during the project’s roll-out.

- Logic models underpin key elements of monitoring plans. The content outlined in logic models informs what monitoring data to collect about section activities. In situations where an evaluation is appropriate, a logic model’s articulation of an initiative/section activity’s “how and why” helps evaluation teams to identify areas to investigate.

- Logic models help ensure the alignment of resources, actions and results and add clarity to planning by asking teams to refine their objectives, hypotheses, and assumptions.

- Logic models promote accountability by providing a checklist during implementation to ensure major parts of a section activity are being implemented as intended.

- Logic models enable clear communication with stakeholders by allowing you to tell the story of how a section activity will advance policy goals.

- Logic models can guide assessments and encourage learning. Outlining the major components of an intervention makes it easier to ask and answer questions like, “Did we achieve the outcomes we anticipated?”, “Did we reach our priority audience?”, and “Were our planning assumptions correct?”

When to complete a logic model?

Completing a logic model is part of the detailed planning process.

The logic model is a useful tool to facilitate the detailed planning process. PD sections should complete a logic model for each new or ongoing section activity or initiative the section decides to monitor. To begin this process, PD sections already should have conducted situation analysis, which includes desk research on the relevant topic and local conditions and identifying a priority audience (REFTEL 22 STATE 115522). Additionally, sections already should have created a problem statement that articulates the gap between or challenges faced in moving from the current (observed) environment and the future (desired) environment. With these elements in place, sections are ready to begin detailed planning and complete a logic model.

Who should complete a logic model?

The team directly responsible for implementing the section activity should complete the logic model, whether that is an implementing partner or a project lead within the PD section.

The section activity lead is encouraged to consult with a diverse group of stakeholders to draft the logic model to:

(1) establish strong logical relationships (i.e., between inputs, audiences, activities and outputs, and between outputs and outcomes), and

(2) identify an initiative/activity’s relevant assumptions and external factors.

How to complete a logic model

When creating a logic model, start by discussing and agreeing upon the expected outcomes so you can plan for the other components to lead to the desired long-term results. Then, use the logic model template (also illustrated, above) to record your team’s thinking in a systematic way.

Step 1: Develop short-term and long-term outcomes

Regardless of who directly implements the section activity, PD section leads should identify the expected outcomes aligned with foreign policy priorities during the detailed planning process.

- Outcomes: Outcomes are the effects your efforts should have on your priority audience and align with the initiative or section activity goals.

- Short -term outcomes: Short- term outcomes are those that happen immediately after activities or actions.

For example: A short-term outcome of an entrepreneurship workshop could be that participants develop a marketing strategy. A short-term outcome of a social media campaign may be increased awareness among desired followers of post-implemented events and workshops.

- Long-term outcomes: Long-term outcomes are also effects or results, but they happen in sequence after and often build upon short-term outcomes. A section activity may build awareness in the short term, and this awareness could lead to a long-term outcome of an attitude change. This shift could take three weeks, or it could take three months, or even three years; the sequence is more important than the timeline.

For example: A long-term outcome of the entrepreneurship workshop could be an increase in clients as a result of implementing a marketing strategy. A long-term outcome of the social media campaign could be that followers take action, such as participating in post events and workshops.

Additional guidance on developing outcomes can be found in the Monitoring Toolkit, Appendix E: Developing Outcomes.

Step 2: Develop outputs

- Outputs: Outputs are the direct products or actions that result from the section activity, such as the number of workshops or participants. They are typically tangible and countable. Some common PD outputs are number of participants, number of “likes” on a social media post, or number of workshops held.

Step 3: Brainstorm activities

- Activities: Activities are the tangible actions you will take (e.g., design and release a social media campaign raising awareness on gender based violence) or things you will do to reach your priority audiences and achieve your desired outputs and outcomes. List the activities you are planning to do. If you are writing a logic model for a section activity, you may break the section activity into discrete tasks or steps (e.g., create video for social media, create survey, book venue, book speaker, register participants). If you are writing a logic model for an initiative, you may list the various section activities you will be completing (e.g., social media campaign, curriculum development, workshop series, and a speaker series).

Step 4: Identify your audiences

- Audiences: The section activity audience is the group(s) of people you want to reach and affect through your policy-centered efforts. You should prioritize and segment your audiences before planning specific efforts, so you should have a clear idea of your audience before developing a logic model, and then record that audience in the model. For more guidance on how to identify and segment your audiences, see: Analyze Audiences on PD@State. While many sectors and industries use logic models, the “audience” column is unique to the PD logic model. This column underscores the fact that audiences are central to PD work.

Step 5: Develop a list of inputs

- Inputs: Write the resources invested to start and maintain a section activity. This column’s entries typically include staff time, funding, and facilities. Other inputs may include venue space, curriculum materials, literature, organizational partnerships, equipment, computer software, expertise, a survey, images, graphics, etc.

Step 6: Document assumptions

- Assumptions: Assumptions are things you believe to be true that inform why you believe a section activity will work. Planning assumptions are things that you assume will hold true for your plans to stay on track. For example: if you plan to do a radio campaign, you assume that your target audience owns a radio and listens to the radio. Or you could plan for a speakers’ series in February, based on the speaker’s availability and the country’s major holiday, but plan to shift the event to May if funding is not available in time.

Step 7: Review and refine your logic model

- Review: Finally, look over your entire logic model, and work to refine it to ensure that the connections from one component to the next are simple and clear. Section activities are built on underlying assumptions of cause and effect. Use the logic model to check these assumptions by focusing on the “if-then” relationships within the logic model. Are there any gaps? Are there any areas where you have to rely on a lot of assumptions to proceed from the “if” to the “then”?

Resources for completing logic models

For more information on completing a logic model, please consult the following resources in the PD Monitoring Toolkit:

- Appendix C: Logic model template

- Appendix D: Completed logic model example

- Appendix E: Developing outcomes

E. Initiative hypothesis

In scientific or social scientific inquiry, a hypothesis is an educated guess about the relationship between two or more variables. Articulating the relationship between these variables forces us to explain the connection between them and to uncover our assumptions about this relationship or about the variables themselves. Making these connections is a core element of PD planning.

A hypothesis makes explicit the connection between a PD initiative or activity and the advancement of policy goals. Establishing a hypothesis about why and how a PD initiative or activity will work enables us to test that claim once we have implemented that engagement and to continually learn from and refine our efforts, which also helps to save resources, if we can identify that they should be reallocated to more strategic work.

The initiative hypothesis explains how the design, actions, and implementation of a PD initiative lead to the results you want with your target audience. In simpler terms, it shows a cause-and-effect relationship between what you do and how your audience responds. The stronger and more logical this connection is, the more confident we can be that the PD effort influenced the outcome. By tying the initiative directly to the problem it aims to solve, the hypothesis also shows how the initiative will address the issue and help achieve the desired goal or U.S. foreign policy objective. This logic should guide all decisions in planning and carrying out the PD initiative.

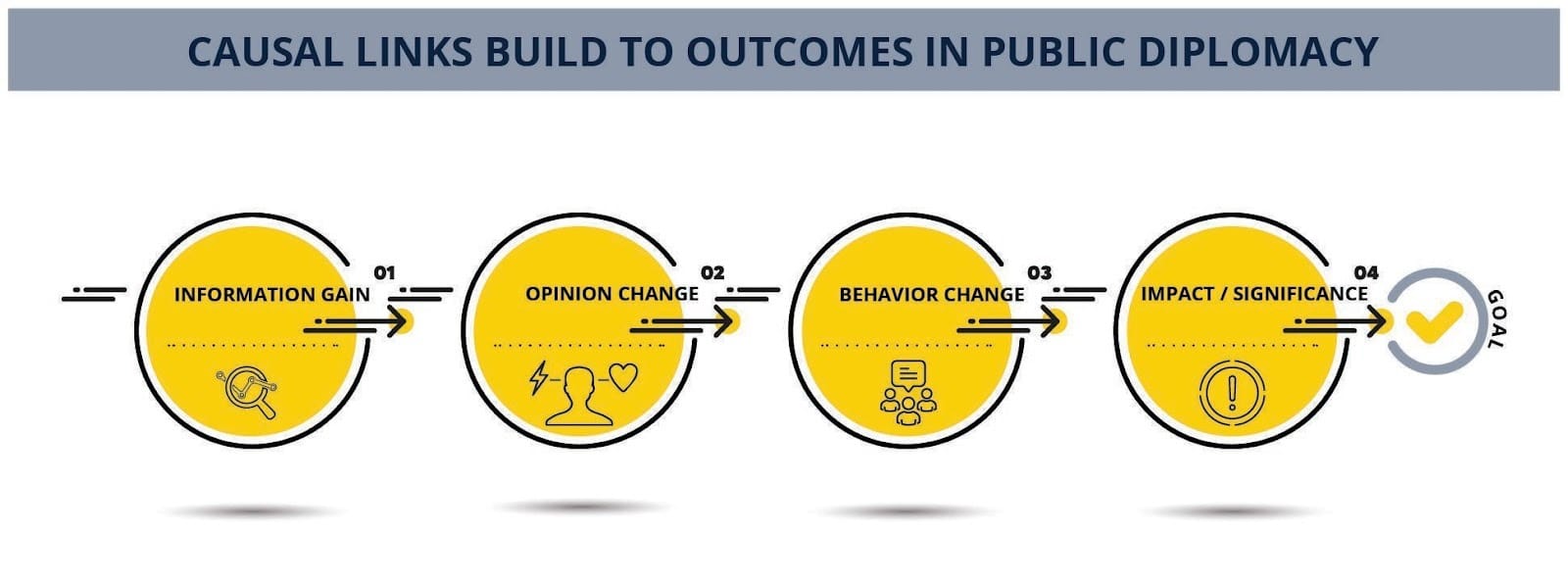

Strong hypotheses point toward specific changes desired in the future state. They also create a causal link between desired changes in audiences and the linked goal. Causal relationships in public relations and public diplomacy work can often be expressed in a chain that looks something like this:

Figure 9. Causal links build to outcomes in public diplomacy

Understanding the relationship between these stages can help PD practitioners articulate the specific attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (and the audiences who exhibit them) that need to be changed or reinforced if PD initiatives and activities are to be successful. Given the complexity of the causal chain and the many factors affecting our audiences, it is unlikely that a single initiative or activity will move an audience through all the steps at once. To change opinion, you may first need to build awareness. To change behaviors, you may first need to persuade an audience to adopt a new attitude. PD initiatives and activities work in incremental ways, over time, to promote change. Being realistic about the changes you might expect to achieve with a single initiative or activity is important. In most cases, an initiative can address only some of the gap between the current state and the desired future state.

Importantly, a hypothesis, whether in scientific inquiry, social scientific research, or the practice of public diplomacy, might not be right. In the end, we might find that the relationship between our variables is not what we expected. Perhaps the evidence to support the claim simply doesn’t exist; perhaps the relationship is the opposite of what we thought it would be; perhaps there were other inputs or variables that complicate or confound the relationship we are trying to observe. None of these is a fatal flaw. In fact, learning from hypotheses that turn out to be unprovable or false is critical to refining and improving future hypotheses so that our efforts are more effective. There is no way PD practitioners will identify every causal relationship at play or correctly estimate the effect of every initiative or activity. However, if we learn from each relationship and effort, continually adapting hypotheses over time, we will greatly improve our craft. A hypothesis statement is an important step in examining these relationships and making a meaningful foreign policy impact through PD engagement.

For PD practitioners, the initiative hypothesis proposes a claim about the relationship among four core inputs:

- the problem statement

- the PD initiative

- the intended audience’s attitude, belief, or behavior

- the result of that attitude, belief, or behavior on the policy issue at hand

Articulating these elements enhances our ability to validate that the work we are doing is reaching key publics and, ultimately, advancing our foreign policy goals through targeted engagement.

Hypothesis statements can take a variety of forms, but they should contain certain essential components. Templates and examples are available in the Initiative Hypothesis Worksheet and Appendix F: Initiative hypothesis templates and examples can help your team focus their efforts and ensure your statement offers a complete explanation of the causal logic at work in your PD efforts. These templates can be modified to fit specific circumstances.